Guggenheim’s controversial China exhibition revels at the intersection of art and politics

Ami Li walks us through the Guggenheim's current exhibition, Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World, which highlights the major artists and movements in the Chinese art scene from 1989 to 2008.

Between 1989 and 2008, China saw miraculous economic growth, significant political change, and heavy-handed reactions against free speech and artistic expression. Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World — the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s exhaustive survey of Chinese contemporary art spanning this time period — thematically and chronologically highlights the major movements, individuals, and collectives active in the art scene within China and abroad from before the Tiananmen demonstrations and crackdown to the Beijing Olympics. Organized by the Guggenheim’s Alexandra Munroe with guest co-curators Philip Tinari and Hou Hanru 侯瀚如, the show features a who’s who of the Chinese art world, and cogently presents a breathtakingly diverse slate of artistic reactions to the rapidly changing country.

Prior to the exhibition opening earlier this month, news broke about three pieces that would not be shown — Huang Yong Ping’s 黄永砯 Theater of the World, which gave the exhibition its subtitle, Sun Yuan 孙原 and Peng Yu’s 彭禹 Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other, and Xu Bing’s 徐冰 A Case Study of Transference — due to the incorporation of live animals in the works. Much digital ink has been spilled on the controversy, whether regarding the muzzling of artistic expression and complicity in censorship or the treatment of animals. The museum supplies a brief, general explanation for the absence of the three works, pinning the decision for removal on general concerns for the safety of all.

And so, bare cages greet visitors as they begin their ascent into the exhibition. Theater of the World was meant to house a menagerie of insects and reptiles living inside an environment of controlled chaos that viewers would have been able to observe unmolested from the outside. Now the empty vessels bear more than a passing resemblance to a concurrent exhibition, Good Fences Make Good Neighbors, Ai Weiwei’s 艾未未 public project comprising more than 300 pieces installed throughout New York City — which, incidentally, is also drawing controversy. Instead of gilded cages impeding the flow of humanity around the world, these barriers are standing in the way of ideas and artistic exchange.

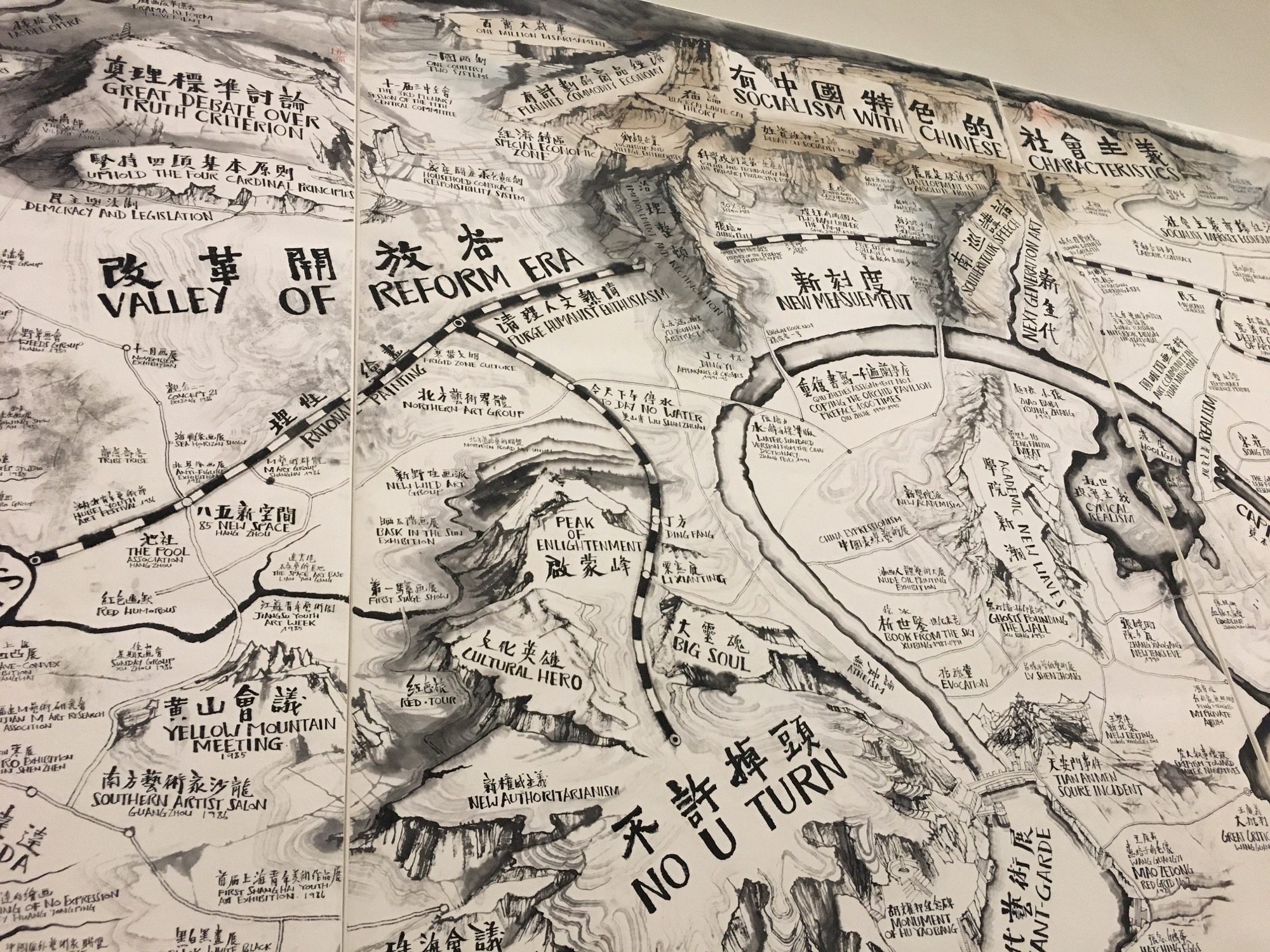

Next to Theater of the World is an equally monumental achievement, Qiu Zhijie’s 邱志杰 Map of “Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World.” The work is a conceptual map and tongue-in-cheek timeline that spans the historical period of the show. The result is an exquisite, humorous summary of the exhibition, with plenty of Easter eggs for China art and history buffs. The piece, which includes historical events, artistic movements, technological advances, and miscellaneous phenomena, shouts out everything from ’85 New Wave to the Belt and Road Initiative.

On the flipside, one could argue — and this could be applied to the whole show — that Qiu’s work is too opaque for non-China observers to understand or appreciate. Like most good art, the pieces in the show are dense with meaning. They incorporate references to everything from mythology to religion to recent and ancient history. And while the wall text and audio guide (narrated by Tinari) both do an admirable job of filling in the gaps, a certain layer of lived understanding just isn’t there to enable the average viewer to, for instance, chuckle at the deep-fried toy tanks in Zheng Guogu’s 郑国谷 Visual Art, Add Oil! March Forward!, or to react to the question I overheard regarding Wang Xingwei’s 王兴伟 New Beijing: Were the supine penguins that were depicted a commentary on Tencent’s QQ messaging service?

(They aren’t, for the record. The penguins are stand-ins for the injured students being carried away after being gunned down on June 4, 1989.)

Lived experience also affects one’s understanding of the exhibition’s most eye-catching work, Chen Zhen’s 陈箴 monumental sculpture Precipitous Parturition, a 20-meter-long dragon installed in the middle of the museum’s soaring rotunda. Constructed of bicycle tires, tubes, and frames, the belly of the beast is filled with tiny plastic toy cars. At the time of its fabrication in 1999, Chen had just returned to his native Shanghai after living in Paris for over a decade; he saw an advertisement promoting the arrival of personal cars to his hometown. The historical context is crystal clear: At the time, there was a colossal confrontation between bikes and cars, Communism and capitalism, old and new. In 2017, the sculpture of a dragon swallowing automobiles is as much about China’s ascendant role fighting climate change and the flood of bike-sharing companies as it is about two wheels versus four.

As the exhibition winds its way up the museum, the works appear in roughly chronological order, with each time period tied to various thematic contexts. Immediately after 1989, artists retreated into oblique conceptualism, distilling artistic practice into impenetrable symbols, numbers, forms, and rules, exposing the absurdity and complicity of familiar systems. On display here are many examples of exercises, ephemera, and art-world jokes committed by the New Measurement Group, including Geng Jianyi’s 耿建翌 Forms and Certificates: 28 intake forms sent to potential participants in the 1988 Huangshan conference on modern Chinese art. The forms start out anodyne, but the requests gradually become more and more absurd, asking participants to list their favorite plant, family, and medical history. Some — but not all — of the recipients were in on the joke, and responded in kind. Ultimately, the completed forms were exhibited in the watershed China/Avant-Garde show at the National Museum of China in 1989.

The second-to-last section, subtitled “Whose Utopia,” covers the period of rapid change (which one isn’t?) between 2001 and 2008, when Beijing was making preparations to host the Summer Olympics. The pieces in this section highlight the optimism, ambition, confidence, and hope that colored the time, feelings shattered by the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, riots in Tibet, and first signs of control on what was then a new free speech sandbox called the internet.

Nowhere is this pivot toward authoritarianism more starkly represented than in two grand-scale Ai Weiwei works executed in 2007 and 2009. Fairytale brought 1,001 Chinese tourists to Kassel, Germany, the site of Documenta 12. Ai recruited participants on the internet, designed luggage for them to bring to Germany, housed them in dormitories designed by his studio, and filmed their experiences. The project allowed ordinary people access to the insular contemporary art world, promoted cross-cultural exchange, and even foreshadowed the power of the Chinese tourist in outbound travel. Fairytale refers to the literary history of the Kassel region, the miraculous nature — the granting of a wish — of traveling there, and the impossibility of it happening again.

Following the devastating Wenchuan (Sichuan) earthquake the next year, Ai once again harnessed the power of the internet, crowd-sourcing information from netizens to expose the greed and corruption — manifested in the city’s shoddy infrastructure — that resulted in the deaths of thousands of children. As Ai exposed the darker side of China’s rise, the government tried to muzzle him, shutting down his social media platforms and sending goons to physically intimidate and assault him. 5.12 Citizens’ Investigation, compiled through the harassment, is an austere printed table of names — 5,386 in all — of the children who died. Juxtaposed with Fairytale, it is a stark reminder of how fast cultural environments become inhospitable to art when power and pride are at stake.

Inside the Guggenheim’s Tower 7 gallery are the exhibition’s three final works, each bathed in violence and suffused with menace. A blank TV screen shows the title card for what would be the video of Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other. If not for protests resulting in the work’s removal, it’s here that we’d see agitated pit bulls strapped to treadmills, noses barely touching and bodies straining at their restraints, hungry for blood.

Visitors then encounter Yang Jiechang’s 杨诘苍 monumental, Motherwellian Lifelines I, painted for the 10th anniversary of the Tiananmen incident. Gashes of black ink sweep across the paper, modeled after a diagram of the June 4 clashes by critic and curator Li Xianting 栗宪庭. Installed around the upper walls is 2009-05-02, part of Gu Dexin’s 顾德新 swan song from the art world. Thirty-five panels of red characters repeat the same text:

We have killed people we have killed men we have killed women we have killed old people we have killed children we have eaten people we have eaten hearts we have eaten human brains we have beaten people we have beaten people blind we have beaten open people’s faces

The survey ends in 2008. Of course, much has happened in China, and in the art world, since then. Scenarios once deemed unimaginable are reality. By leaving viewers with a sense of warning, promising violence yet to come, the show reminds us that the journey is far from over, and the world soldiers on.

Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World is at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum through January 7, 2018.

Also by Ami Li:

10 can’t-miss artworks at the Guggenheim’s ‘Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World’