How ‘self-media’ in China has become a hub for misinformation

As Facebook and Twitter attempt to combat the spread of misinformation, China is having its own “fake news” problem. What can — or should — the government do about it?

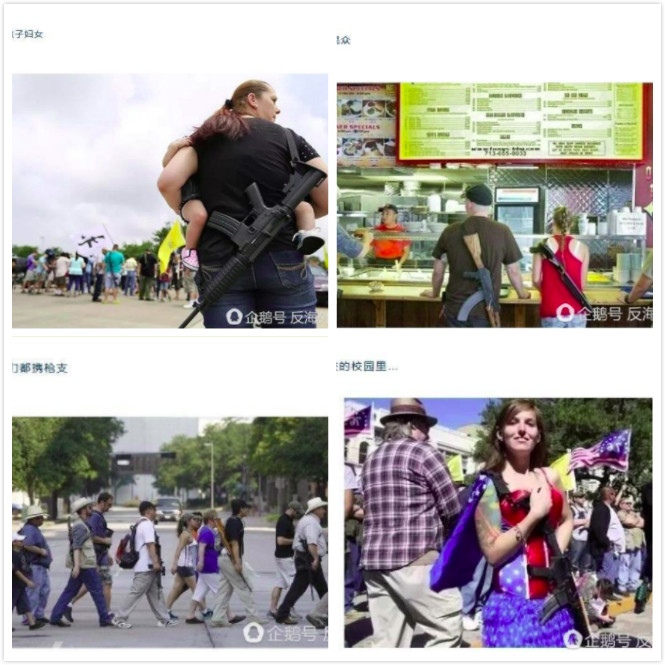

Last October, two days after the deadliest mass shooting in modern U.S. history left 58 dead in Las Vegas, a Chinese self-media publisher released a story on WeChat titled, “After Las Vegas Shooting, People in Texas Bring Guns onto the Street.” It was accompanied by images of moms in supermarkets wearing assault rifles, and others openly carrying firearms in restaurants and on campus. The story was widely circulated, with multiple self-media accounts and major media outlets referencing the story, including giant online news portals like Sohu. China Daily even published a cartoon featuring, if not exactly the same images, precisely the same idea, with the caption: “After worst incident of gun violence ever in the U.S., people start bringing their weapons onto the street.”

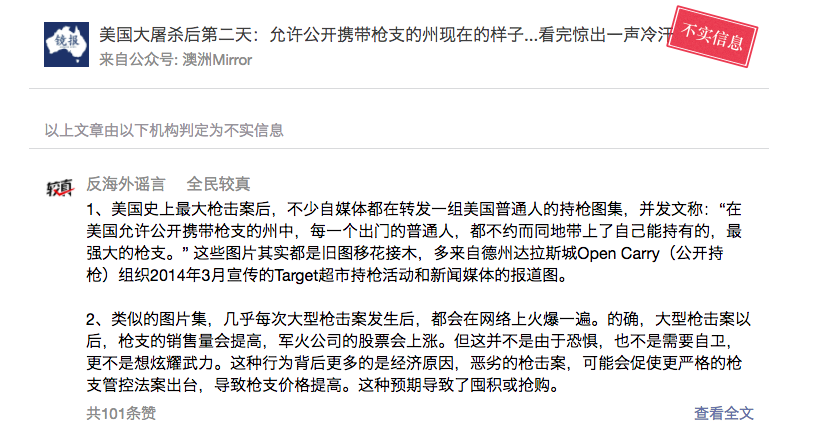

The story, of course, turned out to be entirely false. A self-media account dedicated to debunking falsehood in Chinese-language media, the Center Against Overseas False Rumors (反海外谣言中心 fǎn hǎiwài yáoyán zhōngxīn), revealed that the images were a collection of stock photos. One photo was taken in the Open Carry campaign at Target, Texas in March 2014; another in 2016, after Texas passed a law allowing open carry of handguns. No major international news outlets reported any spike in the open carry of guns in Texas after the Las Vegas shooting.

Troublingly, this is just one of the thousands of international news stories on WeChat that are patently false. As Facebook and Twitter attempt to combat the spread of misinformation, China is having its own “fake news” problem. According to a report on misinformation on WeChat, published by the Sun Yet-sen University in collaboration with WeChat’s security team, 2,175 fake news stories appeared in 2016 alone.

How exactly has Chinese self-media become a hub for misinformation?

Not news outlets, but producing news

In China, self-media (自媒体 zì méitǐ) refers to independently operated social media accounts — on platforms such as WeChat, Weibo, and other smaller ones — usually run by individual users. At least, that’s how it was at the outset. What classifies as “self-media” has expanded, and almost all major news outlets, from the People’s Daily to the Global Times, produce “self-media” content from their own WeChat public accounts. Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of self-media accounts owned by individual users produce their own news, setting them in competition against more credible news agencies. According to the 2017 WeChat Statistics Report, published by WeChat creator Tencent, there are 3.5 million self-media WeChat accounts in existence.

Although there is no official estimate of the number of self-media accounts that focus on international news, the figure is likely to be in the hundreds. On Sina Global’s self-media platform, Global Daily (地球日报 dìqiú rìbào), there are 355 self-media accounts covering international affairs. On U.C., Alibaba’s self-media platform, the viewership for channels covering international news is 10 billion. On Weibo, meanwhile, 700 accounts label themselves as dedicated to international news.

“Though we report news, we are not news outlets,” says Timothy Lin 林国宇, founder of College Daily (北美留学生日报 běiměi liúxuéshēng rìbào), one of the most popular self-media accounts among overseas Chinese students, boasting a following of around 1 million. College Daily’s WeChat posts span translations of foreign news stories, original interviews with Chinese overseas students, and how-to guides (e.g., for paying tuition, etc.). One of its most-read stories in the past year was on a Chinese student at the University of Maryland who reportedly “denigrated China” in her commencement speech by praising the “fresh air of free speech” in the U.S. It caused a huge stir, with some readers accusing the writer of having a clear ideological stance and going against the Chinese student.

“Unlike traditional news outlets, we have to have opinions, though we do not take sides,” argues Peter Li, the journalist at College Daily who penned the controversial piece. “If we are as disinterested, as neutral, as traditional news outlets, why would users read our stories?”

A less-than-rigorous editorial process

When asked if misinformation dominates self-media, Timothy Lin, without hesitation, gave an affirmative: “That is for sure, because now, just one single person can produce news.” He attributes the wide distribution of misinformation through self-media to the lack of a rigorous editorial process. “In traditional newspapers, multiple agents make sure that no factual errors are included. A piece needs to go through journalists, editors, and chief editors in order to get published.”

This less-than-rigorous editorial process can sometimes be linked to mistranslation of stories or content. In one WeChat story found by the Center Against Overseas False Rumors, there was a claim that the death toll from influenza in the U.S. had reached 10 percent. This was a mistranslation of a Daily Mail article in which, as the Center Against Overseas False Rumors puts it, “the editor had mistakenly translated the sentence ‘The illnesses were responsible for 1 in 10 fatalities in the first week of February’ as ‘the death toll reached 10 percent.’”

“Honestly speaking, fact-checking is not highly emphasized in our team, due to time restraints,” says Jeff Liu 刘芳儒, a member of Internationalers (国际电讯 guójì diànxùn), a self-media news feed focused on covering international news. “All we can do is select credible news sources like the BBC to translate, and use as diverse a range of news sources as possible so as to avoid mistakes or bias.”

But in traditional news media, fact-checking is an integral part of the reporting process. “There are strict standards of news production that journalists and editors have to follow,” says Kecheng Fang 方可成, a former journalist at Southern Weekend who is now a PhD candidate at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. He explains that while establishment media might not quote less credible news agencies, self-media would have no compunction about quoting internet users as news sources. Fei Bai 白飞, a former editor at Beijing News who worked at the outlet for 10 years, argues that internal competition among media outlets also plays an overseeing role, since “various media outlets competing against each other means that, once a mistake is made, it will be pointed out immediately by either your competitors or your readers.”

The pursuit of viewership

Although some misinformation may arise from simple mistakes, sometimes outright fabrication may be to blame. “Some self-media sources do not have ethical standards, and the low cost of publishing may also facilitate their ability to spread misinformation,” argues Lao Pao, co-founder of the Center Against Overseas False Rumors. “Besides, the incessant pursuit of viewership prompts self-media to act in an even less responsible way.”

As an example, earlier this month, a huge scandal broke on Weibo when an account with 1 million followers, designed to allow Chinese overseas students to vent their daily grievances, posted a story about a Chinese female student in Germany who claimed she faced harassment from a cult calling itself “Satanism.” The post included drawings of the cult’s symbol that were supposedly left on her doorstep. The story received so much attention that it prompted the Chinese embassy in Munich to investigate. The Weibo account of the Chinese Communist Youth League also responded, posting, “No matter where you are, remember that you are not alone”:

Not long afterwards, the Chinese female student apologized for “causing so much damage with my joke,” and the Weibo account in question apologized for “retweeting the story without doing rigorous fact-checking.”

In this era of self-media, fabrication can sometimes pay. “If you publish a sensationalist rumor, you might get subscriptions to your account tripled; if you have one post that becomes an overnight sensation, that means more than publishing hundreds of stories every year,” explains Duan Lian, another of the co-founders of the Center Against Overseas False Rumors.

“Sensationalist titles and stereotypes can always attract higher viewership, which can be converted into advertising revenues and investment,” says Fang Kecheng, the Annenberg PhD candidate.

In 2014, WeChat opened pay-per-click advertising to businesses, allowing self-media owners to earn money by placing banner advertisements at the bottom of their posts. Zhang Fan 张芃, founder of Here in the UK (英国那些事儿 yīngguó nàxiē shì’er), one of the most notable self-media sources dedicated to international news, revealed in an interview with the New Rank that in 2015, his revenue from pay-per-click advertising topped 1,000 yuan ($158) per day.

Apart from banner advertisements, self-media’s other great potential revenue stream comes from “soft-sell advertisements” — pieces that look like normal stories until the very end, where they start selling a product. On this basis, prominent self-media outlets are attracting investment capital like never before. College Daily received 20 million RMB ($3.2 million) from investors last November, one of which was Tencent, the very creator of WeChat.

But when asked why misinformation does not tarnish the reputation of self-media feeds, Duan Lian, founder of the Center Against Overseas False Rumors, argues that, in the self-media era, readers pay far more attention to the content than the actual source of news. “Rumors are spread, and account-holders get their advertising revenue, but people do not remember where the rumors came from.”

Take the report on Texas and the Las Vegas shooting as an example: Even after the official Tencent fact-checking account debunked the report, the Australian Mirror — the self-media source that first posted the story (which is now deleted) — still enjoys a viewership of around 40,000. Indeed, on the opening page to its account, it boasts of having the largest social media presence among any Chinese-language Australian media source. It declined to comment on whether its factual mistakes have negatively affected its operations.

But not every self-media account thinks a large viewership is the ultimate goal. “An incessant pursuit of large viewership is not sustainable for self-media; what is important is to find your target audience,” says Timothy Lin. He explains that, though the total number of College Daily followers may not be as large as other outlets, his followers are loyal and stay with the site for a long time. Most Chinese overseas students in North America are aware of the account. “Followers who are naturally aligned with our news coverage can become users in our online community,” he adds, since College Daily has just launched a Quora-like platform for Chinese overseas students to share their experiences with others.

Should platforms be trusted to take down content?

That said, self-media accounts with dedicated followers are exactly the type in which readers are less likely to fact-check the stories they read. “As long as you feed your small group of readers what they want to hear, you will be fine,” says Duan Lian. Kong Youxin 孔佑心, a full-time academic and co-founder of the fact-checking platform No Melon Group (反吃瓜联盟 fǎn chī guā liánméng), argues that self-media accounts are now like echo chambers for WeChat users — one can always find “evidence” to support one’s opinion, even if that evidence may be factually wrong. As has been well documented, people often might not even think to question the veracity of what they hear or read — “The tendency to accept our mental representations of things before we assess them may spill over into the process by which we comprehend ideas as well,” the researcher Daniel T. Gilbert wrote in a 1991 paper examining how humans process information. In short, we are more vulnerable than we believe. And as Politico points out, “Sheer repetition of the same lie can eventually mark it as true in our heads. It’s an effect known as illusory truth.”

A research team at MIT, after analyzing some 126,000 stories on Twitter over more than 10 years, found that false information consistently outperforms true information on Twitter in terms of its reach, its influence, and its speed of reproduction. “Ultimately, this is about media literacy,” says Fang Kecheng. “Until a day when people feel naturally repulsed by rumors and sensationalist stories, we need platforms to intervene and penalize self-media that spread misinformation.” Tencent, for its part, launched its official fact-checking account in 2017, and has already formed a partnership with the Center Against Overseas False Rumors. Last year, Tencent closed down 180,000 self-media accounts that post false rumors frequently and intercepted over 500 million rumors.

Apart from social media platforms, the Chinese government itself has launched several campaigns to crack down on internet rumors. As early as 2013, China passed a law stipulating up to three years in prison for anyone who publishes a libelous post that receives more than 500 forwards and 5,000 views. The Paper reported that in 2017, the internet division of Shanghai police investigated 190 internet rumors, giving verbal warnings, imposing fines, and in some cases, imprisonment to the person who spread the rumor.

Of course, people have expressed concern that the fight against fake news can turn into political censorship. A PEN America report last October called it “frightening” that the “sense of alarm over the spread of fraudulent news could be used to legitimize overweening efforts by governments, social media platforms, and others to curb open expression.” (Though the report continued: “That fighting fraudulent news too aggressively can jeopardize free expression does not mean that we shouldn’t fight it at all.”) When China’s anti-rumors law was introduced back in 2013, Weibo users voiced similar concerns about the law being used to silence legitimate questioning of authorities. “Some posts deemed to be defamation may aim to draw attention to problems; if people cannot raise their voice, how can we achieve accountability?” wrote one user.