The split at the heart of Chinese America

Affirmative action used to be about black and white. But new Chinese immigrants have “scrambled that traditional thinking,” and clashed with the so-called Chinatown Chinese.

SAN FRANCISCO — Sean Chen moved to the United States in 1998 after graduating from Shanghai’s Fudan University, one of China’s best. The first student in his family to attend college, Sean recorded the fifth-highest score in his home province of Anhui on China’s notoriously difficult gaokao, or college entrance exam. In the U.S., Sean enrolled as a doctoral candidate at UCLA. Within a year, his wife had joined him. In 2002, he completed his Ph.D. and went to work on the development of advanced medical devices, first in northern California and then near Los Angeles. His innovations resulted in nearly a dozen patents. Two children followed along with a comfortable home near Rowland Heights in the eastern suburbs of LA.

Sean chose to live in the United States, he said, because it’s a melting pot. “It’s fascinating that people are from so many different cultural backgrounds,” he said, “and we are living here peacefully.”

For years in America, Sean lived the life of a striving and successful Chinese immigrant. He paid attention to politics — partly because of his deepening appreciation of the American system and his concern for his children’s future — but he never got involved. Until 2014.

That year, a California state senator named Edward Hernandez introduced a bill to amend the state constitution and lift the 1996 ban on the use of race in admissions at California’s public universities. State Constitutional Amendment 5, or SCA-5, sailed through the state senate in January 2014 and looked set to pass the assembly soon thereafter.

Sean and hundreds of other Chinese Americans like him saw SCA-5 as a direct attack on the educational prospects of their children. Since California had become the first state to do away with affirmative action in state college admissions in 1996, the prospects for Asian-American applicants at California’s best colleges had brightened. Since 1996, the entering class at California’s best state college, the University of California, Berkeley, has averaged above 40 percent Asian American while more than 35 percent of the UCLA undergraduate student body has been Asian American, too. Both of these are more than double the 15 percent share that Asian Americans comprise of California’s population. And now, Sean worried, an amendment to California’s constitution was going to reinsert race into state college admissions and take that all away.

Sean and his friends began organizing. They had an uphill fight. Practically all of the Asian-American politicians in California, members of a Democratic majority, had come out in favor of the constitutional change.

Sean and hundreds of Chinese immigrants held noisy protests; they surrounded the offices of one Chinese-American assemblyman until he emerged and renounced his support of the bill. Their agitation forced three Chinese-American state senators who had voted for the bill to switch their positions. Many of the protesters made campaign donations for the first time. Sean gave about $1,000 to a variety of candidates. Breaking with decades of Asian-American tradition, they began supporting Republicans.

We bring talent and money and our kids can’t go to school?

Social media played a key role in spreading the word. Sean began blogging at wenxuecity.com — a news and gossip website favored by native Chinese speakers in the United States. He gained thousands of followers. Just at this time, the WeChat communications app gained popularity among Chinese in America. WeChat’s owner, Tencent, tweaked its own rules and gave campaign organizers the ability to collect hundreds of people in chat supergroups of 500 or more. Ten chat supergroups were handed out to movement organizers and were used to organize Chinese voters. Haipei Shue, another Chinese-American organizer, remembers flying to Silicon Valley from Washington a few times within a few months to help advise Chinese immigrants on how to get involved in politics. “This was the beginning of a political earthquake,” Shue said.

While Chinese Americans had pushed back against racial quotas in the past, noted Oiyan Poon, a scholar of Asian-American issues at Loyola University Chicago, “SCA-5 was the rocket fuel and WeChat was the pipeline. It really set people off.”

Then on March 17, 2014, SCA-5 died in the state assembly. Later that year, Chinese-American opponents of the amendment got candidates elected to the state assembly and senate as well as to school boards in Chinese communities around the state. Lobbying groups such as the Silicon Valley Chinese Association and the Orange Club of California emerged as new centers of political power.

“So here we were, part of a new wave of immigrants — with strong educational backgrounds or very strong financial backgrounds,” recalled Sean. “We’re bringing our talents and money into this country and there’s going to be a law to limit our children going to school? How does that add up? We got pretty agitated. We started making noise.”

The noise Sean and his comrades made in California has resonated through Chinese-American communities across the United States, exposing a yawning gap between new Chinese immigrants mostly from mainland China and earlier generations of Chinese. Following SCA-5, new Chinese immigrants have continued their assault on affirmative action, bringing cases against Harvard University, Princeton, and the University of North Carolina, accusing all three of having higher standards for Asians than for applicants from other ethnic groups.

Along the way, these new immigrants have shaken the power structure of one of the most successful minority groups in the United States. And now, according to Richard Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at The Century Foundation, this movement is poised to have consequences for affirmative action nationwide. “People used to think of affirmative action as a black and white issue,” he said. “But Chinese Americans have scrambled that traditional thinking.”

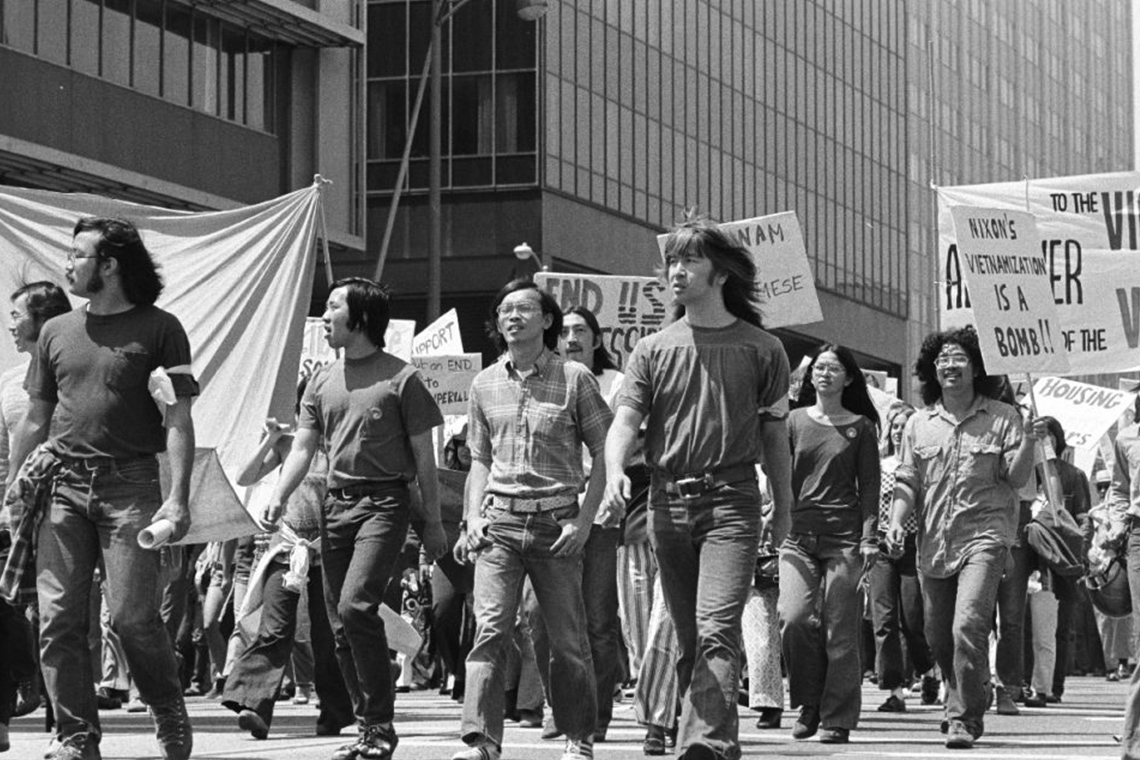

Political activism is not new to Chinese America

In its rabble rousing, this new generation of Chinese Americans is proving true to a tradition of self-advocacy that stretches back to its beginnings in the United States. Indeed, the notion that Chinese Americans have been passive politically has always been a myth and many new immigrants, such as Sean Chen, take inspiration from the struggles of Chinese Americans before them. Since the 1850s, when Chinese first began coming to the United States, they have battled for a piece of the American Dream. In Western mining towns, the Chinese armed themselves with bowie knives and revolvers against other settlers who sought to deny them opportunity.

When the U.S. Congress made Chinese laborers the first ethnic group to be banned from the United States in 1882, the Chinese responded by sneaking into the United States, prompting the first call to “build a wall” on the Mexican border. At courthouses across the country, funds collected by Chinese merchants bankrolled more than 10,000 lawsuits challenging a whole legal architecture designed to oppress the Chinese. Chinese plaintiffs won some of those cases and those victories contributed greatly to the advancement of civil rights for all Americans, undergirding, for example, the push in the 1950s to dismantle the “separate-but-equal” educational system for American blacks.

Politically, throughout the 19th century and in the years after World War II, the Chinese leaned Republican. Labor unions and the Democratic Party had championed legislation blocking Chinese from coming to America, while leading lights of the GOP, such as Fred Bee, one of the founders of the Pony Express, supported the Chinese. During World War II and into the Cold War, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of the Republic of China, cultivated Republican leaders. Chiang blamed the Democratic administration of Harry Truman for not doing enough to fend off the Communist revolution in China in 1949.

The Chinese-American community began to swing toward the Democratic Party in the 1960s as thousands of highly educated Chinese immigrated to the United States from Hong Kong and Taiwan, a trend accelerated by the landmark 1965 Immigration Act, passed by a Democratic Party majority and signed by President Lyndon Baines Johnson, also a Democrat. That law changed the nature of Chinatowns throughout America. In the 1930s, more than 60 percent of the Chinese in America worked as cooks, waiters, domestics, and laundrymen, and fewer than 2 percent had a college degree. By the 1960s, three out of four Chinese had white-collar jobs. In 1966, U.S. News & World Report hailed the Chinese as a “model minority” capable of “winning wealth and respect by dint of its own hard work.”

Chinese Americans started embracing typically liberal causes. One such cause was affirmative action. Activists such as Lily Lee Chen, who left Taiwan to be educated in America in the 1950s, led a campaign to convince Chinese immigrants to avail themselves of government services. “It was difficult in the beginning because so many Chinese Americans didn’t trust governments,” she recalled. But over time, Chen and others like her changed people’s minds. “We were just as needy a group as the Native Americans, Blacks, and Hispanics,” said Chen. “We’re the fourth minority.” Chen became the first Chinese-American mayor in the United States, elected in 1983 as the mayor of Monterey Park in eastern Los Angeles County. Support for affirmative action remained strong throughout the 1990s. In 1996, when voters in California did away with affirmative action in admissions to California’s state colleges, nearly 70 percent of Asian-American voters opposed the measure.

Starting with President Nixon’s trip to China in 1972, Chinese from mainland China began immigrating to the United States. The Tiananmen Square crackdown of 1989 created a massive intellectual windfall for the United States when President George H. W. Bush issued an executive order allowing all the Chinese students in America to stay. Bush’s order gave more than 70,000 highly educated Chinese the right to work in America. Most of them became citizens. Throughout the 1990s, more than three-quarters of mainland Chinese studying in the U.S. opted to remain after graduation. For several years, almost every physics major from Tsinghua University moved to America. Rich Chinese also decamped to the U.S. by the thousands. In 2012, Chinese nationals earned 1,675 of the 10,000 EB-5 visas issued annually by the U.S. government to foreigners who invest $1 million and employ at least 10 people in the United States. Two years later, Chinese obtained 8,308 of those 10,000 slots.

Today, immigrants from mainland China make up close to half of the 5 million Chinese in America, according to Haipei Shue, the Chinese-American organizer. On the streets of Chinatowns old and new, Mandarin Chinese has pushed out Cantonese, Hokkien, and other southern dialects that older immigrant communities spoke. But the change has not only been linguistic. Chinese Americans began turning away from liberal causes such as affirmative action, bolstered by studies such as a 2009 Princeton report in which social scientist Thomas Espenshade suggested that a hypothetical Asian-American student would require an extra 140 points on the SAT to achieve the same probability of admission as a white peer, and an extra 450 points to achieve the same probability of admission as a black peer. Shue estimates that as many as half of first-generation Chinese immigrants now support Republican candidates. Many new Chinese immigrants approved of U.S. President Donald Trump’s tirades against affirmative action and illegal immigration. “There’s a split at the heart of Chinese America,” Shue said.

Liberals lose the hearts and minds of new immigrants

Liberal Asian-American organizations have been taken aback by the rise of the new Chinese-American political voice. During the SCA-5 debate in California, mainstream Asian-American liberal groups accused Chinese-American opponents of the measure of sowing hate and propagating lies. In private conversations, liberal Asian Americans emphasize the crassness of first-generation Chinese Americans, make jokes about their boisterousness and their fondness for shark’s fin soup, and bemoan what they believe to be their casual racism. Many of the more liberal Chinese leaders in America seem to be dismissive of the interests of their country cousins from China.

In 2014, shortly after SCA-5 emerged as an issue in California, Asian-American liberal organizations in New York City backed a proposal to reform or even scrap the entrance qualifications for the city’s elite public high schools, such as Bronx Science and Stuyvesant, to help make up for plunging enrollments among African Americans and Hispanics. Newly elected liberal mayor Bill de Blasio pushed the idea because, he claimed, the current system, which was based solely on the test, reinforced a “rich-get-richer” dynamic. But recent Chinese immigrants viewed the campaign — and the support it won from more traditional Asian-American groups — as a direct threat to their kids. Asian-Americans make up 73 percent of the students at Stuyvesant and 63 percent at Bronx Science.

In New York, Christopher Kwok, a first-generation Chinese immigrant who came to America in 1974 when he was five, was taken by the issue. Kwok had studied Asian-American studies at Cornell University, received a law degree, worked on the U.S. Equal Opportunity Employment Commission, and considered himself firmly in the liberal camp. Still, as he organized meetings in Chinese neighborhoods on the topic, he found himself sympathizing with Chinese immigrant families. A ticket into Stuyvesant or Bronx Science was a pathway to success for these immigrants. How could Chinese-American groups in all good conscience back a change in admissions standards that would end up shutting out Asian-American children? Kwok became more vocal, calling out leading Chinese-American politicians in the city and liberal Chinese-American organizations such as the Asian-American Legal Defense and Education Fund for supporting the change in the tests. “It wasn’t the liberal orthodox position to take,” he said. “The people whom I was like were, ‘Hey, we’re on this side. What’s the matter with you?’” He found himself constantly explaining himself. “I told them I’m trying to protect immigrant kids who have no power and there’s this group of people who are supposed to protect their interests who are not doing their job.”

Margaret Fung, the executive director of the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, said her group supported changing or even doing away with the tests because there was “just too much of a preoccupation with testing as an admission criterion.” She said she tried to keep her focus on the bigger picture and the importance of diversity in schools. In so doing, Kwok argued, such groups began to lose support among the very communities they were formed to serve.

Kwok’s alienation from traditional Asian-American groups continued in 2015 after Peter Liang, a Chinese-American police officer on the NYPD, was indicted on manslaughter charges for killing a black man in the stairwell of a Brooklyn housing project. In solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, many Asian-American organizations, such as Margaret Fung’s group, came out in favor of Liang’s prosecution. Kwok was less sure. He believed Liang, an Asian, was being sacrificed by the American judicial system as a way to placate African Americans enraged by police brutality. Kwok is pictured in a YouTube video of a demonstration against Liang’s indictment as he debates the issue with an African American, telling her, “You should not accept this scapegoat.” Liang was ultimately sentenced to five years of probation and 800 hours of community service after his conviction for manslaughter was downgraded to criminally negligent homicide.

China’s rise and the appeal of Donald Trump

For their part, newer immigrants from China — with their advanced degrees and financial resources — sneer at what many of them call “Chinatown Chinese.” They view attempts by liberal Chinese organizations to support affirmative action and other progressive causes as little more than currying favor with white liberals. “I feel like these organizations took these stances so they could get a seat at the table. They are being progressive simply to be progressive, not to solve anything,” said Linlin Chen, a first-generation immigrant who blogs frequently on the issue. “They have become divorced from the community because the community is changing.”

But other things are changing, too, particularly China, which is often an overlooked factor in this story.

China’s rise has shaken the balance of power within Chinese America. New immigrants are not ashamed of their homeland. Instead, China’s emergence as a global power has emboldened many new Chinese immigrants to become more politically active in the United States. What’s more, the resentful nationalism that is promoted by the Chinese government and that accuses the United States of trying to contain China has been internalized by many new immigrants who now allege that the American system of affirmative action is there to try to contain them and their children.

In addition, few of the newer immigrants seem to have much sympathy for the idea of diversity. A popular Chinese blogger on WeChat who goes by the name Xiexie5668 remarked that while affirmative action made sense “in the last century” to right historic discrimination against minorities, its use in today’s America as a way “to dole out racial quotas” marked a distortion of its original purpose. “Different races do indeed go after different opportunities and have different outcomes,” he observed in an interview conducted over WeChat. “But the key factor is no longer racial discrimination.” It was culture, he suggested. “Different races have differing views on the importance of a family and how a family should view education,” he said. “Addressing these problems can’t be done through affirmative action.”

Steven Chen, a Chinese immigrant who moved to America from China 30 years ago and has been active in his community, observed that among many first-generation Chinese Americans, the sense of superiority to other groups is powerful. “They seem not to like Hispanics, African Americans, and even Jewish people,” he said. “They seem also look down upon the old Chinatown Chinese and Chinese from Taiwan. At the same time, they also believe that they are heavily discriminated against by other groups. It is ironic.”

“Some of them say, ‘We came here not because the U.S. has colored people but because the U.S. has white people,” he said. “We have joked with them and said, ‘Hey, you’re not yellow. You’re off-white.’”

To Chen, that attitude explains why many first-generation Chinese Americans supported Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. “China has been rising faster than America for the last 20 years, so it’s natural that many of us feel that something is fundamentally wrong with the U.S.,” Chen said. “When Trump said America is all screwed up, it resonated with many of us.”

Can new immigrants be brought “into the tent”?

A sense that Chinese America was also becoming “all screwed up” is what prompted Frank Wu, the new chairman of the Committee of 100, a group of prominent Chinese Americans, to write an open letter for the Huffington Post on March 18. Wu, a law school professor and the author of the critically acclaimed Yellow: Race in America Beyond Black and White, had watched with dismay as all sides of the Chinese divide descended into progressively fractious bickering.

Addressing liberals such as himself, Wu lambasted them for looking down on the new arrivals. “We do not represent them. We are not sympathetic to them. We have betrayed them. We cannot even communicate in the language they deem ours,” Wu wrote. The failure of progressive Chinese-American groups to reach out to the new generation, Wu warned, could doom Asian-American efforts with other minority groups. “It could signal the end of the project altogether,” Wu wrote.

Wu was surprised at what happened next. While there was some pushback among his comrades on the left, the more powerful reaction came from the new arrivals. Wu was blasted on WeChat and wenxuecity.com by scores of angry Chinese who accused him of being condescending and ignorant. A Chinese translation of Wu’s open letter distorted his original tone of paternal solicitude toward the new arrivals into one of haughty superiority. It did not play well. Wu issued a second open letter that apologized for the first. “I was ineffective,” Wu said in an interview. “I was an idiot and did not communicate my message well.”

Other leading lights among the Chinese-American community have sought to bridge the gap or even profit politically from the energy generated by the newly arrived Chinese. S.B. Woo was once one of the highest-elected Chinese Americans in the United States: the lieutenant governor of Delaware. Woo started the 80-20 Political Action Committee in the 1990s as a way to mobilize Asian Americans to vote for the presidential candidate who best represented their interests. Now Woo, at 79, finds himself jetting from coast to coast trying to bring the new Chinese immigrants into his tent. Like other Chinese Americans, Woo admires the energy of the new arrivals, but he worries about their use of personal attacks reminiscent, he said, of a “struggle session” conducted by Red Guards in China during the Cultural Revolution. Woo fears that if the gap within Chinese America is not bridged soon, the community could be split for years.

Others are more sanguine. Many note that the children of first-generation Chinese Americans tend to be more liberal than their parents and appreciate the benefits of diversity and affirmative action. In March 2016, one younger Chinese women published a passionate if not slightly overwrought letter to her father, accusing him of racism against black people because he supported police officer Peter Liang. Other Chinese young people interviewed for this story said that they valued diversity and that they took what they assume to be tougher admissions criterion for Asian-American kids in stride.

“Sometimes my mom will harp on [affirmative action] a bit,” noted Kevin Sun, the son of blogger Linlin Chen. “But I understand it and accept it. I’ve grown up with it.” That said, Kevin observed, his mother’s activism had inspired him. “My mom wanted me to be aware that I’d have a harder time and that I have to work for everything,” said Sun, who will be entering Northeastern University in 2018 after a gap year in China. “She definitely gave me a sense of confidence that I can do almost anything I put my mind to.”