This article was originally published on Neocha and is republished with permission.

After the Cultural Revolution, China opened itself up to the world. As Western culture entered the country, so did its art, and the Chinese people embraced these foreign aesthetics. In 1985, American artist Robert Rauschenberg held ROCI China at the National Museum of Art in Beijing, which, for many, was their first encounter with pop art in the country. Pop art—which originated in the West from a desire to subvert fine-art traditions—became a eureka moment for many Chinese artists, inspiring them and paving the way for a new wave of Chinese art. The artists of this period, ever so eager to break the mold and work outside the bounds of tradition, laid the bedrock of Chinese modern art.

Shandong-born artist Xu Deqi was introduced to pop art in 1998, which he believes wouldn’t have been possible without the foundation set by the early pioneers. Artists directly influenced by Rauschenberg went on to light Xu’s creative wick. At the time, he was studying contemporary art at Beijing’s Academy of Fine Art, having already completed a bachelor’s in oil painting at Shandong Normal University. “My professor was Yi Jinan, who’s now an acclaimed art critic,” he recalls. “He had a profound influence on me. He invited twelve avant-garde artists to speak to the class, and that’s how I was turned onto contemporary art.”

A departure from his background in traditional oil painting, pop art gave him a renewed perspective on art, on how he can express his creativity in bolder strokes. “Contemporary artists in the West are often vehemently against traditional methods,” he says. “But Chinese artists embrace the ways of the old and believe in building atop the roots. This outlook is what makes Chinese art so different.”

Xu’s works reward the studious eye. His canvases are visually dense, populated with familiar motifs culled from real life. The exacting line work and striking colors he employs allow him to blend the surreal with the realistic, and certain paintings draw clear reference to the poster style of the ’70s and ’80s.

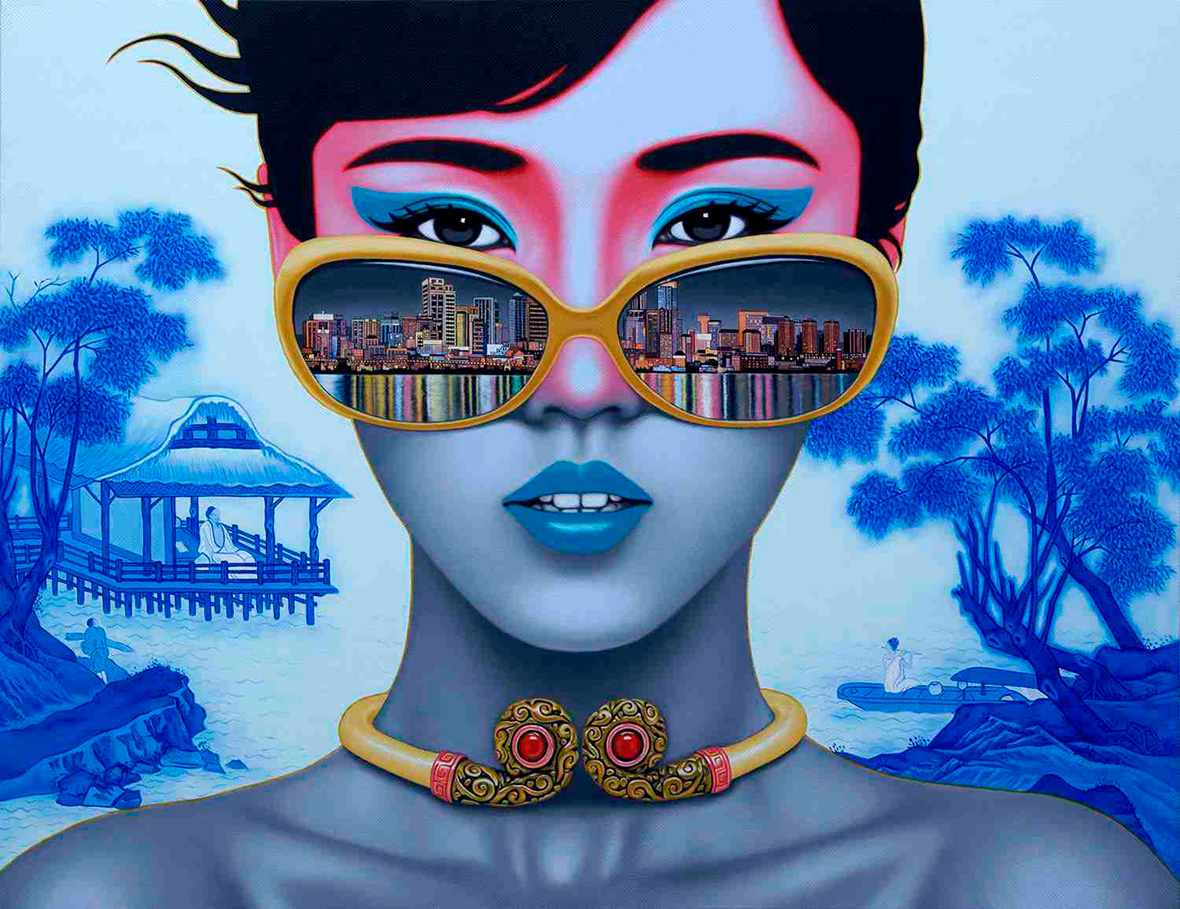

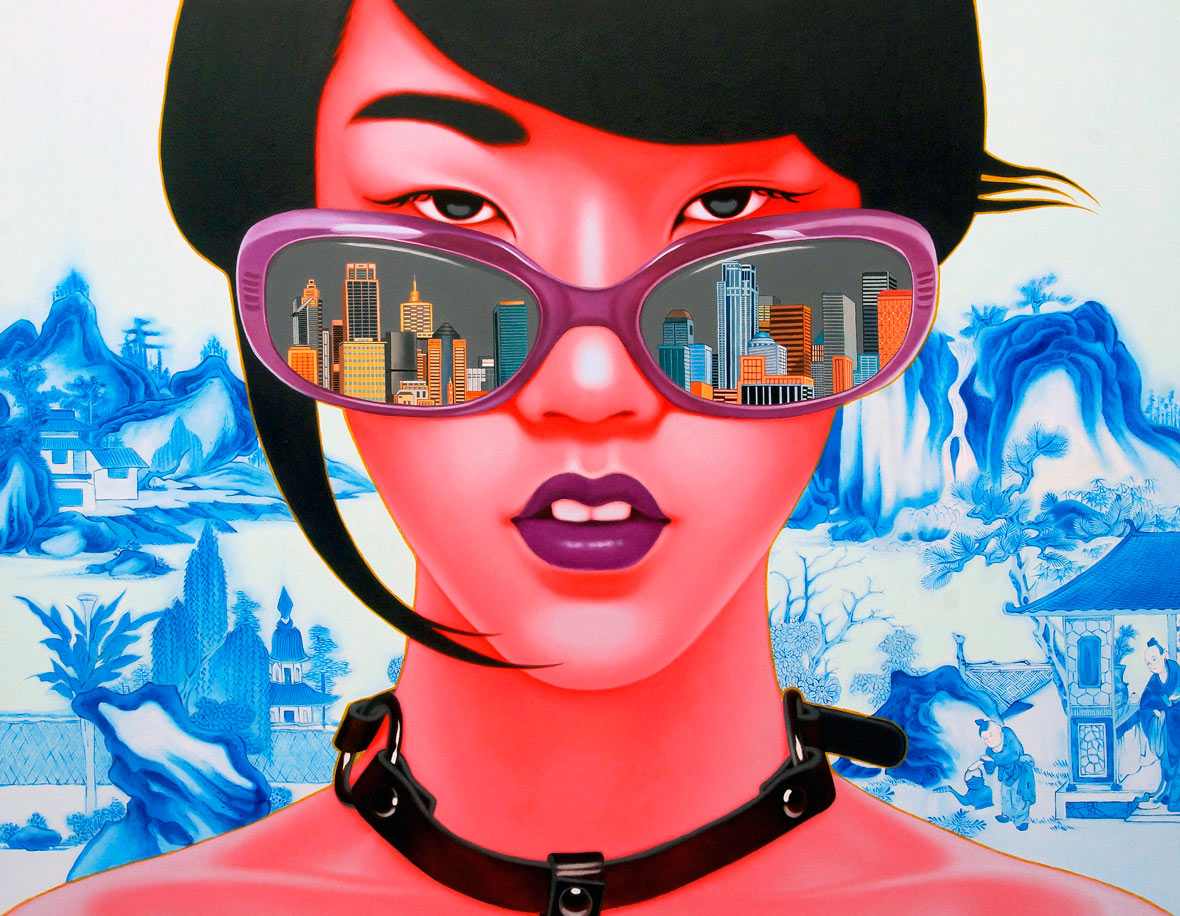

Some of the female protagonists who appear in the Underglaze Blue Girl and China Girl series are based on public figures while others are entirely imaginary. They have one thing in common though. On Xu’s canvases, they’re all fashionistas, and his depiction of their stylish tastes is a meditation on the changing times. The juxtaposition between their vogue poses and the traditional Chinese designs that dot the background is the artist’s commentary on how Chinese society has become more progressive over the past decades. The reflection on their chic sunglasses often represents the growing influence of Western thought, shown in a variety of ways—the London bridge under a clear blue sky, an idyllic picnic with wine and cheese, or skylines of American cities. Amidst this mosaic, a question seems to stand at the forefront: in this age of globalization, will traditions be abandoned or kept alive?

Xu’s art offers a clear-cut answer. With the inclusion of traditional porcelain designs and motifs such as koi fishes, peonies, and qipaos, his contemporary works seem keen on carrying Chinese traditions to the modern age. “In traditional Chinese culture, fishes represent wealth and desire,” he says. “I also see kindness in humans, and there’s beauty in that, especially in how this kindness is unwavering in the face of greed and temptation that pervade today’s society. I try to capture this splendor in my art. On the other hand, the blue-and-white porcelain design that captures the idle life of ancient Chinese is a reminder for city dwellers on the importance in maintaining harmony between nature and man.”

In more recent works, he makes nods to other techniques of traditional Chinese art, with clear nods to the six principles of Chinese painting and the use of negative space. Under his brush, Chinese art history is seamlessly nestled alongside contemporary aesthetics.

Xu has been developing the Underglaze Blue Girl series since 2009, and in his subsequent project, Beauty and the Beast, themes of human nature remain prevalent. The women in the follow-up series are shown walking alongside wild beasts. By painting these human and animal duos with contrasting colors and placing them in uncluttered settings, the characters seem to pop from the frame. But there’s an air of melancholy that hangs over these women, almost as if they’re troubled by unspoken thoughts. “The lions, tigers, and jaguars of the series are symbolic,” Xu explains. “They represent the ailments of modern society. The power imbalances, wage disparity, and disrupted order that test our capacity to be good people.”

Xu was only a child during the Cultural Revolution, but that period of strife left a deep impression on him. The political turmoil of Mao Zedong’s reign is hard to forget, and through his art, he hopes people can reflect on the hard-learned lessons of that time.

Xu refuses to characterize his work as pop art though. With a laugh, he says they’re just “fashion sketches” at best. Admittedly though, pop art has had a tremendous influence on him. But aside from pop art, the surrealism of Salvador Dali and René Magritte has also inspired mischievous parodies. His 2014 series Mao Dali is a clear homage to Dali’s Persistence of Memory, and the 2016 series Maogritte riffs on several of Magritte’s iconic works.

Whether it be through his use of color or the subject matters he paints, a sense of joy and hope radiates from Xu’s canvases. His blending of past and present is excites the imagination, and it’s something he’s keen on continuing. “I don’t know where my art will take me, but I’m sure my curiosity will guide me to exotic places,” he says. “I’ll keep working within the intersection of Eastern and Western culture, and in doing so, push the limits of paintings.”