The one and many ways of being Chinese

Although I possess only a Canadian passport, people in China have never made me feel like an outsider during my time as a foreign correspondent in Beijing and traveler throughout the country. After all, I was born in Hong Kong. Pro-independence activists in the city would disagree, but when I’m living in mainland China, I’m one of them – if I follow certain rules about being Chinese, a couple of which are particularly important.

One: There is no disrespecting your ancestors by forgetting your mother tongue.

Two: You need to consume intense amounts of food.

In both cases, I’m almost there but haven’t quite hit the mark.

Most foreigners can manage to impress locals by knowing just a few Chinese phrases, but if you are a huayi (a foreign citizen of Chinese origin), you might encounter some unpleasant experiences in the country if you do not have the language firmly under control. Take the observations of my huayi Australian friend: He says Chinese people stare at him like he has sprouted horns when they realize he doesn’t understand what they are saying.

But which version of Chinese are they speaking?

As any traveler in China notices, the country is home to numerous languages. A woman in northern Hebei Province speaking in the dialect unique to her region would struggle to communicate with anyone bound to the dialect of Sichuan Province in the southwest. I am fluent in Cantonese, which is spoken in southern Guangdong Province, Hong Kong, Macau and in many overseas communities, but it wasn’t much help when I was learning Mandarin. After studying for five years, I was able to understand that language well by the time I moved to Beijing, but speaking it still felt unnatural. Once I asked for takeout food in Mandarin at a Beijing restaurant and had to shout the same two syllables of the word in different combinations of rising, falling, rounded and flat pitches many times before the servers understood.

This happens despite all of us being considered members of the same ethnic group known as Han Chinese, a dubious classification encompassing roughly 90 percent of China’s population. The 55 other ethnic groups in China also have different languages, religious beliefs and traditions. While the government officially recognizes those groups, it has been criticized for carefully corralling their cultures.

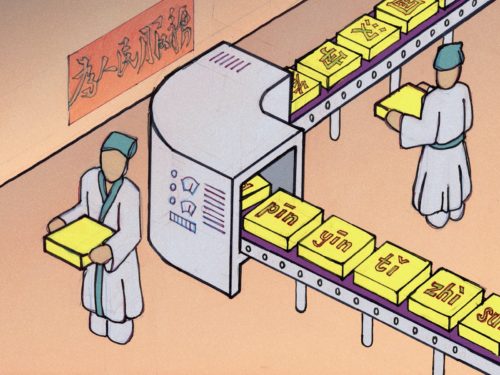

It’s no easy task creating a simple definition of a complex country. Still, in 1956, the Communist Party took on the language piece of that puzzle by establishing the country’s official language, Mandarin or Putonghua. The Beijing dialect was chosen as the norm for pronunciation; vocabulary would be built from various dialects; writing came from a simplified literary style pioneered by turn of-the-century authors.

Despite these steps, China’s Education Ministry estimates that 30 percent of Chinese citizens still do not speak the common language. In some places, there is active resistance against the pressure to speak Mandarin, such as when a government move to sideline Cantonese-language television programs in Guangdong Province sparked rare street protests in 2010.

I know a bit of what struggles with language feel like.

Last spring, I bonded over the difficulty of speaking Mandarin with people from Hainan, a tropical island province of China that resembles Hawaii or Bali. It could not be any more different than sprawling, smoggy Beijing.

My skin got roasted during my first day on the beaches of Sanya, and I found shelter from the sun in the shade of a palm tree on a near-empty stretch of sand. A group of women selling fruit walked over, along with men who drove Jet Skis for tourists. Hearing their local dialect, I was fascinated by its similarity to colloquial Cantonese.

We ended up conversing in Mandarin, and while none of us were hitting all of the sounds just right, we understood one another perfectly. When they found out I was traveling alone, they applauded my bravery and said I had to join them for dinner.

This was when I had to bring up the awkward fact that I am a vegetarian. Like many Chinese, they were horrified at first. But when they saw that I had a hearty appetite in spite of my “unfortunate condition,” they seemed less concerned.

That night they took me to a huge outdoor food court where each cook served throngs of customers around powerful portable stoves. Dishes of pork, fish, eggplant, cauliflower and leafy green vegetables were brought to the table in piping-hot clay pots, topped off with heaping bowls of rice. After the women changed into party dresses, we went to a karaoke bar and downed slim glasses of weak beer in a room with mirrored panels and disco lights – spending more time on playing drinking games than singing.

Then more meals.

The night ended with us choosing from fresh shrimp and mackerel laid out on sidewalks facing the shore. A nearby restaurant fried the food to everyone’s liking, while I ate kebabs of spicy mixed vegetables from a barbecue stall. We sleepily finished those dishes, then one of the Jet Ski drivers took us home, using shortcuts through construction sites and narrow dirt paths.

The next day, there was more to eat.

We munched on fried sesame balls and drank from heavy whole coconuts as we walked around a Buddhist temple and garden before going back to the beach. We peeled mangoes while lounging on hammocks, then went for a swim through the choppy waves. When I worried about not having a towel, the Jet Ski drivers showed me how to dry off by lying perfectly still on the sand after getting out of the water.

By sunset, I had adopted a new style of being Chinese: stress-free, imperfections and all. It didn’t bother me that I wasn’t a master of officially mandated Mandarin, nor was I worried that the government tried to classify me as Han when it didn’t feel like a fair fit. While both could be seen as tools of government repression, they had a lighter side: They were an attempt, crude or not, to bring together a nation of complex diversity. And if they failed in that mission, there was another universal language I and countless other Chinese could use to connect and communicate: food.

Custom illustration: Julia Yellow