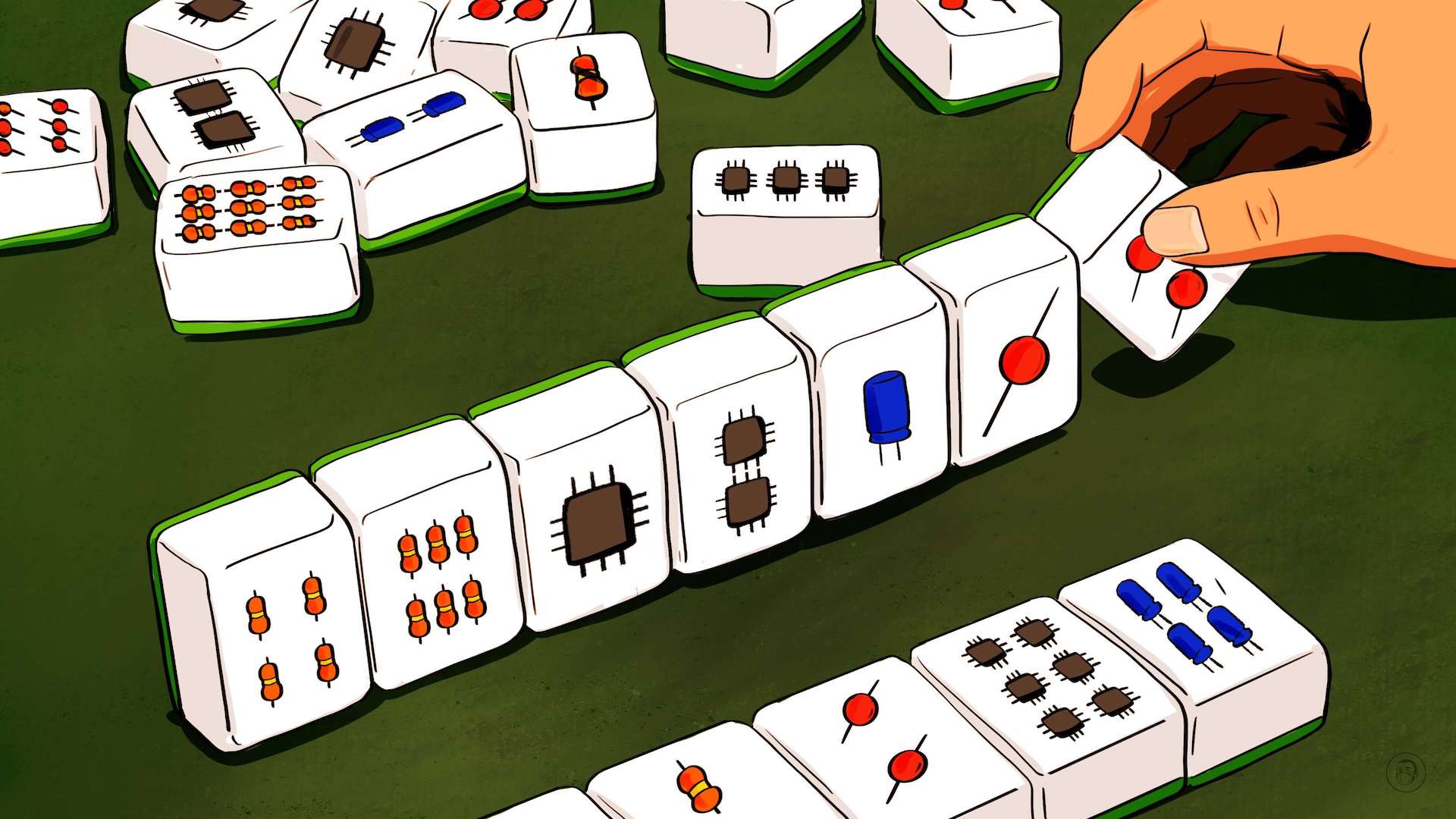

The U.S. deals another blow to China’s chip industry and Beijing reacts with a trillion yuan plan

Globalization is over: Beijing is responding to U.S. restrictions on tech sales to China by juicing the local market, but Chinese chip firms are struggling and global companies are stuck in the crossfire.

The latest round of U.S. export controls on computer chips hit China’s beleaguered semiconductor industry last week. It is not yet clear how Beijing will respond. Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 and his new team of economic planners, along with executives of leading Chinese technology firms all have decisions to make.

“Geopolitical confrontation has distorted the entire market”

The new controls that were dropped in mid-December add to a growing list of measures intended to corral China’s domestic ability to design and manufacture any semiconductor that U.S. officials believe can contribute in some way to China’s military modernization.

The new U.S. approach to technology competition with China was described by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan in September as “small yard high fence,” in other words, limiting the range of technologies that are restricted but making it very, very difficult to get them. But the new U.S. framework has in fact now cast a very wide net both in terms of limits on sales of semiconductors and other technology to Chinese firms, and because a cripplingly significant number of industry players in China are now sanctioned.

Last week, C.C. Wei (魏哲家 Wèi Zhézhā), CEO of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing (TSMC) 台湾积体电路制造 assessed the latest package of U.S. controls starkly: “Geopolitical confrontation has distorted the entire market. Previously, you made a product and could sell it to the whole world. Now, some products are not allowed to be sold, some countries say that you are not allowed to enter, while some say you can only use certain [local] products.”

He told his audience at an event hosted by the Monte Jade Science and Technology Association, a business networking group started by Chinese-Americans in Silicon Valley in 1989: “The situation has destroyed all the productivity and efficiency brought by globalization. Even if saying destroying is too strong, these barriers will seriously affect the benefits of a free economy like in the past. This is really bad.”

Wei said he regretted the decline in trust. ”If you ask the U.S. and China to work together, it isn’t easy. Mutual trust and collaborations were the key for human beings in the past to make advancements, and now this is weakening. It’s not a good sign.”

Chips were a product of globalization and now it’s over

Wei should know: Outside China, his firm was an early victim of the geopolitical confrontation between the U.S. and China, losing 15-20% of its revenue when Chinese telecom giant Huawei 华为 was targeted by new U.S. extraterritorial export controls in 2020. More recently, TSMC has lost customers as the U.S. has expanded its bans on Chinese companies, and TSMC is obligated to comply with those bans.

In addition, TSMC must now try and determine if Chinese semiconductor design firms using its chips have run afoul of performance thresholds for advanced designs — in other words, TSMC must do due diligence on its customers, something no foundry is equipped to do.

One of TSMC’s manufacturing facilities in China in Nanjing was also hit with end use controls rolled out in October, putting future investment in what was once considered a significant asset at risk.

Wei’s concern about the long-term impact of steady and forced severing of multiple complex global supply chain links via government fiat is shared by many in the industry.

Before 2020, the semiconductor industry had been largely driven by market forces, global free flows of capital and personnel, and increasingly efficient supply chains. That era is over, and whatever the U.S. does, Chinese officials are completely rethinking how Chinese companies will be able to develop ”hard” or “core” technologies such as semiconductor design and manufacturing, and where they will get advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment.

Officials in Beijing have been considering options for both challenging U.S. actions multilaterally at organizations like the World Trade Organization (WTO), and punishing specific U.S. companies.

China’s leaders also seek to boost domestic manufacturing through increased investment in research and development, as well as by fast-tracked listings for semiconductor firms on domestic stock exchanges, such as the Science and Technology Innovation Board (STAR market) in Shanghai. Beijing is also considering whether to push back against the U.S. in areas in which China dominates critical supply chains, such as rare earth minerals and components for batteries for electric vehicles.

China at the WTO

Until this month, Beijing had not pursued action within the existing international trade regime. That changed when on December 12, when a request from China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) was circulated among members of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) for dispute consultations with the U.S., challenging export controls “with respect to certain advanced computing semiconductor chips and manufacturing products, supercomputer items, as well as related technologies and services, destined for or otherwise related to China.”

A MOFCOM official from the Department of Treaty and Law explained the decision in fairly strong language, accusing the U.S. of “threatening the stability of the global industrial chain …violating international economic and trade rules… and harming global peace.”

But China’s WTO letter appears to be largely symbolic, as the submission of a complaint is only the first step in the WTO’s lengthy dispute resolution process — the U.S. side now has 60 days to enter into consultations with MOFCOM on the issue. U.S. officials at USTR reacted to the request with a terse statement: saying that the WTO was “not the appropriate forum to discuss issues related to national security.” Assuming the U.S. is unwilling to engage in consultations, Beijing can request the establishment of a WTO panel, but it would be a long slog.

Chinese officials are also almost certainly looking again at the use of legal tools put into place over the past two years that would allow some targeted responses, such as punishing U.S. companies or individuals that comply with American export controls. with sanctions, asset freezes, or visa denials.

China has three new sets of “Blocking Rules,” which provide a broad legal basis for retaliation: the Unreliable Entity List (announced 19, details in 2020), the Anti-Foreign Anti-Sanctions Law (AFSL, 2021), and the Counteracting Unjustified Extra-Territorial Application of Foreign Legislation and Other Measures (Extra-territorial Rules, 2021) establish a comprehensive legal framework that will likely be the basis for some level of response in early 2023.

How the U.S. started hitting Chinese tech firms: Huawei and ZTE in 2016

Since the U.S. imposed export controls on China’s big two networking equipment and telecommunications companies Huawei and ZTE 中兴通讯 from 2016 to 2019, Beijing has been refashioning its industrial policies to become more self-reliant.

This approach has taken many twists and turns to establish lists of “secure and controllable” technology and designate domestic firms as preferred suppliers, fast tracking a domestic science and technology board at the STAR stock market in Shanghai, incentives and new ways to provide capital for the domestic semiconductor industry.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

Corruption at the Big Fund means Beijing needs a new plan

Another serious challenge for China’s tech industry is allegations of widespread corruption. In the summer of 2022, China’s corruption regulator launched a series of investigations into some of the country’s leading figures in the semiconductor industry. Many work directly or indirectly with the state-backed China National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund, also known as the Big Fund.

Established in September 2014, the fund has been instrumental in nurturing China’s homegrown chipmakers, including successful examples like Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp. (SMIC) 中芯国际 and Yangtze Memory Technology Corp. (YMTC) 长江存储科技. Politicians in Beijing are now demanding proof that massive state investment in the Big Fund has in fact brought tangible benefits.

So Beijing needs to retool: In December, reports suggested that the government is preparing a nearly 1 trillion yuan ($150 billion) package of tax and other incentives to help the semiconductor industry. The plan is likely to offer Chinese companies financial assistance if they buy semiconductor equipment manufactured by other Chinese firms. Already, memory leader YMTC has issued tenders for domestic equipment suppliers to compensate for a restriction of trade with the U.S.

But those domestic equipment suppliers themselves have been hit by U.S. controls. Shanghai Microelectronics Equipment (SMEE) 上海微电子装备 was just added to the Entity List in the mid-December Commerce Department release. SMEE is a lithography company: it makes machines which use light to print patterns on silicon wafers an essential part of making chips. (ASML of the Netherlands is the most famous lithography company, and U.S. rules mean it cannot sell its most advanced machines in China.)

This issue is likely to be considered ahead of the 13th National People’s Congress that is due to start in Beijing on March 5 2023, but it isn’t only the Chinese government that wants a domestic chip industry: Huawei has also invested heavily in building a vertical semiconductor manufacturing supply chain. Huawei appears to be attempting to follow a model more like South Korean giant Samsung, and develop its own capabilities, and is making targeted investments to create a complete local semiconductor supply chain.

Coupled with government backing, some industry observers hold that the combination of Huawei’s business acumen and strong corporate culture, this type of semiconductor supply chain investment strategy could prove more effective than a pure government top down effort. Like Samsung, Huawei itself would be a huge consumer of the semiconductors produced via the ecosystem it is investing in.

Here though, U.S. export control officials appear to have anticipated elements of Huawei’s strategy, and the US is targeting key parts of the firm’s budding semiconductor ecosystem, including a Huawei-backed chip maker PXW Semiconductors 鹏芯微集成电路, and Shanghai Integrated Circuit Research and Development Center 上海集成电路研发中心. Huawei has recently filed patents for some technologies key to advanced manufacturing, such as cutting edge lithography, but will face major technology development and systems integration challenges, along with U.S. efforts to thwart China’s tool makers from moving up the technology ladder by denying key U.S. inputs.

Cutting off the electric car battery supplies?

Finally, Beijing is almost certainly considering other long-term responses.

Beijing has a potentially strong asymmetric tool in the dominance of Chinese firms in critical mineral supply chains that are key to electric cars and other green technology. China could choose to weaponize the supply chains of rare earths, magnets, and graphite, cobalt, nickel, and lithium. But this would come with major downsides for Chinese firms, and result in further acceleration of U.S. and allied country efforts to reduce dependence on China.

Climate change has been touted as a transnational existential issue ripe for U.S.-China collaboration coming out of the November Biden-Xi summit in Bali, and this could mean Beijing would be reluctant to take measures that would drag green tech supply chains further into the realm of bilateral tensions.

The immediate fallout

The domestic semiconductor industry is going to feel the last few months of U.S. activity very soon. Firms will slow down and have to lay off staff. Some will be irreparably damaged

There will be more workarounds in some areas, depending on the technology and the state of domestic research and development, and less in other areas.

Beijing’s preferred short-term response will be to continue pushing self reliance. while carefully considering a set of punitive measures designed to minimize domestic fallout. No doubt there will be actions at multilateral institutions approaches that will primarily be symbolic but play to China’s allies, all amid further bifurcation of the technology landscape.