Queer cinema in Hong Kong, before and after 1997: Q&A with Helen Hok-Sze Leung

The Hong Kong Lesbian and Gay Film Festival has returned after three years of pandemic-enforced restrictions and virtual programs. On this occasion, we recently spoke to Helen Hok-Sze Leung, an expert on queer cinema and Hong Kong culture.

The Hong Kong Lesbian and Gay Film Festival (HKLGFF), one of the longest-running LGBTQ film festivals in Asia, has returned for its 34th annual celebration of queer cinema. This year’s event, which runs from September 8 to 23, features a diverse selection of in-person screenings and panel discussions.

As a vital platform for LGBTQ visibility, communication, and acceptance, the latest edition of HKLGFF marks a triumphant return for the festival after three years of pandemic-enforced restrictions and virtual programs.

“It’s been a challenging three years for everyone due to COVID, but sometimes challenges can bring unexpected positive outcomes. We have all learned how to navigate uncertainty,” wrote Joe Lam, the festival’s director, on its official website. “Since we are fully open, we can now fly in overseas directors and crews to attend the festival.”

In light of the return of HKLGFF in its full glory, I recently spoke to Dr. Helen Hok-Sze Leung, a professor at the Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies at Simon Fraser University in Canada, who has extensively researched queer cinema and Hong Kong culture. We talked about the history of queer cinema in Hong Kong before and after the 1997 handover, the close entanglement between queer expressions and popular culture, the impact of the National Security Law on the local film industry, and what it means to be “queer” during a time of uncertainty.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Nathan Wei: Your first book, Undercurrents: Queer Culture and Postcolonial Hong Kong (2008), studies Hong Kong’s queer culture in the 1990s, primarily via the lens of cinema.

However, different from our common understanding of the category of “LGBTQ movies,” most of the films you analyze do not feature self-identified LGBTQ people or stories. Rather, they showcase more of what you describe as “queer undercurrents.”

For instance, in an analysis of Sister Thurston, the leader of a triad society branch in Portland Street Blue (古惑仔情義篇之洪興十三妹 gǔ huò zǐ qíngyì piān zhī hóng xìng shísān mèi) (1998), an installment in the Young and Dangerous movie series, you put forth the possibility of reading this butch “woman” as a transgender masculine person who formed homoerotic ties with her triad “brothers,” despite her gender or sexual identity never being made clear in the movie.

Another thing that I find fascinating is that most of the movies are commercial ones produced by big studios. Can you talk a bit about the historical background of these queer undercurrents within mainstream popular culture, and how has it changed since then?

Leung: My book is essentially dealing with the period of Hong Kong prior to its sovereignty transfer to China in 1997, when the local film industry was very productive and Hong Kong popular culture was still at its zenith. What I find are these undercurrents of queer expression, eroticism, and genders in commercial films that mass audiences saw and loved. This existed in contrast to the very little progress made on LGBTQ legal rights — homosexuality was only decriminalized in 1991 and popular support was still quite low.

Similar to colleagues who study other Asian societies, I was trying to point out that queer culture is not necessarily the same as having queer rights. This is not to say one way is better than the other, but to show things are more complicated.

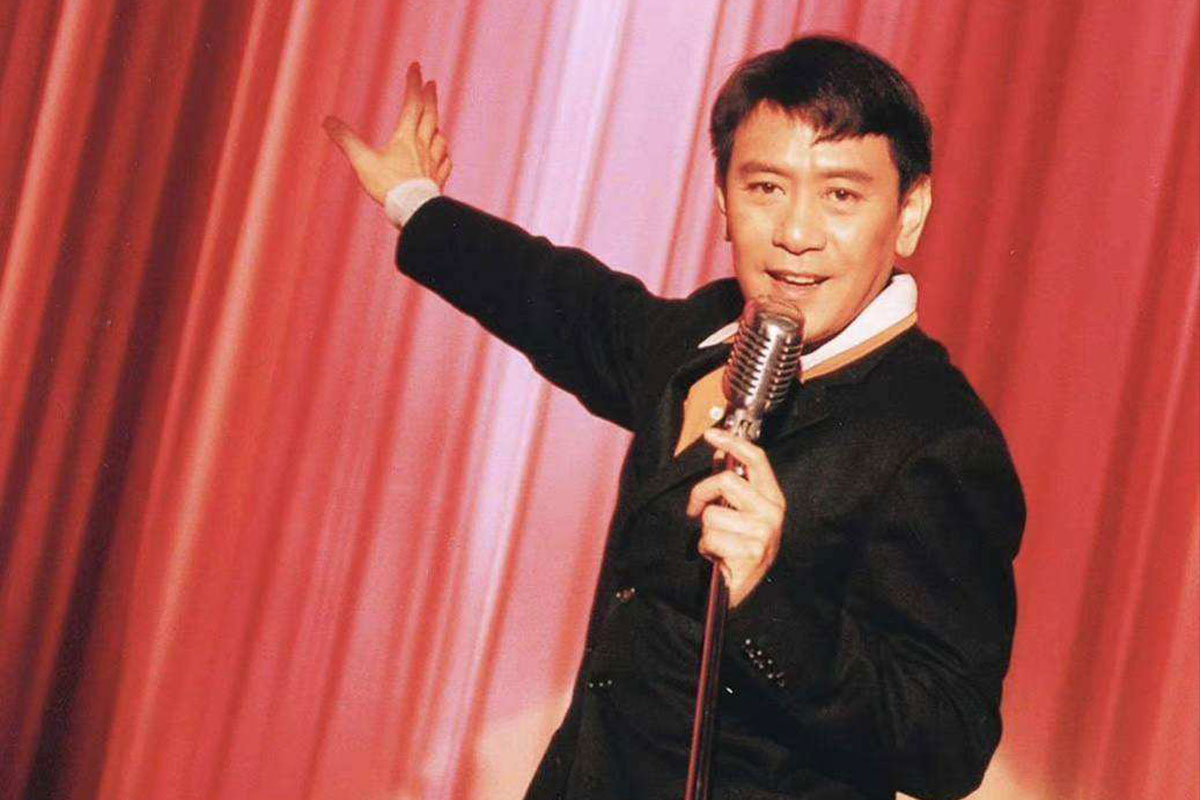

What has changed? Interestingly, there has been much clearer identity-based LGBTQ politics since then, with more overt LGBTQ activism and queer celebrities coming out in the mainstream culture, such as Anthony Wong Yiu-ming (黄耀明 Huáng Yàomíng) and Denise Ho (何韵诗 Hé Yùnshī).

Post-’97 has witnessed rapid politicization and rise of social movements, especially among young people. This was very different from the 1970s and 1980s, when I was growing up in Hong Kong. Back then, young people were indifferent to political matters under British colonial rule.

But after the sovereignty transfer, there was a real awakening of political consciousness and political identity, including LGBTQ identity. But while that’s happening, we have seen much less queer expression in mainstream commercial films since the late 1990s, and LGBTQ figures and stories mostly can only be found in independent films, forming a demarcation between commercial and independent cinema.

Can you give us some examples of this change?

Leung: For me, the representative figures would be two Canton-pop stars, Leslie Cheung (张国荣 Zhāng Guóróng) and Anthony Wong.

Leslie Cheung showcased a very ambiguous queer identity, what can be called a “glass closet” — everybody knows, but he would never really say it. If you look closely at what is often seen as his “coming out” moment, it was during a 1997 concert tour called “Red” where he dedicated a song to his same-sex partner, Mr. Tong, who he addressed as his “mother’s godson.” He didn’t actually come out as gay.

In contrast, Anthony Wong explicitly said that “I am gay,” in a concert in 2012. And perhaps to avoid any misunderstanding that might be caused by the pre-existing undercurrents, he reiterated that “I am a homosexual. I am a gay, G-A-Y, gei-lou (Cantonese slang for gay man). I am attracted to men.”

These two coming out moments sums up the generational difference.

This is a very interesting contrast. Before delving into the post-’97 situation, can you explain a bit more about why pre-’97 mainstream filmmakers liked including queer-like characters or stories in their films, and furthermore, why did the audience enjoy watching this content?

Leung: My own argument is that this is already in the culture itself. One source of inspiration for filmmaking was Cantonese opera, which itself has a long tradition of cross-dressing. My grandmother loved it, especially this diva Yam Kim-fai (任剑辉 Rèn Jiànhuī), a woman actor who played multiple male roles on stage. Similar to Leslie Cheung, Yam was also in a glass closet. People knew she lived with her female acting partner for her whole life and would just assume they are a couple, but they would never call them lesbian.

The other type of genre that I wrote about is the girls’ school stories. There are many elite girls’ schools in Hong Kong, and I also went to one. Many of them were Christian schools, but based on my own experience and conversations with other people, a lot of homoeroticism happened in those schools. It’s almost the opposite of bullying: the athlete students in high schools with short hair were especially popular among other girls, who would worship and have a crush on them. Ninety percent of the time these girls went on living a heteronormative life after graduation, but in school, nobody questioned this queer eroticism. When seeing films that draw on these stories, the average audience would find a sense of familiarity: “This is something I know of. It’s in my culture, and it’s interesting.” I actually believe queerness is always in the culture, and people have a bigger capacity for accepting them.

This sounds very different from the stereotypical narrative that depicts Chinese culture as family-centric and thus conservative and homo/transphobic.

Leung: It is homo/transphobic, but expressed in a different way. Being queer or trans is considered not so much as a sin against God, but more as something “improper” or threatening to Confucian family values. Parental acceptance is possible as long as you don’t name it. Leslie Cheung’s address of his lover as his mother’s godson is an illustrative example, a gesture to find him a place in the family. I also know other cases where one is included in their same-sex partner’s family as an “adopted child” by the parents.

I also want to add that there are a handful of social issue films in the 1990s that do have explicit gay characters and talk about homophobia. One example is A Queer Story (基佬40 jī lǎo), a 1997 film made by Shu Kei (舒琪 Shū Qí). That period was not all about the undercurrents that I describe.

I want to turn to the post-’97 situation. Can you talk a bit more about what has happened to Hong Kong films since the late 1990s? Why did queer expressions gradually disappear from mainstream commercial films?

Leung: It is related to the decline of the local film industry since the late 1990s and the early 2000s. With the film market in China being opened up, many Hong Kong filmmakers went up north. Instead of making films for local audiences, they turned to either co-produced films or Chinese films, to meet the larger demand of that vast market. While gaining more economic profit, however, they also run into Chinese censorship, which does not allow queer content on the silver screen, therefore leaving little space for queer undercurrents.

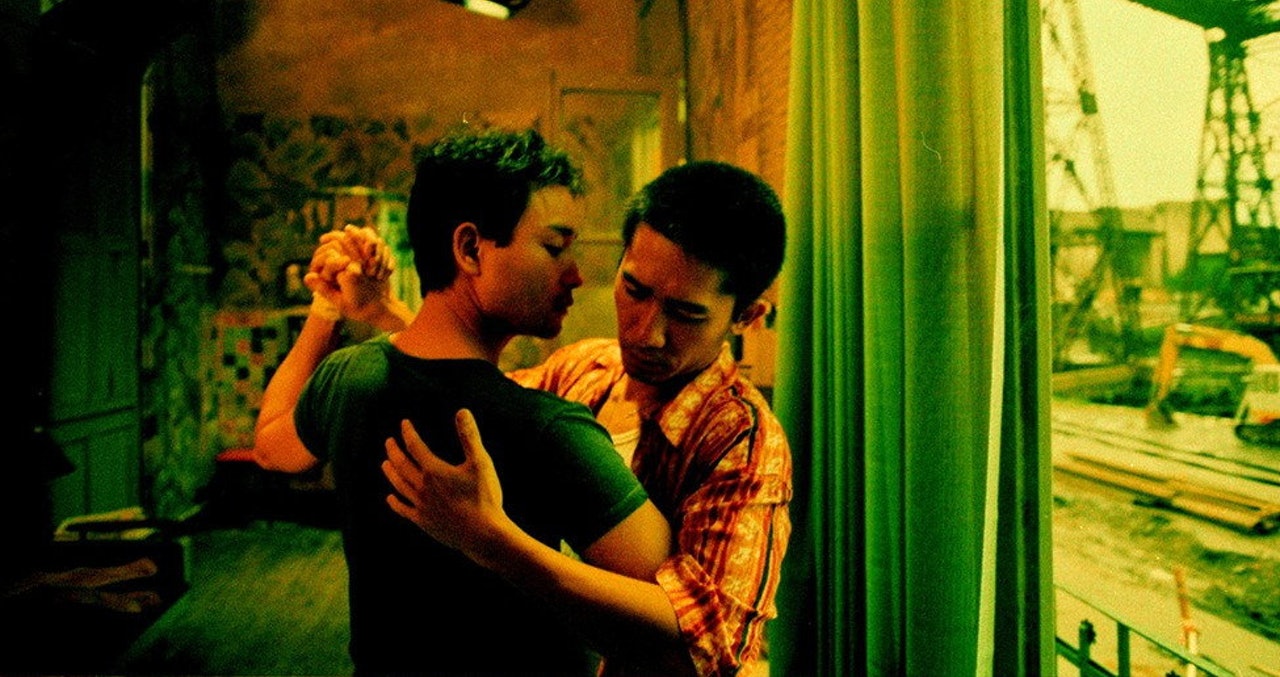

I remember when director Stanley Kwan (关锦鹏 Guān Jǐnpéng) was making Lan Yu (蓝宇 lán yǔ), he had to shoot the film illegally as he did not have a permit from the Chinese administrators. With the disappearance of queer undercurrents from mainstream films, LGBTQ expressions can only be found in the local independent films, as producers in that field don’t care much about the market, thus also less affected by censorship.

Can you briefly introduce some of the representative independent queer films in this period?

Leung: Some of the names I can think of include Danny Cheng Wan-Cheung (云翔 Yún Xiáng), also known by his professional name Scud, a productive director whose movies showcase more the “decadent” gay life, like drug use and queer people experimenting with polyamorous relationship, including City Without Baseball (无野之城 wú yě zhī chéng) (2008), Amphetamine (安非他命 ān fēi tā mìng) (2010), Utopian (同流合污 tóng liú hé wū) (2016), etc.

And Simon Chung (钱德胜 Qián Déshèng), whose I Miss You When I See You (看见你便想念你 kànjiàn nǐ biàn xiǎngniàn nǐ) (2018) tells a story about high school homoeroticism, similar to the girls school films I mentioned, but amongst boys.

A more recent one is Twilight’s Kiss (叔·叔 shū·shū) (2019) by Ray Yeung (杨曜恺 Yáng Yàokǎi), a film based on sociologist Travis Kong’s oral history research on elder gay men. It was the first time I saw a clear linking up between queer cinema and academia.

One noticeable phenomenon is that most of these independent films were made by out gay — mostly men — filmmakers, whereas for directors of queer movies from the previous period, only Stanley Kwan is openly gay. Others such as Ann Hui (许鞍华 Xǔ Ānhuá), who directed All About Love (得閒炒飯 déxián chǎofàn), and Wong Kar-wai (王家卫 Wáng Jiāwèi), who made Happy Together (春光乍泄 chūnguāng zhà xiè), are all straight people.

Let’s move on to recent years, when we started to see more political protests, at least before COVID-19. Do you see these political events, such as the “Occupy Central” protests in 2014 and the anti-government demonstrations in 2019, as having any impact on local queer movies?

Leung: The thriving local, independent, and experimental scene of queer cinema would not attract a mass audience. But more recently, they started to garner local audiences, due to the resurgence of localism and the rise of yellow wave that prompted popular support of local films.

I therefore believe these movies will achieve more success. At the same time, there is a lot of nostalgia going on right now. Hong Kong Heritage Museum, a mainstream institution run by the government, organized an exhibition this year to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the death of Leslie Cheung. A key item being displayed in the exhibition is the pair of red high heel shoes that Cheung wore in the above-mentioned “Red” concert tour. Of course, the museum doesn’t describe it as a queer symbol or introduce him as gay, but…

But when you see a pair of red high heels being displayed to commemorate a male celebrity, that means something.

Leung: Right? They wouldn’t shy away from his queerness either. During the 1970s and 1980s, there were three Canton-pop male superstars, including Leslie Cheung, who were gay but not out. The other two were Roman Tam (谭百先 Tán Bǎixiān) and Danny Chan (陈百强 Chén Bǎiqiáng). Tam was famous for his extremely queer aesthetics on stage. He has a song called “Persian Cat,” where he dresses up like a cat. It’s so camp and everybody knows it.

Now they are all dead, and I see them being revered retrospectively, showing a nostalgia for the “golden era” of Hong Kong popular culture when its global influence reached a peak. With the rising localist and nostalgic sentiment, those queer undercurrents are being remembered and re-displayed.

This is an inspiring reminder of how queer culture is always a significant component of Hong Kong’s popular culture. My last question is about the influence of the National Security Law, which was passed in 2020 and has since then prompted wide public discussions over the tightened control brought out by the law. If the lack of censorship in Hong Kong over LGBTQ content is an important factor that enables queer cinema to thrive in the city, will this be changed by the law?

Leung: Most of the discussions I have heard are concerned with the ambiguity of the law, its blurred definition over what is allowed and what is not. Similar worries also pervade the film industry, as film censorship regulation needs to be revised to comply with the law. The media platform Intium did an interview with several young filmmakers that captures their ambivalent feelings: What can I say? What can’t I say?

But I also believe that constraints can lead to creativity. Another phenomenon that I find interesting is that, while all the independent filmmakers we have talked about are gay men, queer women are exploring other forms of creativity. The artistic works by Anson Mak (麦海珊 Mài Hǎishān) exemplify this shift. A very out queer artist in the 1990s and 2000s, Mak was one of the first people to talk about bisexuality in Hong Kong, and her early films were mostly related to the issue of sexual identity. But her latest project turns to the emotion of fear amid political protests and the time of uncertainty. While queer artists like Mak are not making “queer films” in a narrow, identitarian sense, their engagements with other political issues are still queer, if we see queerness as going against normativity.

Other LGBTQ stories:

Hong Kong: Court orders legal framework for same-sex unions (BBC)

In response to a legal challenge launched by activist Jimmy Sham, Hong Kong’s Court of Final Appeal refused to recognize same-sex marriage, but judged that the city had failed to provide alternative options for same-sex unions. The court requires the government to form an official framework within two years.

China’s LGBTQ tourists flock to Thailand to be themselves (SCMP)

While Chinese LGBTQ people feel ostracized and scorned in their home country, they find a sense of inclusion and empowerment via tourist trips in Thailand, a country that brands itself as friendly to LGBTQ tourists.

Queer China is our fortnightly roundup of news and stories related to China’s sexual and gender minority population.