Two billion eyes and a billion wallets: Short video ecommerce is thriving in China

TikTok’s potential death throes in DC were live streamed across the world last week, but China’s domestic short video platform ecosystem is in rude health, buffed up by live streaming ecommerce.

In December 2022, the number of people in China watching short-form videos surpassed 1 billion, an increase of nearly 400 million in the last five years alone. The short video industry as a whole is projected to be worth nearly $180 billion by 2026, with an estimated annual growth rate of over 30%.

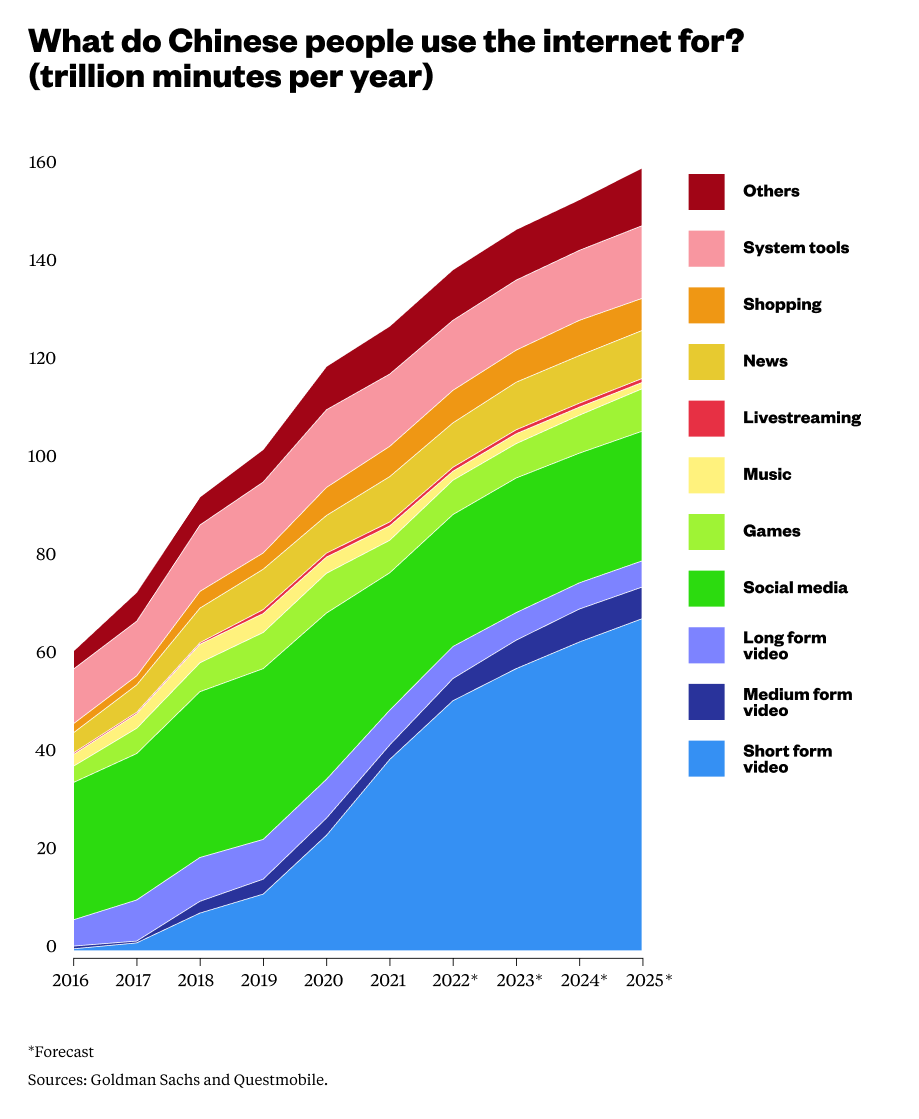

There are more than a billion mobile users on Douyin, Kuaishou, and Tencent Video within WeChat. According to investment bank Goldman Sachs, 60% of these are active on a daily basis, spending on average 120 minutes a day watching short videos. Short videos (which last 30 seconds on average), accounted for 31% of Chinese people’s online time — more than any other type of entertainment consumed.

This trend is set to increase further over the next few years, with people spending more time watching short videos than on traditional social media, listening to music, consuming news, gaming, or any other online activity.

In December 2022, Research and Markets projected an upsurge in demand for video content in China, with the key drivers being accelerating penetration of 4G and 5G networks, and rising preference for live streaming over social posts.

A report from the China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC) released in early March 2023 highlighted the combination of content and ecommerce (内容+电商) as a key factor, and interestingly singled out county-level opera troupes as an example of organizations that rely on ByteDance’s platform Douyin as an important revenue source.

This subtly speaks to the government’s preferred focus for the platform economy: It is wary of digital distractions from the “real” economy and the erosion of traditional cultural norms that social media can lead to. As such, the government’s preferences are arguably the biggest risk factor to the growth of the sector in the years to come. For example, Douyin already heavily restricts usage by minors on its platform, and the regulatory decimation of the online tutoring industry is still an uncomfortably recent precedent.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

The main players

Among the three industry leaders, Douyin — TikTok’s sister app for users in the P.R.C. — currently dominates the market, and is projected to account for 50% of time spent online by users in China by the end of 2025. Kuaishou follows with 30%, and Tencent’s WeChat Channels make up the remainder.

These three apps provide similar kinds of content, and are converging in interesting ways with regards to ecommerce and monetization strategies. However, there are important differences between them in terms of their origins and product offering.

Douyin has grown rapidly in the years since its launch in 2016 to become China’s largest online advertising platform in terms of revenue, surpassing Alibaba in 2021, in part because it has attracted so many monthly active users (MAUs) — 730 million in November 2022.

Douyin began as an entertainment app, and it has had to balance monetization with user experience: too much advertising could turn viewers away. It recently restricted traffic for ecommerce content (live streaming and short videos) to less than 10% of what users are exposed to, according to Tech Buzz China.

Kuaishou began as a tool for creating animated GIFs in 2011, but soon transformed into a video app that became popular among rural residents — China’s first generation of farmer-creators.

Unusually for such platforms, Kuaishou maximizes the number of different creators that users are exposed to, rather than focusing on promoting the most popular influencers — known as Key Opinion Leaders or KOLs. Kuaishou is particularly good at building loyal communities of users and merchants where people feel comfortable buying from streamers whom they feel that they can trust.

Tencent has come much later to the short video game, but it has a superpower: the ubiquitous WeChat, which began life as a messaging service but now offers almost every digital service you can think of and has over 1.3 billion users. Ecommerce offerings on the WeChat Channels video platform increased by more than 800% year-on-year in 2022, with the average transaction value now exceeding 200 yuan ($29).

Tech company veteran and investor Eugene Wei says Tencent is “desperate to cool off ByteDance’s momentum in the short video space.” Indeed, it recently engaged celebrities such as Taiwanese pop icon Jay Chou (周杰伦 Zhōu Jiélún) and the Irish band Westlife in pursuit of these goals.

But Channels seems unlikely to catch up with the two incumbents, with their enormous user numbers and rapidly diversifying offerings. For instance, both have partnered with food delivery companies: Douyin with food delivery and ecommerce platforms Ele.me and Kuaishou with Meituan. It would be foolish, however, to write Channels off. Tencent has been playing to win since it was founded in Shenzhen in 1998 with the QQ desktop messenger as its main product, and its founding CEO Pony Ma (马化腾 Mǎ Huàténg) has reportedly called Channels “the hope of the whole company.”

Ecommerce, not advertising, is the key to short video success

Barring regulatory brakes on growth, there is every reason to believe that the leading firms in the sector will continue to go from strength to strength. These companies have traditionally monetized through advertising. Increasingly however, given the user fatigue that comes with standard advertising content, they are now focusing heavily on short video ecommerce as a revenue source.

As the CNNIC report makes clear, part of the success of these platforms is via what they call “seeding grass” (种草 zhǒngcǎo), referring to a process of carefully encouraging users to buy their products by feeding them content that shows other users or KOLs wearing or displaying them. It’s something like product placement in movies, but adapted for the mobile phone video age.

The entry point for ecommerce for these firms has been live streaming, but recently the main players have also branched out into shelf-based shopping (in which online services enable offline purchases at local brick-and-mortar stores), and into fields as diverse as recruitment, food delivery, and even real estate.

The strategy is working. While Alibaba’s Taobao and JD are still the go-to places for China’s online shoppers, the short video platforms are steadily eroding their market share. Goldman Sachs predicts that the video platforms’ Gross Merchandising Volume (GMV) — the key metric to quantify ecommerce sales — will grow from 3% of total online retail in 2019 to a projected 25% in 2025. This would be at the expense of the traditional ecommerce retailers, especially since short video app users spend about six times as long on those platforms as on Taobao and other ecommerce platforms. Douyin will reap the bulk of the rewards, with Alibaba losing a significant chunk of its majority share.

The takeaway

Short videos are here to stay. Despite the Party-state’s concerns about the negative effects of these platforms, they represent a key tool to boost household consumption this year — one of the government’s stated economic goals.

Companies:

- ByteDance

- Tencent

- Xingin Information Technology (Xiaohongshu)

- Beijing Yixiao Technology (Kuaishou)

- Zhejiang Taobao Network (Taobao)

- Alibaba Group

Sources and additional data:

- Short-form video-rization: Assessing the potential ceiling and lessons from China / Goldman Sachs

- The rebirth of Xiaohongshu / Tech Buzz China Insider

- Food Fight! Douyin’s local services / Tech Buzz China Insider

- WeChat Channels – The Hope of Tencent / Tech Buzz China Insider

- A billion short video users, Bilibili annual revenue up by 13% and Luckin Coffee’s up by 66.9% / The China Project

- Temu vs Shein: Which platform will rule the ecommerce world? / The China ProjectMore Than Just TikTok, What you Should Know about Chinese Short Video Apps / China Project

- Owning the funnel / Lillian Li at Chinese Characteristics

- Livestreaming monetisation models / Lillian Li at Chinese Characteristics

- Internet and the murmurs of post-modernity in China / Lillian Li at Chinese Characteristics

- The Gamification of the Chinese Consumer / Lillian Li at Chinese Characteristics

- Battle Royale, Time Machine Management and Why We Should Copy More / Lillian Li at Chinese Characteristics

- What I talk about when I talk about Chinese tech / Lillian Li at Chinese Characteristics

- Premium: Your superapp needs a content strategy / Lillian Li at Chinese Characteristics

- The product philosophy of Kuaishou / Lillian Li at Chinese Characteristics

- Xiaohongshu deep-dive / Lillian Li at Chinese Characteristics

- An introduction to Bilibili / Lillian Li at Chinese Characteristics

- The mental models of Chinese tech / Lillian Li at Chinese Characteristics

- Seeing Like an Algorithm / Eugene Wei at Remains of the Day

- Status as a Service (StaaS) / Eugene Wei at Remains of the Day

- American Idle / Eugene Wei at Remains of the Day

- 长草族:是什么让我们长草 / China News Service

- “Planting Grass” and RED: How E-commerce in China is Interweaved with Social Media / MIT Global Media blog

- Are Americans Worried About Chinese Apps? / Kevin Xu at Interconnected

- China: short video market size 2023 / Statista

- Number of monthly active short video users in China 2018-2022 / Statista

- China Short Video & Live Streaming Market to Reach $179.24 Billion by 2026 at a CAGR of 33.46% PR Newswire

- 小红书调整组织架构,押注直播电商,结束社区和商业化之争 / LatePost

- 王兴的「外卖」,张一鸣抢得走吗? / 36Kr

- Tencent ramps up bet on short video platform in ByteDance challenge / Nikkei Asia

- William Davies · The Reaction Economy / London Review of Books