Q&A with Zing Bai, the founder of a New York restaurant who wants to take her ‘awesome’ fried rice across the U.S.

Haijing "Zing" Bai, the founder of Zing's Awesome Rice, discusses her successful restaurant in New York, her life prior to becoming an entrepreneur in the city’s competitive food industry, American ideas about fried rice and her plans to expand the business.

Last summer, Haijing “Zing” Bai’s parents in Beijing had no idea their daughter had quit her law firm job in New York and they were telling her, as they did during every weekly call, how proud they were of her career.

“People say, ‘Don’t ask for permission, ask for forgiveness,’ so that’s what I did,” said the 36-year-old founder of Zing’s Awesome Rice on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. “I know they are very proud of me.”

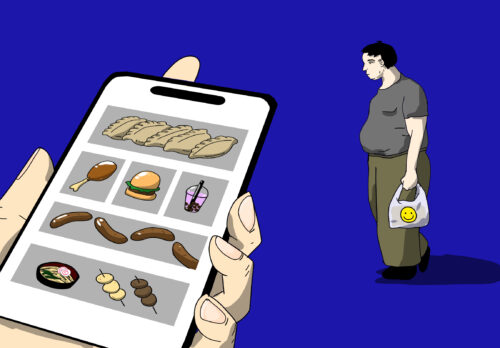

Since Awesome Rice launched last November, the 400-square-foot open-kitchen spot has become a neighborhood favorite and has received media coverage that includes positive reviews by The New York Times and NBC News. Plus, it is breaking even. It achieved this by serving one core product: a 26-ounce, 700-calorie serving of fried rice made with a touch of olive oil, protein and vegetable of choice.

“It’s very balanced,” she said. “I think we got very lucky that people like the product and people like the place.”

Since coming to the United States for college in 1998, Bai has been involved in many fields outside the food industry. She has tutored piano, administered the Test of English as a Foreign Language, been an executive assistant at a real estate agency, worked at Teavana, traveled all over America during a three-month stint as a flight attendant and interned at the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Along the way, she picked up an MBA from Hawaii Pacific University and a J.D. with distinction from Cornell.

Oh, and she published her first novel, an urban romance about young Chinese finding their place in American society, on Amazon in May.

Bai, born and raised in Beijing, attributes her creativity to her father. She said he almost never cooks the same thing twice and went out of his way to expose her to different cuisines. Once, when she was eight years old, he insisted that she sip a beer from the first German brewery that opened in Beijing because it was “so cool.”

Looking ahead, Bai wants to bring her Chinese dishes to diners all over the United States, much like Japanese ramen has spread into cities around the nation. She spoke with The China Project about that dream, how she began her journey as a restaurateur and her busy life outside of Awesome Rice.

The China Project: How did you end up in the United States?

Bai: I came here in 1998. Some American college recruiter came to my high school, Beijing No. 4 High School. I was successfully recruited, so I came to the U.S. for college. I majored in business, and after that I got my MBA from the same college where I got my undergrad degree [Hawaii Pacific University]. I worked in business, management, logistics, food and the beverage industry for a while before I went to law school, and practiced law to the point I decided to open this shop.

The China Project: Why did you go to law school?

Bai: I wanted to expand my horizons. I grew up in China, and all my education was more business-y stuff, so I feel the law school experience filled me in with lots of history, politics and legal background of the United States.

The China Project: How did you go from working in a law firm to running your own restaurant?

Bai: I know many lawyers or ex-lawyers who left firms to do all kinds of exciting, different things — making cupcakes, selling fashion products, for example. But mostly I heard that they hated being a lawyer, so they left. It’s a completely different story for me. I loved being a lawyer. I really enjoyed it. It was giving up something that I loved to do … for something that’s completely new.

The China Project: When did you get the idea to open your own restaurant?

Bai: Probably spring 2013. I often host dinner parties, brunch parties. Many of my friends were impressed by both the taste and the presentation and quality control of the food. They said, “Oh, you should open a restaurant.” When I’d heard that 18 times, I started to seriously think about it. I thought, “Wait a minute, do Americans necessarily understand fried rice?”

The China Project: What worries did you have launching the business?

Bai: Owning a business is having an infant baby. Anything could happen. I do have the confidence in the concept and in myself as a person, together with my team. We will be able to handle any emergency, but still I have fear for any emergency.

The China Project: What style of Chinese food do you like the most?

Bai: I probably like every cuisine for its uniqueness, and also I like many kinds of different fusion foods. I’m a big foodie. I’m a big fan of everyday Cantonese food. I think the Cantonese have a great culinary culture, from their everyday congee stuff, dim sum, to the high-end seafood. It’s one cuisine that can be so inclusive and so sophisticated.

The China Project: What is important to you about Chinese food?

Bai: What I love about Chinese food in general is, first, the homey feeling to it. For example, my dad is not a chef but he is very good and very passionate about cooking. Cooking to him was a way to express his love to his family, although he was very busy when I was a kid. Maybe once a month … he would cook us this elaborate meal. From a very young age, I connected food and cooking for people as a way to express love. That’s one thing I think of Chinese food. It’s love. It’s very warm. Another thing about Chinese food is it’s just such a free and rich style. We use steaming, searing, frying, deep-frying … all kinds of cooking methods and such a large range of ingredients.

The China Project: What is one of your favorite dishes that your dad makes?

Bai: My dad’s fried rice. It’s so addictive, although it’s not the healthiest thing. That’s why I changed his method. Sorry, Dad. He uses way too much oil. I cut like 99 percent of his oil — just a little dash of olive oil to be heart-healthy. I really liked his Xi’an cold noodle (凉皮). It’s also gluten-free. My dad is from Xi’an, so his cold noodle is very, very good.

The China Project: What was your first impression of food in America?

Bai: Food-wise, I actually never had a cultural shock. My dad purposely exposed me to many different types of cuisines growing up in China. I remember when the first German beer hall opened in 1988 in Beijing, my dad took me there. He even let me drink draft beer. I was eight. My dad was like, “Oh, this is something so cool, German brewery beer, let’s go try it out.” My dad is such a foodie. When I came to the U.S., a sandwich was not an unfamiliar thing. I’d had pizza before. So it was rather easy on me. Secondly, I was in places that offered both pretty decent Asian food as well as Western food. I didn’t feel I was forced to eat only one type of thing.

The China Project: What is your impression of the American understanding of fried rice?

Bai: They would probably say, “Oh, frozen beans in there, overnight char siu [Cantonese barbecue pork], some leftover rice, should cost two dollars.” But that shouldn’t be the way. I think Asian people would picture fried rice so differently. We wouldn’t regard the Chinese takeout version of fried rice to be real fried rice. Don’t get me wrong: I’m a fan, to certain extent, of Chinese takeout food. But I would never order fried rice from a Chinese takeout place because it really can’t compare to what fried rice, a Chinese staple, could be. I want to educate the foodies and everyone here in the North American market on what good fried rice should be. Not even to say what authentic, Chinese fried rice should be but just how can we make healthy, modern, nutritious, balanced and yummy fried rice. Twenty years ago there was no such a thing as ramen, but now it’s a household American thing. Fried rice could be the next ramen.

The China Project: What is the next step you’re considering for the expansion of Zing’s Awesome Rice?

Bai: We want to stabilize operations and grow up here first. I’m starting the research and talking to industry veterans. I’ve been looking at locations in Midtown and Financial District.

The China Project: What do you think about Chinese food in New York City?

Bai: There is pretty good Sichuan food, Cantonese food. Pretty good Shanghainese food, too. But we are missing lots of northern Chinese food and also these daily, homey foods, such as the northern style of congee. And because of the great success of Chinese takeout-style food — Americanized Chinese food — Americans may not be even aware that they are missing a lot.

The China Project: How has opening this restaurant influenced your perspective on China, the U.S. and the relation between the two?

Bai: This experience makes me embrace my Chinese roots even more. I feel I’m doing a job as an ambassador of Chinese culture, or at least partial Chinese culture, because this is fusion. And having this restaurant actually gave me time to write and finish my book, which is my first Chinese fiction writing.

The China Project: What is your connection to China at this point in your life?

Bai: I am Chinese, and I will always be a Chinese — regardless of my citizenship. I feel there is this deep root and connection between me and China as a country and a culture. Many of my sentiments, literature preferences, cooking skills and ingredient selections — these things cannot be separated from my Chinese roots and Chinese background. I’m very lucky that I have this Chinese leg and I have this American or international leg.

The China Project: How will you be involved with China in the future?

Bai: I have a few high school friends who reached out to me to ask if I want to bring my brand to China — maybe have a chain store. I’m very positive about the future opportunity to bring Zing’s Awesome Rice to China.

The China Project: What is something that you think people misunderstand but is important to know about China?

Bai: I think it’s important for people here to understand that China is a huge and very diverse place. Like here: American culture, Midwestern culture and New Orleans culture, Long Island, Maine — it’s completely different. So when you think about China: Xi’an, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Fujian, Xinjiang. So diverse. So different.

The China Project: What is your book, Love, etc., about, and what has been your experience as an author?

Bai: It is based on a new immigrant like myself and my friends, who were born in China, came to this country as foreign students and absorbed the culture here, and find their place in society as young professionals, as entrepreneurs. It’s heavily about romance and love, but also touches upon immigrant life and career.

The China Project: Why do you quote Chinese poetry in the book?

Bai: I’m a big fan of Chinese ancient literature, including Tang poems, the Song Dynasty lyrics and poems. And also lots of new age Chinese writers.

The China Project: Who is your favorite Chinese writer?

Bai: Feng Tang, from mainland China, who is the chairman of one of the biggest Chinese investment banks and also an ex-McKinsey partner. Unfortunately, Chen Zhongshi just passed away. He is very, very well-regarded, and one of my favorite writers.

The China Project: Who is your favorite musician?

Bai: Yo-Yo Ma.

The China Project: What is your favorite movie?

Bai: I like early Wong Kar-wai, basically everything up to 2014. Zhou Xingchi [Stephen Chow] is pure awesomeness, but I haven’t seen his latest movie yet.

The China Project: What is your favorite food?

Bai: Other than Zing’s Awesome Rice, my dad’s cooking, because his cooking is so diverse and full of creativity.