Why Chinese people don’t hate their government

It may seem counterintuitive to many Westerners, but many Chinese people, including — and perhaps especially — younger people, seem to be very happy with the performance of their government. Economics, history, culture, and, yes, propaganda all play a role in shaping attitudes.

To many Westerners, especially Americans, the idea that Chinese people don’t hate their government seems counterintuitive. What about the Cultural Revolution and the famines and social disruptions caused by terrible policies and ideological campaigns in that era and earlier? What about the more than a million Uyghurs interned in camps today, and the rights lawyers and activists behind bars on trumped-up charges? What about the strict censorship of the internet, books, movies, and even speech at universities? Who could possibly like a government responsible for all these horrible things?

However, many Chinese people, including — and perhaps especially — younger people, seem to be very happy with the performance of their government. There is no political polling in China, so there is no way of knowing how common such attitudes are. But anyone who spends time talking to Chinese people at home and abroad, or absorbing Chinese social media, will quickly notice openly expressed patriotism that is not being coerced.

So why do so many Chinese people like their government? There are a number of reasons, which we summarize below. It’s important to note two things:

- This is not a defense of the Chinese government, but an analysis of why the Party-state continues to enjoy an obvious level of support amongst a significant portion of the population.

- As long as unhindered surveying of political opinions remains illegal, and while the government continues to penalize Chinese citizens for critical speech, we will never really know what the majority of Chinese people think about their government. But the reasons outlined below are frequently heard and cited for the Party’s ongoing success at pleasing at least some of the people, most of the time.

It’s the economy, stupid!

In 1978, China began to open up to foreign trade and investment, and allowed individuals and private companies to do business. In the 40 years since then, China’s economy has grown at an astounding pace, with real annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth averaging nearly 10 percent through 2018, which the World Bank calls “the fastest sustained expansion by a major economy in history.” As a result, says the World Bank, “more than 850 million people have lifted themselves out of poverty.”

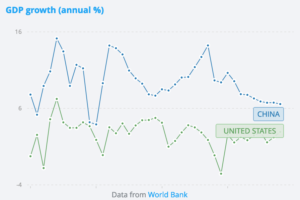

By comparison, annual GDP growth in the United States during the same period was rarely higher than 4 percent, and the average annual growth is around zero because of negative growth years.

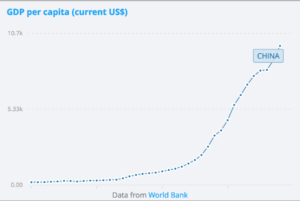

Here, we have linked to World Bank data on China’s per capita GDP growth since 1980, and here we have linked to the annual growth rate of the U.S. vs. China. (You can view snapshots of these charts below, however, the World Bank links will grant you access to interactive versions of the charts.) Note that China’s per capita GDP has more than doubled since 2010 alone, and the different impacts of the 2009 Global Financial Crisis on the two countries growth rates.

The median age of the American population is 37. This means that half of the population is under that age. These young Americans have grown up with endless foreign wars and witnessed one major recession. The median age of China’s population is also 37, but these young Chinese have never seen anything but a booming economy and good times. This half of China’s population was entirely born after 1980, during the period of sustained growth you see in the charts above.

Thanks to government stimulus and the momentum of the previous 30 years of growth, the average Chinese person barely felt the 2009 Global Financial Crisis. In fact, that was the year when Chinese government officials and academics began publicly expressing doubts about the American and Western economic and political systems. As one economist put it:

China’s ability to bounce back quickly from the impact of the crisis has cemented China as a leading actor in attempts to reform global economic governance, and has led many to rethink the efficacy of strong state-led developmental strategies vis-à-vis (neo)liberal alternatives.

In other words, many people saw 2009 as proof that the Party is doing an excellent job with the economy. Despite rampant inequality, survey after survey shows that Chinese people are on the whole optimistic about the future, and feel that their standard of living is improving. Two recent examples:

- Nearly 9 in 10 Chinese people believe their country is “on the right track,” making China the most optimistic country in the world, according to a 2017 Ipsos survey. In comparison, only 43 percent of Americans had a positive view of their country’s direction.

- Chinese teenagers are particularly optimistic, according to another Ipsos survey in 2018, with 94 percent of Chinese aged 12–15 saying they were optimistic about their country’s future, compared with 64 percent of their American peers.

One important source of all these happy feelings is that the Chinese government engineered an urban middle class whose prosperity is connected to political stability. The economist Andrew Batson calls it “one of the most important and least understood events in its modern economic history.” This is what happened:

In the 1990s, as economic reforms were really taking hold, the government allowed some state-owned firms to go out of business or to lay off large numbers of workers. These were people who thought they had a job for life that included housing and healthcare. So state-owned firms — even the ones that were not going out of business or sacking large numbers of staff — gave their employees apartments either for free or at very low prices. Batson, the economist, says the resulting “launch of a private housing market…created the major source of private household wealth” in China.

What will happen if there is a major recession? Who knows. Whereas many Chinese people older than 50 have memories of being hungry as children, anyone younger than that has only known a booming economy.

The government is competent

Sure, the Communist Party has made many mistakes in the 70 years it has ruled China. But in the last four decades, it has had more successes than failures. Basic social services have continuously improved — for most people — since the 1980s. China’s roads, trains, and planes were once dirty, slow, and unreliable; now they are amongst the world’s best. In the 1990s, the word for tourism (旅游 lǚyóu) was novel for most of China’s population; today, there’s not a single country in the world that Chinese tourists do not visit. These are just a few examples of the ways that the Party has proved its competence to many of the people it rules.

Fear of foreign domination and chaos

Conflict with foreign powers in the 1800s, most notably the Opium Wars, brought the Qing Dynasty that was governing China to its knees. China was forced to sign a series of treaties with Britain, France, Japan, Germany, and Russia that conceded ports and vast swathes of land, and gave foreign powers extraterritorial rights.

This is what the Chinese call the century of humiliation (百年国耻 bǎinián guóchǐ), and every child learns about it at school. The Qing dynasty began in 1644. At the height of its powers, it expanded China’s territory to include Taiwan, Tibet, and what is now called Xinjiang.

But by 1911, when the dynasty fell, it was weak and not even able to control events in the capital, Beijing. Then followed nearly four decades of civil war, and rule by vicious warlords.

When the Chinese Communist Party took control of Beijing in 1949, the fighting stopped. But other kinds of chaos came soon: famines caused by bad policies and perhaps worst of all, the Cultural Revolution (1966–76), during which young Red Guards ran amok terrorizing teachers, Party leaders, and any figure of authority who was unlucky enough to come under scrutiny.

Given this history, it is understandable that the average Chinese person might prefer a strong — even authoritarian — central government above the frightening possibilities of disorder.

The education system, media, and propaganda

As mentioned above, all Chinese schoolchildren learn about the “century of humiliation,” and they are taught a version of history of the last century that highlights all the positive things the Communist Party has done while omitting any study of the Cultural Revolution and other Party-produced disasters.

The same messaging and way of seeing history is taught throughout the educational system, and it is imposed on media reports, films, plays, video games, and even WeChat messages. Alternative versions of history and open questioning of the Party are ruthlessly censored.

What is not taught in the Chinese education system: liberal ideas of critical thinking or the idea of individual rights. So while it is not impossible to find uncensored news and history in China, it is so inconvenient that most people do not even bother to try.

Cultural factors

Although Taiwan proves that a culturally Chinese polity can form a perfectly respectable democracy, it is true that for most of China’s history, it has been run by strong central governments with one man in charge whose word is law. Confucian thought is of course an important part of China’s cultural fabric, and if there’s one thing that Confucius was very clear about, it was the need to respect authority.

Many Chinese people argue that theirs is a more collectivist society, which means that they’re willing to give up some individual rights in exchange for prosperity and the greater good. This argument suits the Chinese government just fine.

What could go wrong?

“Authoritarian regimes are stable, until they suddenly aren’t” goes the old saying. Part of the problem with judging the stability of the Chinese government is that there is no independent source of data about citizen satisfaction. But you can find plenty of evidence of dissatisfaction with society in China, even if it is not directed at the central government. For example, income inequality is an enormous problem, and has reached levels close to in the U.S.: There are still rural residents without access to running water while the urban rich — who are often connected to the political elite — crash Lamborghinis for fun. Sound like the French Revolution much?

So if some catastrophic event — perhaps a massive food safety failure, an infrastructure disaster, or a significant market crash — were to set off a chain of events leading to a revolution, it would be easy to say, “Ah, the signs were there all along!” But right now, most of the signs we see point to the Chinese people becoming more — not less — supportive of their government. As Beijing faces attacks from the United States on multiple fronts, and growing criticism from the international community, this trend is likely to continue.