U.S. poet laureate Tracy K. Smith on Chinese poetry, language, and the allure of China

"Because I have this other language, I have a different emphasis, a different cadence that I now have permission to live and think in — and that carries over into the person I am in English as well.”

Tracy K. Smith, who began her post as the 22nd poet laureate of the United States in September, has expressed a desire to promote poetry in underserved backwaters and remote corners, to take it outside of leafy campuses such as her own at Princeton, where she is director of the creative writing program. As she said in an interview in June, “I see the poet as someone who has made a commitment not just to self-expression, but to an active and an eager listening to the world and the voices outside of the self.”

Perhaps that explains why we’re in the back of a van in Beijing on a Thursday morning, shuttling from a hotel to a university for a public reading. It was merely a coincidence that China, of all places, would be Smith’s first major destination since officially becoming America’s most visible poet, but it was also somewhat fitting — if one’s committed to taking poetry on the road, why not all the way to the other side of the world?

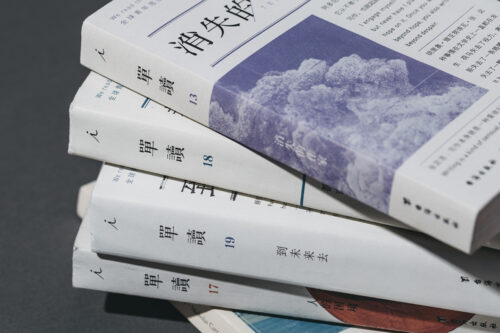

In fact, last week marked Smith’s second time in Beijing, following a trip in April. On both occasions, her main purpose was to visit a poet she’s co-translating, Yi Lei (伊蕾), who was very influential in the 1980s and 1990s but remains obscure outside of Asia (a fact that might soon change, with the pending publication of a Smith-translated book). Smith was introduced to Yi’s work in 2013, starting with her most famous poem, “A Single Woman’s Bedroom” (独身女人的卧室). “I just felt so much connection to her,” Smith says. “It’s a long poem written in many brief sections, which is something that I tend to do with my work; it’s a poem that’s thinking about female identity and sexuality and subjectivity; and it’s also moving toward these large-scale thoughts about philosophy and about humanity, and I was just so drawn in by her voice.”

Despite only reading the poem via translator Changtai Bi’s rigid initial draft, Smith was infected by Yi’s “urgent energy.” “I could tell there was a lot happening in this poem that I was drawn to,” she says. She eventually translated all of it.

We sat down with Smith — in the back of that van, remember — to talk about the nature of language and poetry, and what she likes about Beijing.

Anthony Tao: The New York Times said you planned to use your time as poet laureate to go into small towns and rural areas as a “literary evangelist,” to spread the gospel of poetry, as it were. How do you feel about that phrase?

Tracy K. Smith: I sort of set myself up for that phrase because I was talking about poetry as good news, thinking about how, despite all of the discouraging input we get from the media, poetry allows us to process that information, to reflect upon our lives, and to talk to each other in ways that are necessary and humanizing. I guess I don’t mind that moniker. What I’m more interested in is the possibility of going into these small communities and listening and sharing and thinking about what poetry means in different places, and I think that will be instructive to all of us.

AT: Beijing is obviously neither a small nor a rural place…how’s your Chinese?

TKS: Xiexie [谢谢, thank you], that’s what I’ve been able to say. At my age, I feel, “How would I ever?” But I have such a desire to come back to make this more of a regular place in my life, so maybe I can learn.

AT: And what is your relationship with Chinese poetry?

TKS: I know a little bit about the history, but it’s very patchy. I’ve read some poems of [ancient poets] Li Po (李白) and Du Fu (杜甫), and then leap forward to [the 1970s/1980s “Misty Poet”] Bei Dao (北岛)…and now, some of the more recent translations [of Chinese poets] that have come out in the States. So it’s a really incomplete body of knowledge so far. But it’s still growing, a growing region of my consciousness.

“Poetry is the one occasion in language where what doesn’t fit into language is somehow given expression.”

AT: I find there’s truth in the idea that language sets the foundation of how one thinks — what do you think about that? And Chinese and English being so different, how do you find similarities in those two worlds of poetry?

TKS: I agree that language sets the parameters of our conscious thoughts, and so the principles and properties of the language we were born into determines a lot of what we’re able to think. I remember when I learned Spanish, realizing, “Oh, there’s a whole other version of myself that I now have access to.” Because I have this other language, I have a different emphasis, a different cadence that I now have permission to live and think in — and that carries over into the person I am in English as well.

But what I really think about poetry is that it is the one occasion in language where what doesn’t fit into language is somehow given expression. It’s sort of a conundrum because we’re using this tool that’s finite, but we’re using it in very different ways — musical ways, associative ways, ways that create a visceral sensation, ways that don’t rely on linear sense. What that results in is something that’s bigger than the vocabulary that it’s built of, and that’s where I think poets are able to connect to each other beyond culture.

I hear that urge and that impulse in the poems [of Yi Lei] I’m translating now, and it’s almost…I don’t know how to say it. I think the silences in poems do a lot, the spaces where there is no writing does a lot. Or maybe it’s just where we get to allow these other things to echo and expand, or to grow a little bit before they’re countered or followed up by something else.

But I also feel like there’s so much in Yi Lei’s poetry that’s really thinking about freedom, thinking about the ability to be a genuine original self despite all of the obstacles that exist in society and in our sense of doubt, or the ways that propriety seeks to rein us in. So those are the places where the poems are pushing against boundaries of language, that’s where a rash statement or image comes in to help bring the poems to a place where they cross the line beyond what a statement is able to transmit.

“Poetry allows us to reflect upon our lives and to talk to each other in ways that are necessary and humanizing.”

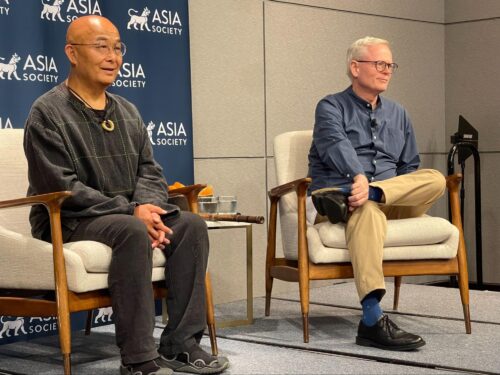

AT: You recently took part in a translation workshop as part of your trip [organized by Ming Di (明迪), along with renowned poets such as John Yau, Kevin Young, Mario Bojórquez, Xi Chuan (西川), Ouyang Jianghe (欧阳江河), etc.]. What was it like to see your poems in Chinese?

TKS: I wish I could speak the language so I could really hear what it became in this other language, which I can’t. I love the sound. I’m mystified, I’m fascinated by the characters. Even though I know what the poem said, I don’t know what they say. But I think it’s exciting to know that there’s a version of my poems now that can be touched on for readers in a different language, and I’m curious to know how the references live on the other side. I know there’s a lot of choices. Ming Di translated a poem [of mine] called “Ash,” and she said, “Okay, is it this kind of ash, is it this kind of ash?”

So just thinking about the possibilities. And then having to make that affirm certain meanings or implications also makes me have to listen to my poems differently. And some of the things that happened unconsciously, I’m urged to reflect upon them more consciously now because I have to say, “Is it that or that? Well, actually, it’s more this thing than the other, and this is why.”

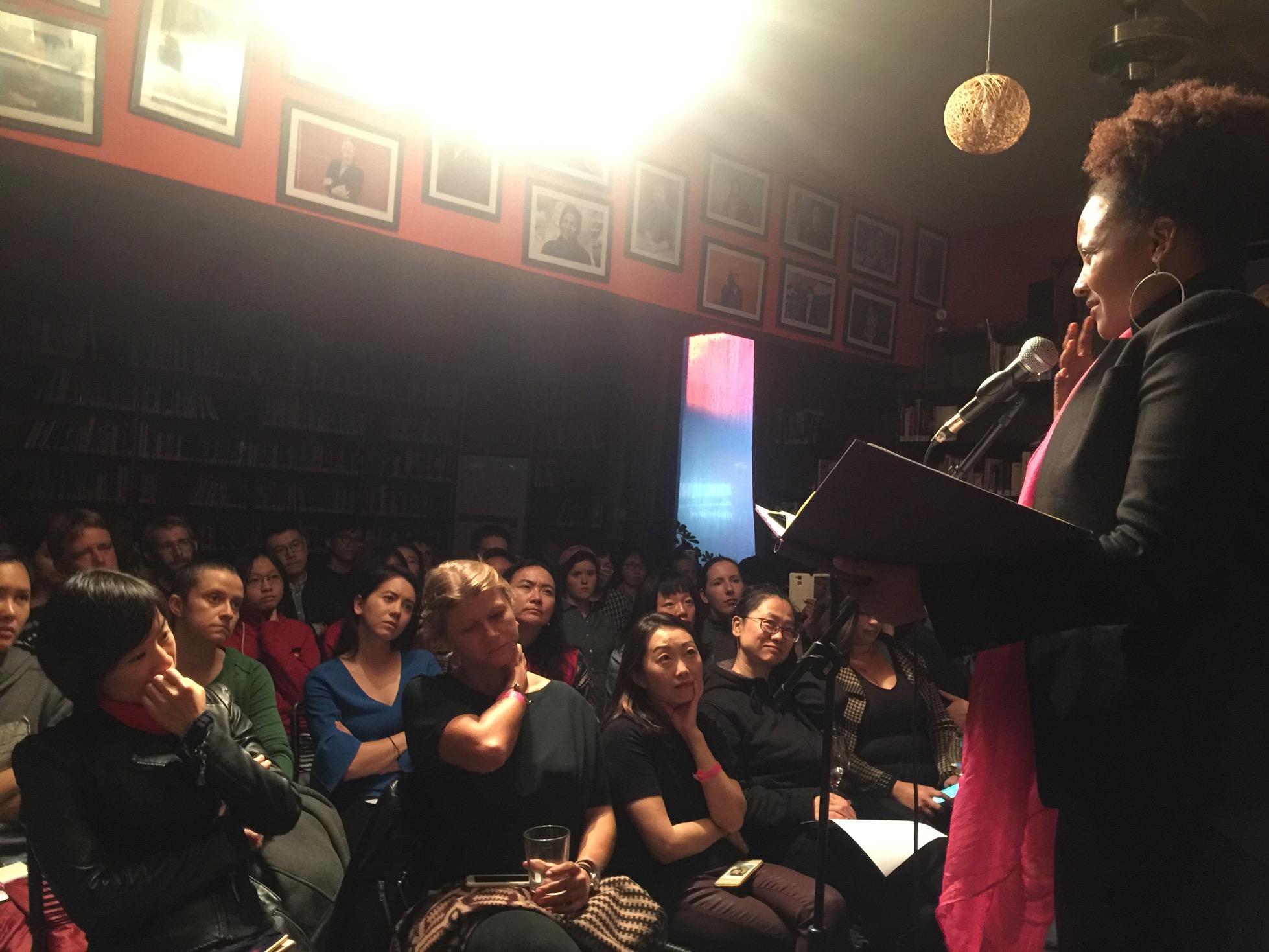

AT: On Monday, you read poems [at The Bookworm] about the Lama Temple [a Beijing landmark] and Nanluoguxiang [a popular alley flanked with cafes, bars, and shops]. How do you decide if a place is worth writing about, and if you could write about anything else in China, what would it be?

TKS: I think a place tells me if it’s worth writing about, because it speaks to me on some level. If I were to…when I write more poems about China, they’ll probably have to do with the people whom I’ve met and some of the interactions, some of the spaces between languages, and then some of the ways that space gets filled up. It’s been so beautiful.

Tracy K. Smith is the author of a memoir and three books of poetry, including the Pulitzer Prize-winning Life on Mars. Her fourth collection, Wade in the Water, will appear next April.

The Bookworm event in full: