Suing the homophobia out of China’s textbooks

Although China officially removed homosexuality from its list of psychiatric disorders in 2001, homophobia remains a big problem throughout the country, which many Chinese LGBTQ rights advocates continue to combat. Sometimes, they take unexpected tacks. In Guangzhou, a university student going by the pseudonym Xixi 西西 is suing Jinan University Press (JUP) and online retailer JD.com for publishing and distributing a psychology textbook that describes being gay as, among other things, “abnormal,” “deranged,” and a “disorder.”

According to a number of people interviewed for this story, including lawyers and activists, this is the first time someone has sued a publisher over such content.

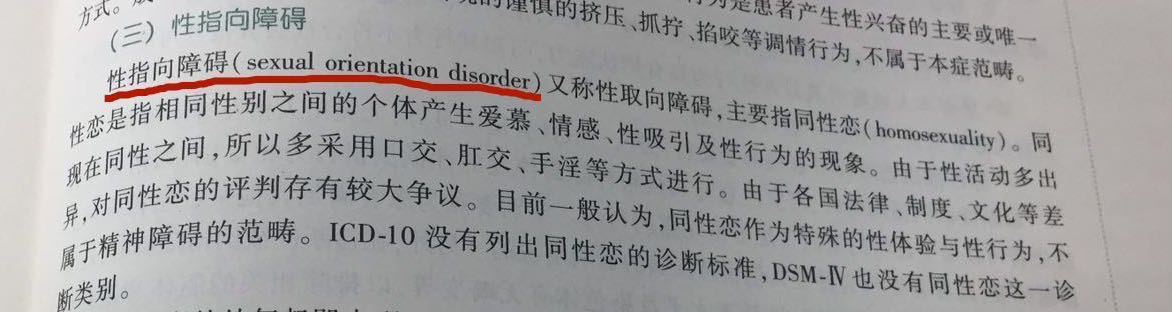

A third-year sociology major at South China Agricultural University 华南农业大学, Xixi first became aware of this issue when a friend alerted her to offensive passages in the textbook Psychological Health Education for University Students (大学生心理健康教育 dàxuéshēng xīnlǐ jiànkāng jiàoyù), published by JUP. “That’s when I realized the negative impact these teaching materials can have on gay students,” Xixi says.

Xixi met with JUP representatives to try to get them to edit the textbooks, to no avail. “I basically just explained to them that China had already stopped considering homosexuality an illness, so describing it as a disorder or an impediment was simply incorrect,” she says. JUP denied responsibility for the content and told Xixi to take the issue up with the editor.

Xixi says JUP’s deputy editor-in-chief, Yan Liqing 晏礼庆, told her that while he wasn’t an expert in the field, Chinese society simply wasn’t as accepting of homosexuality as other countries.

In June 2016, Xixi also spoke to JUP editor Zeng Qing 曾庆, once on the phone and once in person, who told her that changing the textbook would take time, but that she would look into handling it as soon as possible. When Xixi tried to follow up two weeks later, she discovered that her phone number had been blocked. “These reactions were extremely frustrating, but also left me very angry,” Xixi says.

It was then that she decided to sue.

Interestingly, the lawsuit is not based on discrimination law, as might be expected, but on consumer rights. Xixi alleges that Psychological Health Education for University Students does not meet quality requirements set out by Chinese law and thus violates her rights as a customer. The relevant Chinese legal guideline is relatively straightforward: Incorrect content cannot make up more than 0.1 percent of a given book. Should it do so, both the publisher and book retailer bear responsibility for these mistakes — which explains why Xixi’s suit names both JUP and JD.

An earlier, similar lawsuit

Xixi is not the first student who has attempted to rectify homophobic content in college textbooks through China’s courts. A previous attempt failed in March 2017 when another Guangzhou student, going by the pseudonym Qiu Bai 秋白, sued the Chinese Ministry of Education (as documented on her WeChat; note that the difference is she didn’t sue the publisher).

Having grown up in the southern Chinese countryside, Qiu sought to better understand her own sexuality at Sun Yat-sen University 中山大学, but was shocked to come across books describing what she was feeling as an illness. Connecting with local NGOs and other LGBTQ students helped her come to terms with her own sexuality.

“A while later, I was talking to a medical student, who was also lesbian, but wouldn’t believe me that that was perfectly fine,” Qiu remembers. “She was studying medicine and used her own textbooks as evidence that being gay was an illness!” After this experience, Qiu contacted publishers and local authorities in Guangdong to get the textbooks changed, then finally decided to sue the Ministry of Education.

Qiu took issue with textbooks describing homosexuality as a “sexual orientation disorder” (性取向障碍 xìng qǔxiàng zhàng’ài). She argued that the ministry had failed to ensure the quality of textbooks used in Chinese universities, which it was ultimately responsible for. In March 2017, the Beijing Supreme People’s Court decided against her, leaving no room for further appeals. “I was extremely disappointed when the result came in,” Qiu remembers. “But this simply means I will need to continue the fight, talking to publishers one by one.”

While reporting the progress of her lawsuit online, Qiu received many messages of support — one of them was from Xixi, who says she was inspired by Qiu when she eventually pursued her own lawsuit.

According to Yu Liying 于丽颖, a lawyer who represented Qiu Bai and now represents Xixi, the main difference between the two suits is that Xixi is going the route of a civil rather than an administrative lawsuit. At the time of Qiu’s lawsuit, her own lawyer, Wang Zhenyu 王振宇, pointed out that the government usually wins lawsuits it is involved in. Suing a private actor rather than a government agency might play to Xixi’s advantage.

In 2014, activist Yang Teng 杨腾 famously won a civil suit against a conversion clinic in Chongqing, which advertised being able to “heal” homosexuality using electric shock therapy, a method it described as both safe and effective. Similar to Xixi’s suit, Yang’s case was based on consumer rights and alleged fraud. It also implicated Chinese search giant Baidu, which had displayed advertisements for the conversion clinic. The final court judgement ruled against the conversion clinic — ordering it to pay Yang $560 — but found no fault with the search engine.

Obstacles and delays

For now, it is unclear when Xixi’s case will actually be litigated. An initial court date was set for late October 2017 before being canceled on short notice. A second court date on January 19 was likewise canceled.

Darius Longarino, a research scholar at Yale Law School, considers the repeated delays a bad sign: “The court has delayed twice, saying it needs more time to examine evidence. This may be, but the court is also likely under internal political pressure and hasn’t yet determined how to handle the case.” Xixi’s lawyers are more optimistic, but caution that they are not allowed to make predictions about a case they are litigating. They also point out that legal proceedings in China need to be completed within six months from the day a case is registered; however, the court can extend this period to one year at its discretion.

According to court documents provided by the plaintiff’s lawyers, the case is registered in Suyu District People’s Court in Suqian City, Jiangsu Province. A representative of the court said he could not comment since the hearings had not started yet. He was also unable to provide any information as to when a new date for the case would be set.

When called for comment, representatives of Jinan University Press said they were not sufficiently informed to comment.

While Xixi waits, Qiu Bai, who lost her suit last year, continues her fight against homophobic textbooks outside the courts. After finding discriminatory and often false statements about sexual minorities in 47 textbooks across China, she began contacting responsible editors and publishing houses. Qiu says 20 publishers acknowledged that the content constituted a mistake and promised to change it. In the case of a legal textbook, Marriage and Inheritance Law (Chinese University of Political Science and Law University Press), a new version had already been published in August 2017. The previous version of this textbook stated that “same-sex marriage goes against natural law,” that “homosexuality causes moral bankruptcy in society,” and that “sex between same-sex partners is illegal.” The 2017 edition omitted some of these statements, changed others — for example, turning “marriage is necessarily between a man and a woman” to “marriage is usually between a man and a woman” — and provided additional legal context by adding a list of countries that have legalized same-sex marriage.

Given the misinformation in a wide range of Chinese textbooks across a number of disciplines, one might expect more court cases on this issue. However, speaking from her own experience, Qiu Bai cautioned that students in particular might be worried about stirring conflict with their universities, which might threaten their graduation status out of fear for negative headlines. She herself had been asked repeatedly by her alma mater to drop her suit.

So far, Xixi has not encountered such resistance from her university. “My supervisor disapproves, but has not interfered in any way,” she says.

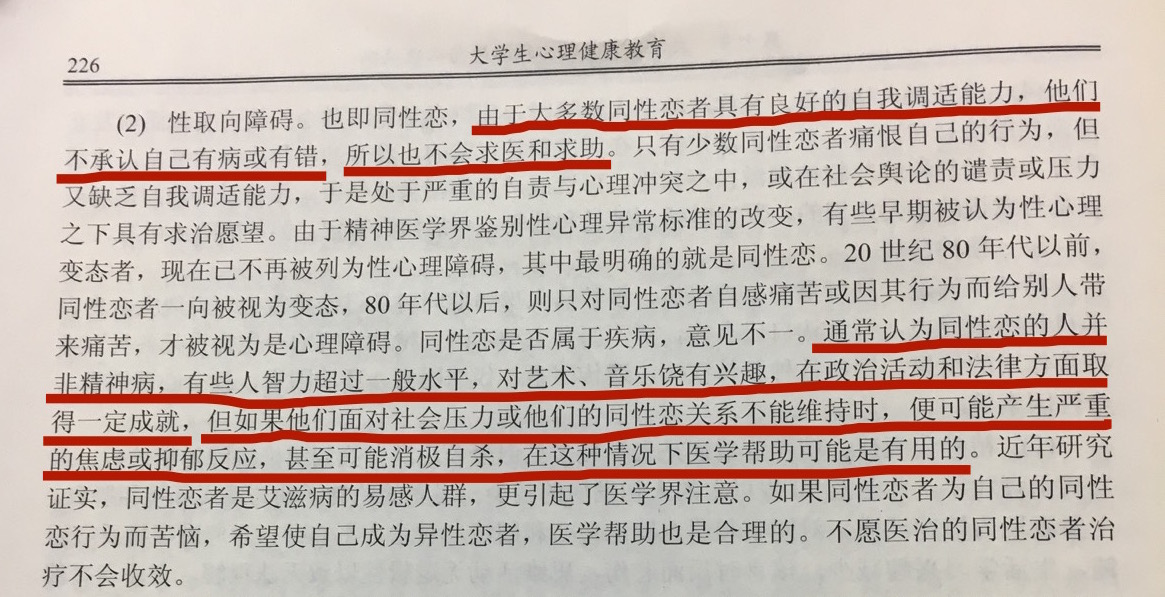

Excerpt from Psychological Health Education for University Students:

As the majority of homosexuals possess a good ability to self-adapt, they don’t admit they have an illness or are wrong, so they also won’t consult a doctor or seek help…. Gay people are not generally thought of as having mental illness, some have intellects that surpass what’s normal, with a deep interest in art and music; they excel at political activities and aspects of law. But when they are unable to face societal pressures or their homosexuality, then it’s possible that serious feelings of anxiety or depression will arise, to the point that they’ll attempt suicide. In these situations, medical help might be of use.