Black Lives China comments on ‘Africa’ sketch in CCTV gala

By Hannah Getachew and Runako Celina Bernard-Stevenson

This piece was originally published on the website Black Lives China, whose mission is “to capture the full breadth of the black experience in, around, and in relation to China,” under the headline “Racism – with Chinese characteristics: How Blackface darkened the tone of China’s Spring Festival celebrations.” It is republished here with permission.

The events of the now infamous 2018 Chinese Spring Festival/New Year gala is being hotly debated online amongst Africans in China and elsewhere in the world. Chinese people, and now even the Western press, have chimed in. Some 800 million people are likely to have tuned in to the show to witness, amongst other things, a Chinese actress parade around stage in blackface, complete with prosthetic butt and chest. As many will by now be aware, the tale being told in the skit in question goes something like this:

An African girl is under apparent pressure from her mother (played by Chinese actress Lou Naiming 娄乃鸣 in blackface) to marry at the age of 18. She doesn’t want to get married but instead wants to move to China to study because, as she passionately reminds us, China is amazing. So she gets her Chinese friend to pretend to be her fiancé in an attempt to trick her mother into believing that she is indeed following her wishes. The mother is thrilled to hear that her daughter plans to marry a Chinese man and tells the audience how grateful she is for how much China has done and is doing for Africa. Yet before long, the secret is revealed when her fake fiancé’s real bride-to-be (a Chinese woman) appears on stage in a wedding dress, ready to say “I do”!

When her daughter explains why she lied about getting married and insists on moving to China, the mother seemingly forgets her desire to see her daughter married off. Instead, she passionately stares into the audience and states “I love Chinese people. I love China.”

There seems to be some confusion about whether or not the accompanying monkey character was played by an African man.

The play ends as it began — playing Africa’s finest export, Shakira, while “the Africans” dance on stage. [Editor’s note: Shakira is not from any African country.]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GAhaj5sG8fc

Diverse Africans, Diverse Opinions

The play made reference to 非洲 (Fēizhōu) several times, once again treating the African continent as if it were a singular entity. In fact, there are 55 countries across the African continent and its landmass is three times that of China. This skit misrepresents sub-Saharan countries and the global black diaspora, yet doesn’t make any reference to North African countries. Simply put, Africa is too large, complex and diverse for any singular narrative.

This principle applies to the content of this article as well. Black Lives China does not presume to encompass the full diversity of the black experience in response to this skit, and readers should be wary of any article which claims to do so.

Amongst the black community, there are members who find this skit harmless, entertaining or largely irrelevant. For them, elements of the play ring true. Zebras, lions, and monkeys are native to sub-Saharan African, they will say. Some were amused by the music and dance, tapping their feet to the rhythm of the drums on stage.

Others call the play a distraction. Any racially insensitive portrayal of black Africans can only exist due to the economic power-dynamics between Africa and China, they say. Following this line of argument, one can point out the monetary imbalance in the level of financial investments China makes in African countries, versus the other way around. Once African countries organize and negotiate investments with China based on clear regional and continental priorities, racism in China will gradually fade away. These are just a sampling of the many views in the black community on the skit.

Racist or not? Our take

The question on most commentators’ lips seems to be whether or not the skit, and in particular the depiction of the mother, was racist or racially insensitive.

For many, the physical stereotypes paraded during the skit recreate historic racism and follow upon earlier crimes such as the dehumanization of the enslaved South African woman Saartjie “Sarah” Baartman, who was caged in European circuses for the exhibition of her naturally curvaceous body.

The blackface brings to mind minstrel shows of the 19th century and the purposeful mockery of black people, plus the exaggeration of their characteristics for the entertainment of others. It dealt in the dehumanization of people of African descent — free Africans and the enslaved — on stage to demonstrate the believed inferiority of the African on every possible level. This depiction, when juxtaposed against the European, was intended to show [the European’s] innate superiority. This type of portrayal can even be seen as recently as 30 years ago in American shows such as the 1978 Black and White Minstrel Show.

Monkey See, Monkey Do – Did China simply copy American racism?

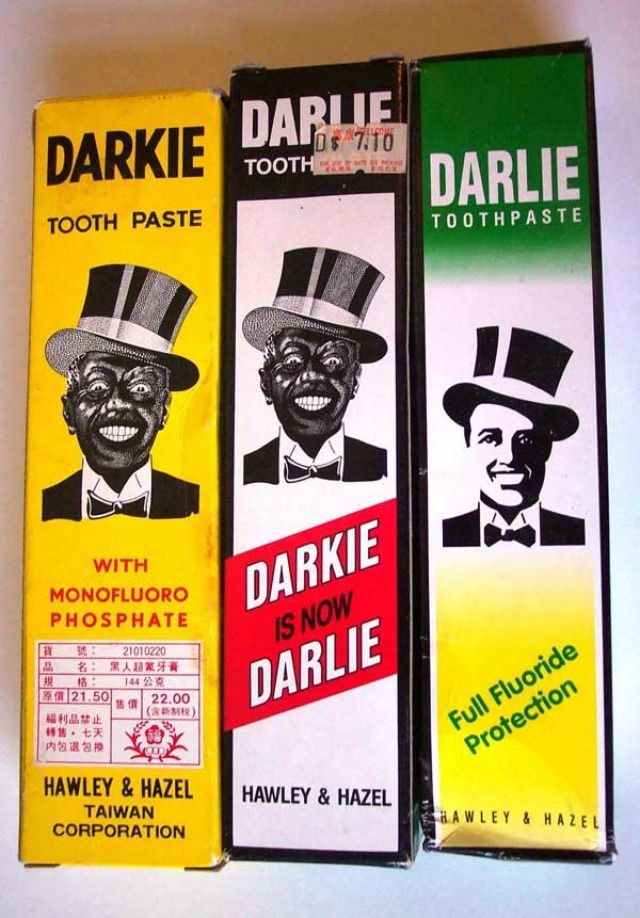

In detailing this history, one should also remember that racism clearly is not a Chinese invention. While it would be a huge simplification to state that China simply learned racism from the West, there are definitely some manifestations of racism (or racially insensitive behaviors) that clearly speak to a history in which China has no or little part in. Sometimes American firms have been guilty of bringing their racism to China’s shores, as is the case with the popular toothpaste 黑人牙膏 (hēirén yágāo), or “Darlie,” previously known as Darkie. The brand is a household name in China, and while its part-owner — American company Colgate-Palmolive — has tried to distance its brand from the controversial “Black people’s toothpaste,” the minstrel show logo with its origins in blackface are unmistakably American imports. This is just one example of the ways in which the West can be culpable for racist attitudes in China.

But does all this culminate to suggest that China shouldn’t be held accountable for their dalliances with racism?

Some have stated that China and Chinese people have little knowledge of the historical context of blackface and even less understanding of racism. Therefore, it is argued that the Chinese New Year gala skit isn’t racist, as there was no racist intention behind it. While this article will deal with the matter of what may have been the message behind — and intention — of the skit later, it is important to note that racism does not rely on one’s intentions but instead on the impact of the action on the target person, or in this case, group. That is what takes precedence and must be considered first in each instance. Additionally, ignorance should never justify racism or mitigate the ultimate impact of said actions. As such, ignorance cannot be a defense to the recreation of racial stereotypes.

The claim that China has a complete lack of awareness around racism is extremely prevalent…Yet several things make this difficult to comprehend. Despite China not having a long history of “yellowface,” they still are hugely sensitive to depictions of Chinese people that they deem inappropriate and offensive. In fact, there seems to have been severe reactions in China and its diaspora against racism towards Chinese people.

How does China react when it receives similar treatment?

While China may not have any historical reason to understand the offensive nature of blackface, the idea of mimicking the physical or facial features of Chinese people has caused great upset.

Was it not just a few months ago that netizens were up in arms at Gigi Hadid (and rightly so) for squinting her eyes in an apparent effort to mimic Chinese eyes? She was even rumored to have been removed from walking in 2017s Victoria Secret Show in Shanghai amidst calls from netizens to have her banned.

Meanwhile, Amazon and eBay came under fire late last month for selling costumes with kids pictured doing “slant eye” poses. The image was rumored to have gone viral in Chinese groups, with some stating that such images were “totally unacceptable.”

And let’s not forget, in early January a French kindergarten came under fire for a poem in a schoolbook entitled Zhang, My Little Chinese. The poem includes lines such as “Zhang squats down to eat rice,” “his eyes are so small, awfully small,” and “his head is swaying like a ping-pong ball bouncing around.” This was swooped upon by Chinese netizens on Weibo, who made statements such as “We have zero tolerance for things related to national dignity,” and “If they continue to teach and spread such hatred and discrimination, the children will not grow up with healthy minds.”

Perhaps, then, we could more accurately say that it’s less a matter of not understanding racism and more of not recognizing it or not caring about it (or in the case of some, actively enjoying it) when it’s not directed at oneself.

None of the three examples listed above came from official bodies, nor were they seen by over 800 million people. Yet they were still deemed offensive enough to warrant calls for removals, cancellations, and apologies.

Who is to blame?

China Central Television (CCTV) is one of the “central three” (中央三台 Zhōngyāng sān tái) state media outlets in China: the other two are China National Radio and China Radio International, making CCTV the only state television broadcaster in the country.

China Central Television answers to the State Administration of Radio, Film, and Television which in turn is supervised by the State Council. Furthermore, a vice minister of the State Council serves as chairman of CCTV. For context, the State Council is the highest executive organ of state power in China, as well as the highest organ of state administration. Given the high-profile cultural significance of the Spring Festival Gala to Chinese people, it can be safely assumed that all of these government branches sanctioned each detail of the five-hour performance.

So far, we know that the gala was supervised by the State Council. But there are other Chinese organizations that were central to the production of the event. For example, Chinese media company StarTimes Group (四大时代集团 Sì dà shídài jítuán) contributed to the selection of content. StarTimes is a leading TV-provider in the African continent, with 10 million subscribers across 30 countries. Herein lies another hole in the argument that the Chinese authorities were unaware of the racial elements of the play. Surely StarTimes senior level management has acquired a degree of awareness of racial dynamics in the course of its economic dealings in the continent most affected by race. Why didn’t they come forward and take issue with the skit? Why would they pay for the production of a play they knew to be racist?

Black/African Complicity

Life for African students is at times rough in China, yet in a quest to “make it,” those willing to put themselves in compromising positions should consider the communities that they represent. The fact is, most of the cast members in this skit are African. The dancers are African. The train attendants are Kenyan. Some of the main characters are African. Of all those involved in the play, surely they were the most aware of its problematic elements. As a community, we must ask, what happened? Did any of them raise their concerns with the producers? Did they contact their embassies? Or, most disappointingly, were they simply too ambivalent about the skit to take action? In the wake of racist incidents, we must also turn inwards and examine our own complicity. The passivity of the African cast members is no more palatable than that of the Chinese producers.

To what end?

Temporarily leaving racist and insensitive portrayals aside, what is left to speculate on is the intended narrative being created or at least aided by this skit.

Officially it was a testament to China-Africa friendship: references to the Belt and Road Initiative and the new Kenyan rail between Mombasa and Nairobi were used to evidence this. Yet there were some not-so-subtle hints of the underlying nature of the said relationship — or perhaps the way in which China would desire its people to view this relationship. For those familiar with the 2017 Wolf Warrior 2 film, the overarching narrative may seem rather familiar. Ultimately China becomes the savior of the African, and the African becomes reliant on and almost indebted to China.

Interestingly, while the win-win narrative pushed in Chinese media is often criticized by the West because African actors are seen to not win as much as Chinese ones in the exchange, the 同喜同乐 (tóng xǐ tóng lè, i.e., “Celebrate Together”) skit flips this narrative on its head and does away with such concerns completely. In this play, China is the altruistic donor, supporting African infrastructure, education, and health. The skit makes no mention of the economic gains China stands to receive in return. At best it is a one-sided portrayal of international relations, and at worst it calls in a new year with an ego boost for Chinese audiences delivered at the expense of Africans.

Where do we go now?

If there’s one thing we ask the black and African community to take away from this is that we have to be stronger with the counter-narrative we produce. Not just a counter-narrative but to tell our own stories — clearly, an accurate portrayal of us is a reach too far for some external to our community. This work is already underway thanks to groups such as OPOPO, Black in China 黑人在中国, and the Conscious Africans Network (on WeChat).

An apology from CCTV would be ideal, though it is a retroactive gesture and the damage has already been done. For all his faults, Bill Cosby hired an African-American Professor of Psychiatry from Harvard to consult on almost every episode of The Cosby Show to ensure that there wasn’t a single negative stereotype of black people. CCTV should consider similar action. What we need now is a clear signal that this sort of event will never occur again.

In our frustration, we mustn’t allow ourselves to be used as pawns to further agendas against Africa-China relations. As we move into a new era of geopolitics we must be vigilant in the defense of our beloved continent. There are powerful groups that stand to gain from fanning the flames of any growing pains in the Africa-China relationship. Since the gala aired, numerous Western media outlets have jumped at the chance to fit this story into a tight narrative that they have pre-prepared. Africa needs to insulate itself from the meddling hands of those groups and focus on charting a mutually beneficial relationship with China.

Ultimately it is up to us to campaign for our priorities, and in order to do so, we must be clear on what those priorities are and how we intend to achieve them. In the wake of this incident, let’s ask ourselves: what concrete actions do we want to see from Chinese media outlets to ensure that racially charged material isn’t disseminated?

Black Lives China submits the call for CCTV and other Chinese media outlets to create multiple senior level consultancy roles for African media specialists. These experts would be tasked with the responsibility of mainstreaming racial awareness into all content touching upon the African continent. Moving forward, China must incorporate racial awareness and sensitivity to the production of content by all its media outlets. It worked for eight seasons of The Cosby Show, and it could work here too.

This piece originally appears in Black Lives China. Also see:

China’s CCTV Spring Festival Gala included a truly shameless Africa skit, featuring blackface