Vegans in China

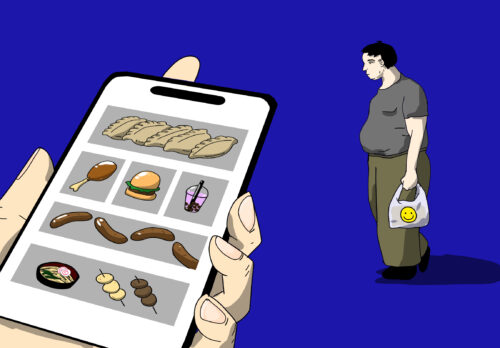

Demand for meat is at an all-time high in China, but there is a growing movement to follow plant-based diets.

Housed under the sloping golden roofs of Shanghai’s Jing’an Temple, the banquet hall filled quickly. Big families arrived en masse, towing children and grandparents; old friends waved to each other across the room, making their way through the crowds hunting for their tables, to greet one another. Volunteers at the door asked each new entrant to dab their finger in green paint and press it down on a piece of paper — the simple tree trunk drawn on that page quickly grew hundreds of leaves. As the dinner hour neared, all of the 400-something chairs were full and children had to be pulled onto laps to accommodate latecomers.

Old and young, the guests at this annual dinner organized by the Shanghai-based organization Veggie Dorm (素社 sù shè) had come together to enjoy a vegan meal of soy-made “meats,” vegetables, and mushrooms, and to celebrate a lifestyle that they follow or aspire to follow. They are part of a growing number of Chinese choosing to avoid eating animal products.

“People used think of vegan as a Buddhist thing, but now, you can see there are many young people making this choice,” says Jacqueline Yao, a student of Chinese traditional medicine, looking around the banquet hall.

The choices of vegetarians and vegans in China stand in contrast to their country’s appetite for meat: China now eats and produces roughly half the world’s pork, while poultry- and beef-heavy Western fast-food chains metastasize throughout the country. But the size of the Veggie Dorm dinner is an indication that vegan and vegetarian lifestyles are becoming more and more mainstream.

“We can save a lot of energy and we can protect our environment, but if we eat more meat, we will pollute our air,” says Joy Pan, a human resources manager from Shanghai, who became vegetarian in 2009. “More and more people are acknowledging the tough situation around us; many of my friends and I also share the information we know with others.”

Food safety is another concern driving Chinese to give up meat. This was the case for Lawrence Feng, a 28-year-old translator from Henan Province, who says, “The bird flu and the dead pigs in the river were the catalyst for me to make this decision.” He is referring to two incidents in 2013: one, a poultry-eating warning based on an outbreak of H7N9 flu; the other, a highly publicized scandal in which a farm dumped diseased pigs into tributaries to the Huangpu River, which traverses Shanghai. “I was thinking at that time, why do I have to listen to what the media says about what to eat?”

While meat is now considered a staple in China, heavy, widespread consumption of it is a relatively recent phenomenon. Prior to the economic opening up of the country in the early 1980s, meat was a luxury item that the majority of Chinese could not regularly afford, according to University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill professor Barry Popkin, who is the U.S. coordinator of the longitudinal China Health and Nutrition Survey. But as incomes rose, Popkin says, the desire for meat, paired with the introduction of Western diet culture, greatly increased the average person’s consumption of animal products.

That means that China’s vegans and vegetarians are often breaking with family habits and pushing back against a prevailing belief that meat is necessary for a healthy diet.

For Ph.D. candidate May Mei, 26, avoiding meat while at her parents’ home in Henan Province is difficult, but a lack of vegan options on her university campus has bonded her more tightly with a group of like-minded students. “We have about 16 students who are vegan or want to be vegan in East China Normal University,” she says. “We have a WeChat group where we talk about veganism. About one or two times a month we have a meeting, or we will find some new places to eat.”

Zoe Gu, 26, a research analyst in Shanghai, says it’s hard to connect with other vegans. And although her decision to become vegan is linked to Buddhist beliefs that she shares with her family, she still receives some resistance to her diet. She occasionally caves in to family pressure to share meat dishes or has to negotiate with friends who don’t understand her values while ordering at large dinners. “You know, Chinese food,” she says, referring to the added difficulty of family-style servings for a vegetarian.

But Gu adds that those around her have become more accepting over the three years since she made her choice. “Many of my friends even try to be a vegetarian some days a month,” she says.

Veganism and vegetarianism are still far from being accepted as mainstream in China, but the past five years have seen growth in the visibility of the movement. A fledgling network of Chinese-run vegetarian organizations, particularly in China’s three major cities, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Beijing, have become points of connection and platforms for education. WeChat and Sina Weibo interest groups have grown, becoming hubs for people to share information and recipes, and to find support from others who share their values. In May 2016, the Chinese Nutrition Society’s updated guidelines included a set of recommendations for vegans and vegetarians, the first time this category was included. In November 2016, Shanghai’s first Vegan Fiesta, a daylong festival, was attended by 2,500 people.

While the emerging trend links China to global vegetarian values of health and sustainability, diets that exclude animal products are far from being new to China. Special rituals around limited meat consumption were part of the Confucian teachings beginning in the fifth century B.C.E., while the Buddhist and Taoist traditions of ancient China called for followers to observe the diet of the temples — pure vegan with no garlic or onion.

These traditions, too, are part of the “new kind” of vegetarianism rising in China since the turn of the millennium, argues Wang Yahong, a sociology doctoral candidate at the University of Glasgow, originally from Hebei Province. Wang, who is writing her dissertation on vegetarianism in Beijing, says China’s rising vegetarianism is “a hybrid of the traditional Buddhist idea and the imported Western vegetarian ideas. They reinforce each other and find support in each other. It makes their argument more powerful, more strong.”

Business owners of classic Buddhist vegan restaurants are enjoying a boom from the conflation of the contemporary and traditional, according to Ding Hongyi, the 24-year-old owner of Xiang Ji Ge, a Buddhist vegan restaurant in Shanghai.

“Now there are a lot of environmental and health problems, so we realize that our traditional culture is right, and we eat vegan again,” says Ding, whose clientele encompasses Buddhist vegans, vegetarians, and people who observe meat-free days on the lunar calendar or just want a healthy meal.

This also rings true for Forrest Song, 31, the founder of Shanghai’s environmental and plant-based health education organization Veggie Dorm, which hosts the annual dinner along with roughly 100 other events each year. Song says that while his organization, started in 2012, focuses on global ideals, he believes some may discover a connection between their dietary ethics and Chinese traditions.

“Initially, it’s a vegan lifestyle that should be fun, healthy, green, and warmhearted. People like this kind of energy,” says Song, who left his job as a partner in a corporate training firm to focus on Veggie Dorm. “But when they adopt these good habits and they can connect them with the old knowledge about our culture, something can be related. When we are really changing our lifestyle, changing our diet, our mind will change.”