Accomplishing what they could not at home: The bond between American and Chinese women

From advocating together against foot binding to raising money for hospitals, John Pomfret recounts the history of extraordinary sisterhood across the Pacific.

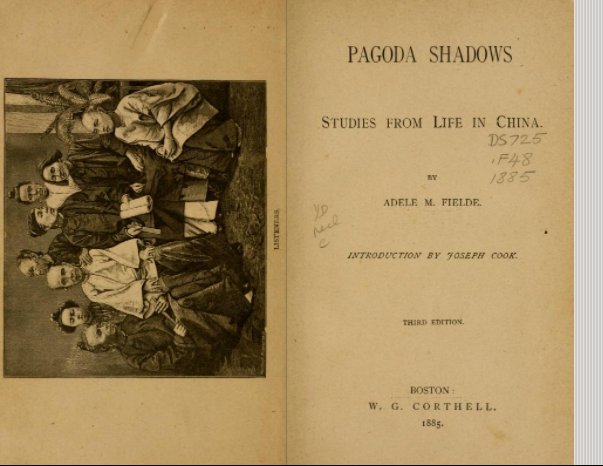

On a clear morning in May 1865, Adele Fielde landed in the British colony of Hong Kong after a stormy 149-day voyage on a tea ship from New York. A friend had squeezed Fielde, suffering from a high fever, into her wedding gown, and now she waited on deck for her fiancé, a Baptist missionary from New York named Cyrus Chilcott. The pair had gotten engaged in America, planned to reconnect in Hong Kong, marry, and then head to Bangkok to preach to Chinese migrants there.

A rowboat approached, but Chilcott was not on board. Fielde learned from the boatman that typhoid fever had struck down her fiancé several months earlier while she was in the middle of the Pacific. So Fielde now found herself, as she would write later, “in appalling desolation alone on the shores of Asia.” The ship’s captain advised her to return to the United States. She set out for Bangkok instead as one of the first single women to work as a missionary in Asia.

After several years in Bangkok, Fielde moved to a Baptist mission in Shantou, about 250 miles (400 kilometers) up the coast from Hong Kong. There she founded a school, The Path of Brightness, which constituted the first formal literacy program for women in modern Chinese history. She led a wave of American women who traveled to China as conveyors of values, builders of institutions, and symbols in a changing China. Calling her students “Bible women,” Fielde broadened the curriculum to include hygiene, child care, basic medical skills, and geography so that her missionary work began to resemble less an evangelical enterprise than an early version of the Peace Corps.

A farmer’s daughter, born in 1839 in upstate New York, Fielde grew up in a time when the great social and feminist issues of the 19th century were rousing a generation. Women in the North had battled slavery, and after the Civil War, they demanded opportunities. Women’s colleges opened. By the time Fielde was 25, she herself was the principal of a girls’ school. Because of Fielde and pioneers like her, the American missionary endeavor in Asia and particularly in China became a profoundly feminine one. Women, especially single women, would soon make up the largest share of American missionaries overseas.

Freedom and opportunity in China

Fielde’s story illustrates the powerful ties that continue to bind Chinese and American women to this day. To Fielde and other pioneers like her, China offered freedom and opportunity at a time when educated American women faced limited career options at home. American women were surgeons in China when they were denied entry into operating rooms in America. They chaired university departments when only a few of them were teaching at the college level in the United States. They ran Christian missions with scores of employees when few of them could get management positions in the United States.

Fielde and her American sisters also started a tradition of spearheading the extraordinary advances made by women in China. Fielde’s generation helped unchain Chinese women from the home and attacked foot binding, contributing to the single biggest human rights advance in modern Chinese history. American missionaries took the lead in educating Chinese girls and in providing them with role models for a new kind of life. Fielde and her American sisters fought female infanticide, setting out baskets beside lakes with a note that read: “Place your babies here. Do not throw them into the pond.”

American women missionaries also showed Chinese women that there was more to life than having babies. Although American female missionaries were supposed to be priming their Chinese charges for a life of marital bliss with a Christian husband, the message became muddled because so many of the Americans, like Fielde, remained single themselves. As such, their Chinese sisters modeled themselves on what their American teachers, doctors, and adoptive mothers did, not what they said. In 1919, the entire inaugural graduating class of Jinling Women’s College of Arts and Sciences, an American-funded missionary school in Nanjing and the first university in China to grant bachelor’s degrees to women, took an oath not to marry. “I loved to be alone, it was in general the attitude of the woman of our time,” wrote Xu Yizhen 徐亦蓁, a member of that first class.

To be sure, women from other countries vied for influence in China: anarchists from Russia, revolutionaries from France. But none could match the Americans in number or influence. Americans defined what it meant to be a “new woman” on the cusp of a new century. Americans barged into China’s classrooms, hospitals, kitchens, and bedrooms to fashion what Baptist missionary leader Lucy Waterbury Peabody called “a new woman abroad.”

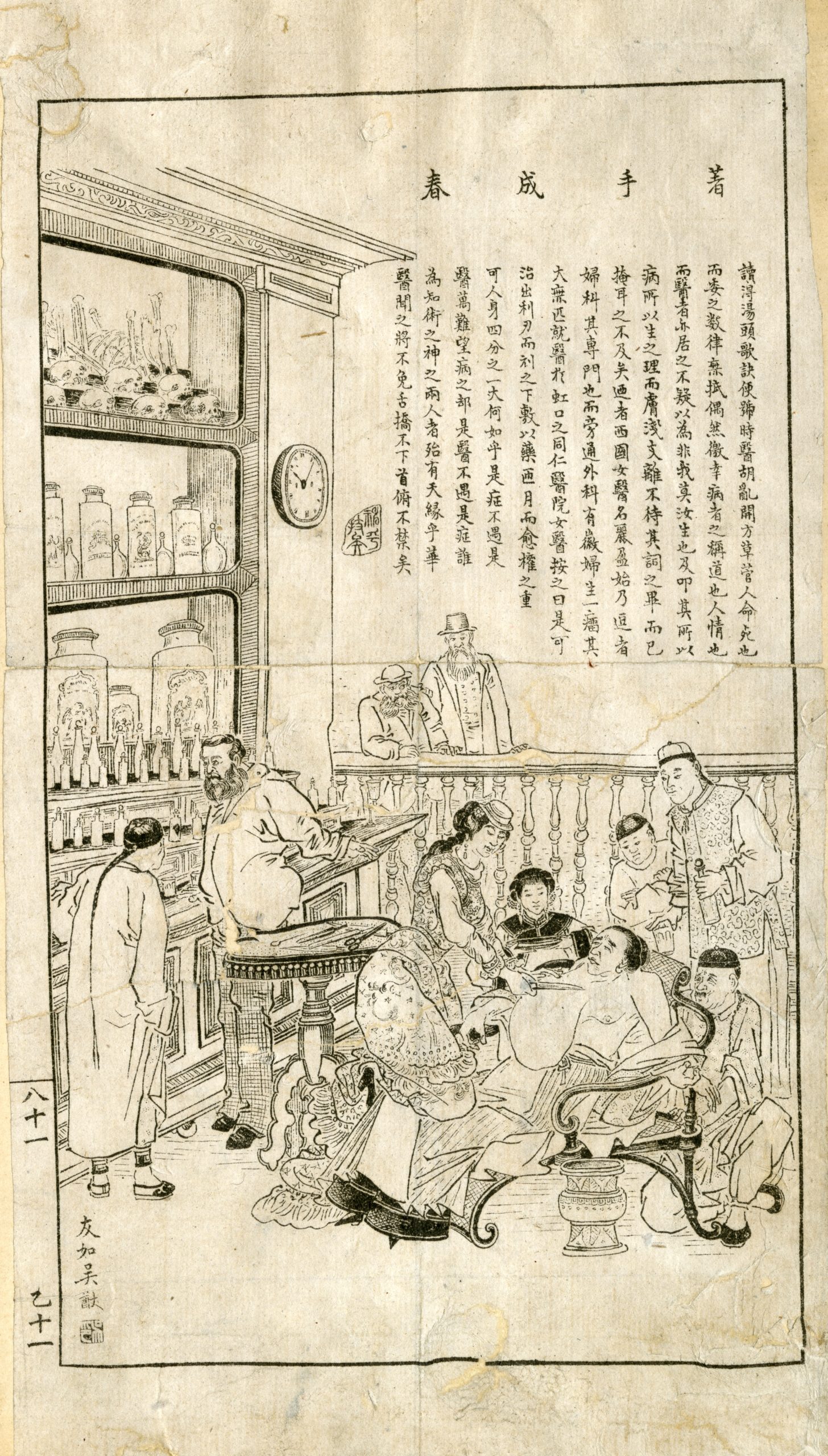

Returning to the U.S. on vacation in the 1870s and 1880s, Adele Fielde was a huge hit in churches nationwide. Her open letters to American churches were so popular that they were collected in a book called Pagoda Shadows, published in 1884. The first edition sold out in a week, and it went through six printings. In it, Fielde described Chinese dress, weddings, festivals, funerals, and medicine. She referred repeatedly to the low regard in which Chinese society held its women; the torture of foot binding; how Chinese women became property when they married; and how they obtained power in the family only by bearing sons. Fielde surveyed 160 of her Bible women and found that they had personally killed 158 unwanted baby girls — and not a single boy.

There was nothing either obvious or inevitable about America’s abiding fascination with the Middle Kingdom, but American women were entranced by Fielde’s China, with its rich tableau of exotica and its universal humanity. Fielde had succeeded in her goal: to create a bond between American and Chinese women.

Of course, influence has never flown in only one direction. Chinese women moved their American sisters as well. In the 1910s, heated debates raged in the dormitories of Smith College and other American women’s universities over who was the greatest living woman: the social worker Jane Addams or the medical missionary Shi Meiyu 石美玉, known throughout the United States at the time as Mary Stone. Today, Mary Stone’s name has been all but forgotten, but for decades she moved seamlessly back and forth between the two countries, fundraising in America for her hospitals in China. Hundreds of Americans followed Stone to China to devote themselves to China’s cause.

China style — too hot for China

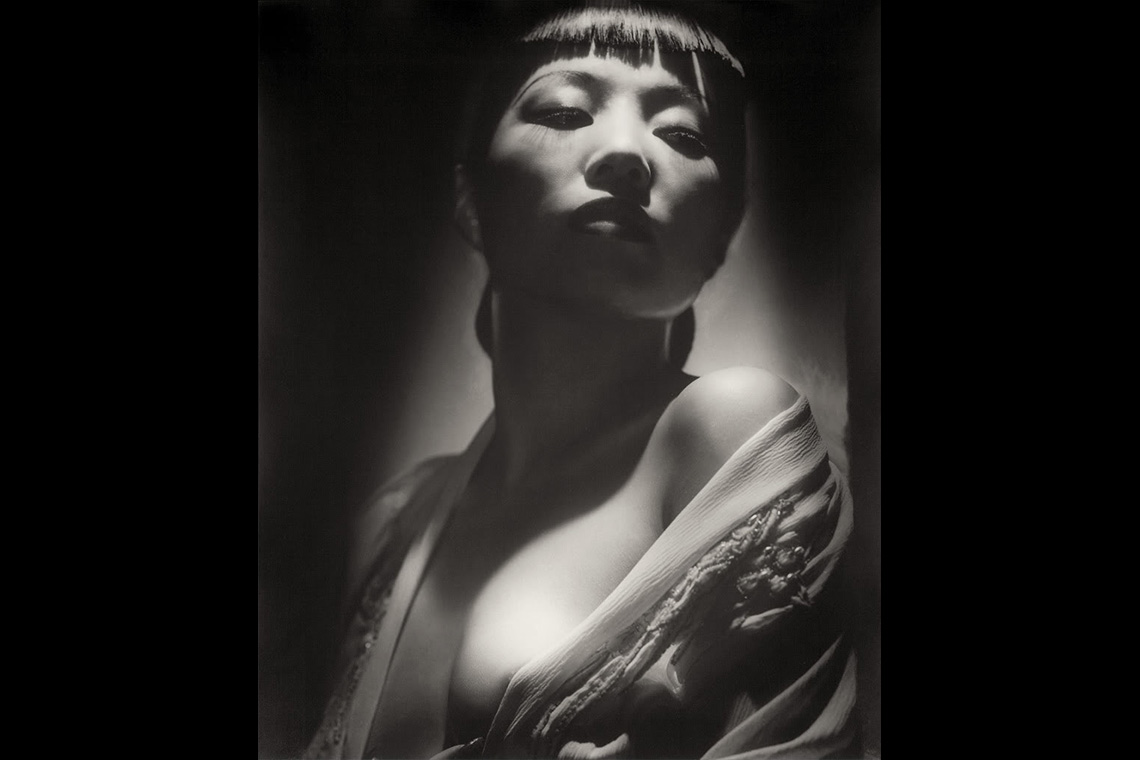

China’s appeal was expressed in other ways, too. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Chinese-American actress and laundryman’s daughter, Anna May Wong 黄柳霜, epitomized the style of the era. In 1934, the Mayfair Mannequin Society of New York named Wong the “world’s best-dressed woman.” She was the first star to sport bangs. Four years later, Look magazine called her the “world’s most beautiful Chinese girl.” Rumors of prodigious liaisons littered the gossip columns, but her most serious affair ran aground on a California law that prohibited whites and Asians from marrying. Nonetheless, in fertile U.S. soil, Anna May Wong planted a commanding image of a sexy, alluring, and powerful Asian woman.

In the country of her ancestors, Anna May Wong ignited conflicting emotions. When she visited China for the first time in February 1936, thousands flocked to the Shanghai docks and crowded along the Huangpu River to catch a glimpse of the American star. A month later in Hong Kong, a mob shouted, “Down with Anna May Wong, the stooge that disgraces China!”

Wong was too hot for the Confucianist prudes and the equally prissy Chinese left. Her star power defied traditional Chinese notions of propriety even as her beauty, talent, and charisma stirred her fans. Wong embodied the enticing mix of threat and appeal that America has always represented to the Chinese. Faced with a freewheeling American sex symbol, and an ethnically Chinese one at that, Chinese critics reacted with profound unease.

“One of the outstanding women of all the Earth”

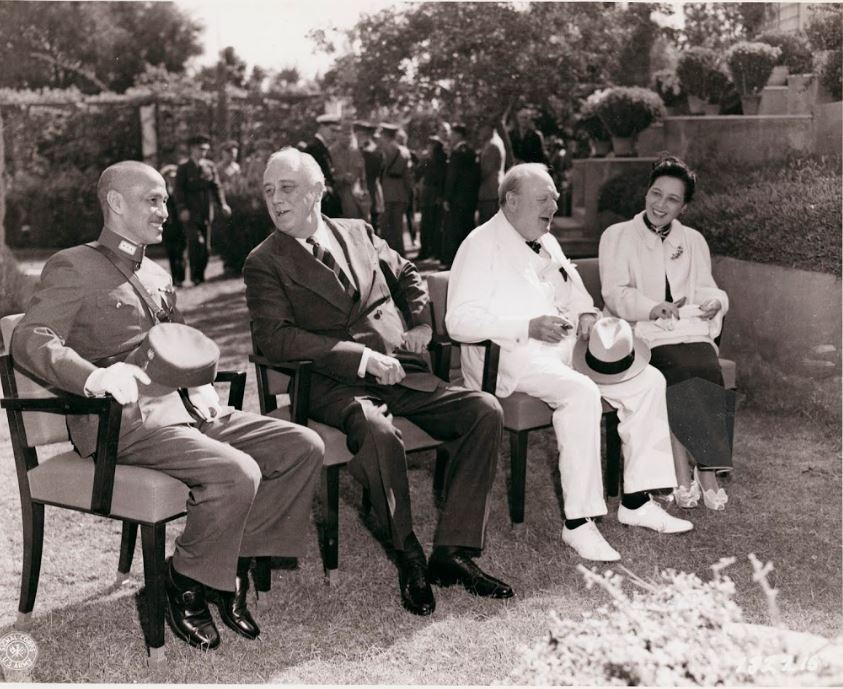

That mixture of glamor, sex appeal, and smarts found its ultimate embodiment in Soong Mayling 宋美龄, the wife of China’s leader Chiang Kai-shek. Soong Mayling defined China for generations of Americans. On February 18, 1943, at the height of the Second World War, Madame Chiang Kai-shek, as she was known, became the first private citizen and the first woman to address Congress. In the House, Texas congressman Sam Rayburn introduced her as “one of the outstanding women of all the Earth.” First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt told her diary that as she watched Mayling come down the aisle in the Senate, escorted by tall white politicians, she “could not help a great feeling of pride in her as a woman.” It was a deep illustration of the warp and woof that bound the U.S. to China: a Chinese woman, raised in Shanghai, educated in the Deep South and New England, then steeled in wartime Chongqing, returning to the United States to inspire American women. As Time magazine observed, “Tough guys melted.” One congressman said, “Goddam it…I never saw anything like it, Madame Chiang had me on the verge of bursting Into tears.”

Holding up half the sky

In the modern era, the cross-pollination between Chinese and American women has never stopped. In the 1960s, the American feminists drew inspiration from Chairman Mao Zedong’s aphorism that women “hold up half the sky” (妇女能顶半边天 fùnǚ néng dǐng bànbiāntiān) and modeled their consciousness-raising exercises on the “speak bitterness” campaigns used during China’s land reform movement in the 1950s. Once the two countries reopened communication in the 1970s, China continued to serve as a stage for American women. For years in the 1980s, Virginia Kamsky’s highly successful Beijing-based consulting firm hired mostly women. In 1995, Hillary Clinton’s speech to the UN International Women’s Conference resuscitated her political career. Clinton’s speech got a huge response from the delegates in Beijing. Women lined up for her to autograph copies of the address. A New York Times editorial declared that it “may have been her finest moment in public life.” Once again, China was the place where American women could accomplish things they could not at home.

Clinton’s speech resumed the tradition of mutual inspiration between American and Chinese women. One of the delegates at the International Women’s Conference was Guo Jianmei 郭建梅, who had been sent to cover Clinton’s speech for the All-China Women’s Federation. Sfhe looked at it as a task. But when she heard Clinton declare that “women’s rights are human rights,” she thought, “I have found a soul mate.” Clinton, Guo later told a Chinese interviewer, “shines with the light of wisdom, self-reliance, and self-confidence.” If Mother Teresa symbolizes “love,” Guo said, Hillary stood for “wisdom.” Inspired by the conference, Guo became a pioneering feminist and opened a legal-aid center for women in Beijing.

Of course, Clinton was not working alone. In the 1990s, Americans helped to resuscitate the women’s movement in China. Led by the Ford Foundation, Americans poured millions of dollars into projects for Chinese women. They bankrolled independent women’s organizations, a hotline for advice on sexual discrimination, a magazine for rural women, a sex-ed center for youth, and a women’s law center. Ford funded the translation into Chinese of the 1970s classic Our Bodies, Ourselves along with other feminist tomes.

The Feminist Five

Chinese women have also continued to stir their American counterparts. In March 2015, Chinese security officials expanded their assault on China’s nascent civil society to the women’s movement, detaining five women in three cities on suspicion of “picking quarrels.” The women, known as the Feminist Five, had planned to distribute leaflets and stickers on March 8, International Women’s Day, to protest groping on public transport, a widespread problem in China’s packed subways and buses. The Feminist Five represented a young, creative approach to women’s issues. All of them had studied how American feminists had organized campaigns in the U.S. And now, across America, thousands signed petitions calling for their release.