Through the lens of American journalism, writer gets a new perspective on telling China’s story

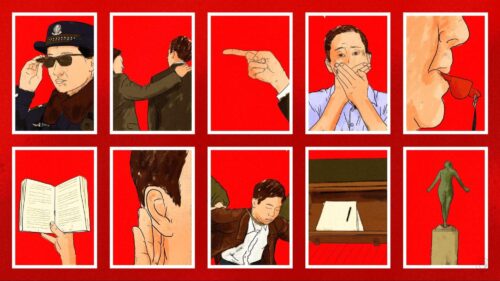

The United States and its justice-seeking brand of news gave a Chinese journalist a new understanding of her home country along with worries about telling a fuller story of China amid the media industry's struggles and the government's aggressive censorship.

Growing up in China, I never saw a protest, not even a small one. I don’t recall reading about any contemporary contentious demonstrations in my home country either — not in history books we had at school, not in a newspaper.

A few months after I came to New York to study journalism at Columbia University, I covered one.

Hundreds of people had gathered in downtown Manhattan after a grand jury chose not to indict an officer in the case of Eric Garner, an unarmed black man who died after being choked and restrained during an arrest. Among them was a serious-looking young woman who held a sign that read “White silence equals violence.” A middle-aged man raised another: “Now who do you call when a cop kills?” Their anger was palpable and powerful.

The event was one of many in an educational and professional experience as a journalist that reframed my understanding of the country I come from — and left me wondering how China’s stories will be told amid economic and political pressures in my industry, even while the nation’s rise commands more of the world’s attention.

China is not the best incubator for budding journalists. It wasn’t even a career I wanted to pursue when I was a kid, despite my father’s avid consumption of the news. Back then, nothing on the front pages of the state-run daily newspapers, filled with photos and articles about Communist Party officials attending meetings, inspired me.

I wanted stories that moved me, taught me something new and gave me intimate insight into what it means to be human. These are the type of tales I read in literature from authors whose careers inspired me to practice journalism — greats like Ernest Hemingway, Joan Didion, Nora Ephron and Susan Orlean. Their unassuming writing gave voice to the voiceless and revealed extraordinary truths about society and the individuals in it. These accomplishments would be impossible if the writers were bound by the restrictions permeating Chinese journalism today: A story must resonate with “positive energy” and pose no threat to the government’s authority.

Such boundaries meant there were no articles about the city regulators who chased and beat unauthorized peddlers in my home city. Few if any stories were told about the migrant laborers I saw squatting on dusty street corners, eating bowls of plain rice and pickles between bouts of heavy construction work. They were building China’s metropolises but received little respect or even due payment. Social justice — a pillar of American journalism — was mostly off-limits for the press in China.

It took leaving for me to fully understand this — that it was the core job of journalists to address injustice and suffering to inspire understanding and, in some cases, real changes. In the United States, challenging the powerful and telling the stories of the disenfranchised are an inherent and inspiring part of the profession, but they’re ideas that can’t be taken for granted in my country.

There is no Chinese example of heroic reporters tearing down the elite. We have no Woodward and Bernstein exposing a president’s misdeeds. Those who try are often silenced. Yang Jisheng, a 75-year-old journalist, was prohibited from traveling to the United States to accept an award at Harvard University for his book, “Tombstone,” in which he estimates that Mao’s government policies led to 36 million deaths during the Great Famine.

Such books fill the missing pieces of China’s history. Yet at this point, “stability maintenance” is a higher priority for the government than ensuring the fullest telling of the country’s past. Its propaganda arm pressures media outlets to pump out positive stories, while the country’s censorship apparatus — kicked into overdrive under the leadership of Xi Jinping — quashes certain information and fundamentally damages journalism by generating a misunderstanding and mistrust of its practice, goals and role in society.

For some journalists working in China, the concerns are more prosaic. Young reporters are quitting the industry not just in response to tight limits on what they can say but also because of economic concerns — the traditional media there, like others around the world, are struggling to adapt to the digital era. Salaries aren’t great. Some of my friends who are lucky enough to have staff jobs at respectable outlets say they can’t afford a comfortable life, let alone to expect to raise a family, in major cities that become more and more expensive at a breakneck pace.

A Guardian article describing young journalists’ plight resonated for many of my fellow graduates. In particular, they referenced a quote from the piece that attempted to make the best of censorship: “It’s just like a person has 10 fingers. There is one finger you can’t use but the other nine all work. There is one story you can’t write but there are still nine others you can.”

That may be reassuring, but how can anyone set out to speak truth to power if one of their main concerns is to avoid upsetting someone? And there may be a lot more powerful people who need to be upset in China’s future. The country’s role on the global stage has dramatically expanded. It has the world’s second-largest economy. All eyes are on the nation as its influence stretches across continents.

Someone needs to track the ebb and flow of the power wielded by the country’s decision makers, but the stories don’t stop there. There is another side to the vast attention now trained upon the country: People around the world want to read more than the usual headlines. They want to know about the fear and love of the younger generation. They want to hear about China’s aging society and how its elderly will be cared for. Only by documenting these and the many other stories like them will the full picture of the country be seen.

But there are many daily struggles my fellow journalists must manage amid these idealistic goals. They’re fatigued. To serve the digital era’s demand for page views and website traffic, they spend hours aggregating and rewriting other people’s work rather than having the luxury of authoring their own. They navigate increasingly precarious passageways of censorship at their state media jobs. The stories they do write are copied and pasted all over Chinese websites with no proper credits. Arranging a visa to the United States, where they might enjoy more freedom to produce what they want, is an extremely complicated, frustrating and months-long process.

Some of them told me they might get another degree or go into a different business. None see themselves doing what they are doing now in the long-term future, yet they still get energized when when talking about their favorite projects — whether a profile of the Dalai Lama’s brother, a feature about baijiu in American bars, or an explanatory piece on environmental justice in the Bronx. My own article on Chinese students converting to Christianity in the U.S. showed me the power of a reported story to reveal the forces shaking and shaping individuals and societies.

Will such small doses of excitement and passion be enough to keep us pushing through the years to come? In the long run, I really don’t know. Journalism is changing. China is changing. So are we. For now, I just want to focus on one small act of journalism at a time and see where the stories take me.

Note to readers: What role will journalism play in telling China’s story? Share your thoughts with us at editors@thechinaproject.com.