The mind of Fuller: UK artist creates map of Beijing unlike any you’ve seen

“I didn’t come here because it feels dystopian. They have the opportunity here to tackle some of the things that we got wrong.”

The Wales-born artist known as Fuller is negotiating the sale of one of his artworks over WeChat. We just need to sit down and go through it. He uses the voice record function like a walkie-talkie, speaking numbers in a Dongzhimen cafe amidst buffet-goers chowing down on fried rice. Send me an image and let’s come to a conclusion, he says. Let’s get back to them in 48 hours. When he finally puts his phone down, he rearranges his lanky frame in the small chair and turns to me. “OK,” he nods. “Ready to go.”

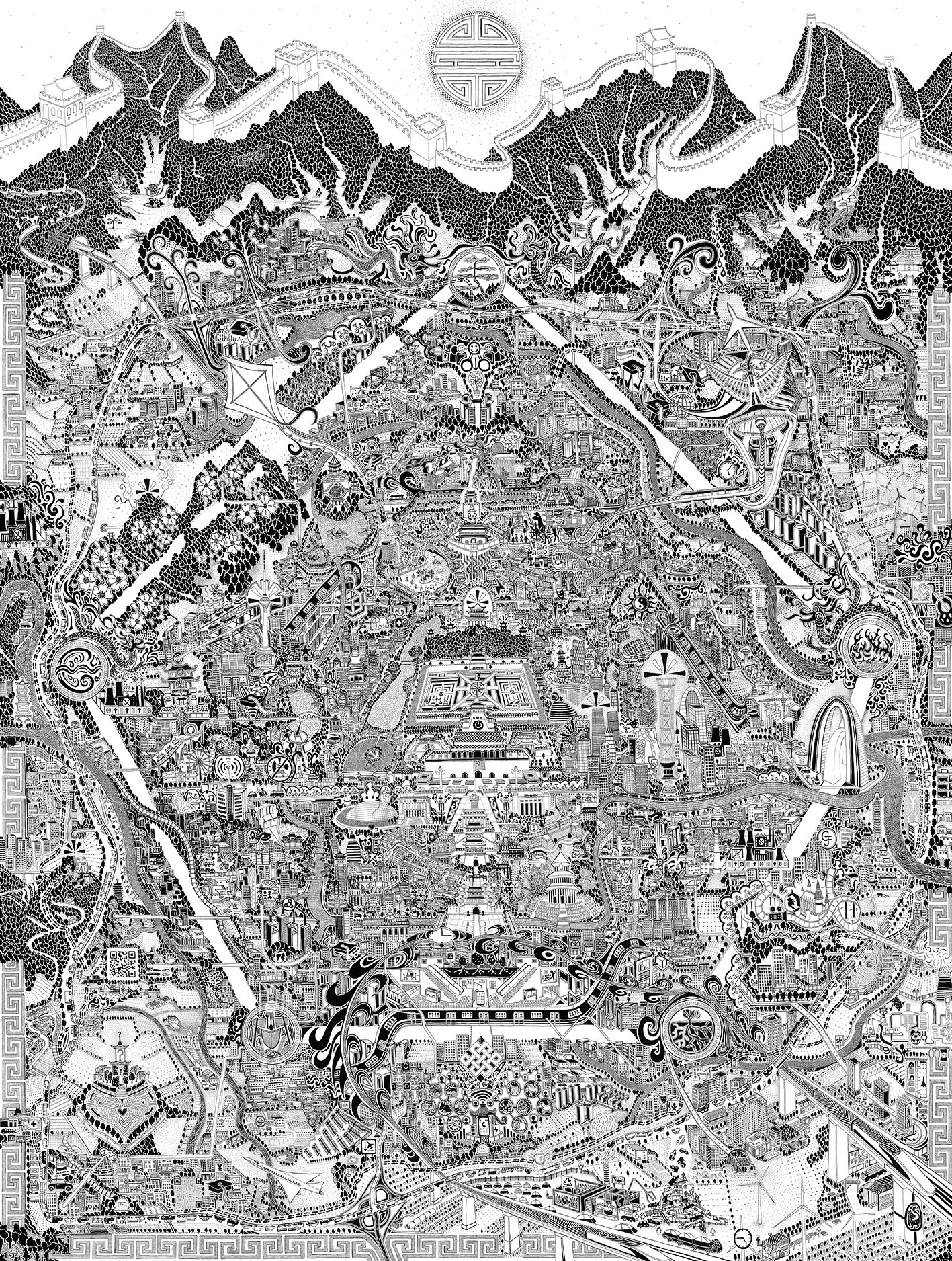

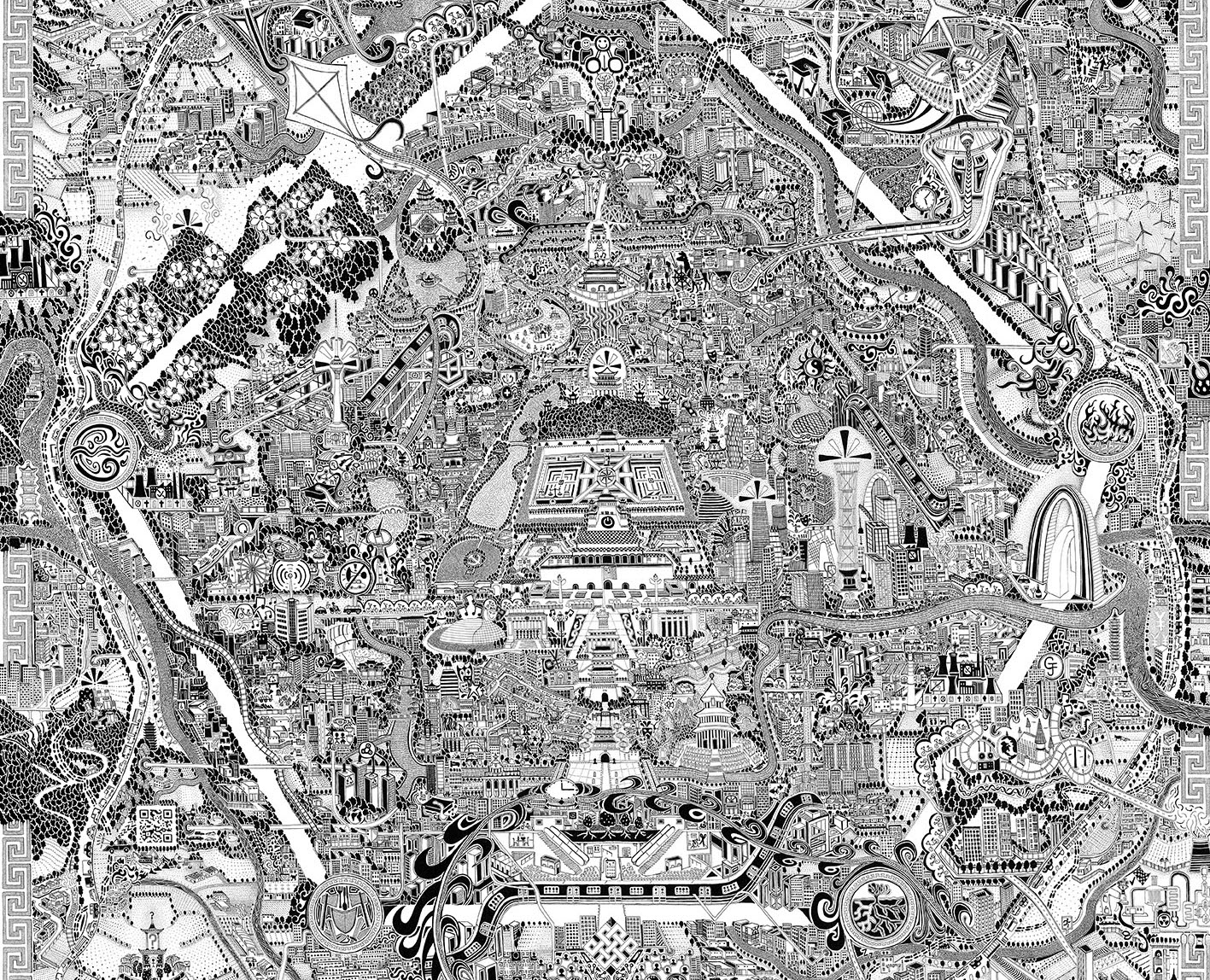

This time last year, Fuller — pen name of Gareth Wood — was walking Beijing’s entire Sixth Ring Road, part of a larger project in which he hoofed it 861 miles (his estimate) around Beijing, much of it in flip-flops. The fruit of that labor was unveiled this past Thursday at an exhibition opening at the Rosewood Hotel in Beijing’s Central Business District: a 1.2- by 1.5-meter map of Beijing — simply called “Beijing” — meticulously drawn with black pigment ink on a cotton museum board over the course of 1,000-plus hours. The Rosewood exhibition also included two prints of the same piece overlaid with gold ink, as well as prints of Fuller’s previous works, maps of Bristol and London (the latter of which is in the British Library in London).

Over the course of our long conversation, Fuller was expansive in his views on technology, data, and society. A former film producer, among many other things, the 37-year-old thinks a lot about the connections between social constructs in different parts of the world, the themes behind the things that people make, individually and collectively. Contemporary artists tend to tightly control the proliferation of visual representations of their work, but guests at the Rosewood opening were free to photograph his work. Fuller thinks a lot about what he wants to put out into the world, and also what he wants to keep to himself.

A lifelong artist, in 2004 Fuller found the confidence, as he describes it, to start mapmaking, which he calls less a profession or production than vocation — the creation of an artifact. His work is a nonlinear spatial catalogue of symbolic geography, at once a visual representation of personal emotional associations and a depiction of the city as iconography.

Fuller’s map of Beijing is currently on display at the National Agricultural Exhibition Center as part of Art Beijing, but only until Wednesday, May 2. Various prints will be on display at the Rosewood until the end of October.

Now in its 13th year, Art Beijing is one of the largest art exhibitions in China focused on “locally based, Asia-oriented” art. Fuller sat down with The China Project ahead of Art Beijing to discuss mapmaking, the universal legibility of symbols, and the appeal of China’s megacity.

The China Project: You’ve been doing map work since 2004, and finally five years ago had the confidence to publish work. What made you decide to publish then?

Fuller: I’ve always had a passion to get a bit lost and go exploring, cycling too far from home, that sort of thing. My mapwork came in 2004 when I was working in London. I had been doing a lot of work with patterns, but my actual mapwork came from my love of exploring. A map of the mind is the way I describe it, because it is a map of my mind.

There are definitely psychological parts of the work. I’ve borrowed cartography as my medium because I’m very aware of how geography works. I’m using the skills from exploring throughout my life and my obsession with culture and society. It allows me to make sense of and define the world, which I find quite chaotic. It allows me to work different topics out in a spatial way.

The idea that I’ve come to in the last couple of years is trying to convey a sense of things, a sense of place. I’m trying to bring that into the pattern work. I’m almost redesigning a city by integrating [among other themes] philosophy that might be ancient to it. For example, in the Beijing piece, I’ve tried to pull in elements of Taoism, to connect these symbols. I’ve put that into the work because it’s a guiding factor to Chinese life. It’s very subliminal, but everyone knows and recognizes these symbols, and today’s culture is still affected by that philosophy.

How do you balance the selection of major, well-known places in the city versus places of emotional significance to you?

I think it kind of boils down to that sense of place. There’s a personal geography there. If I go to Liverpool Street, I’m going to think about the morning when the bombs went off nearby. I remember everybody walking to do their commute because the trains were shut down. I’ve never seen so many people on the streets, and there was a real feeling of unity. It wasn’t contrived, there was nothing else that could be done. If you see something like that, that’s going to result in a very emotive drawing, for the artist and for the viewers, and so that becomes part of the place. [Making the work involves] decisions like that. When I’m walking the Fourth Ring Road in Beijing and I see one of those places that’s got sort of space-age towers that look like they’re about to blast off, I look at it and I love it. [The surroundings may] just be fields and bit of rubbish and some people might look at it and say “there’s nothing there,” but I’ll draw that.

We all create our own landmarks. We all have our own monoliths and ideas. For me it’s partly transcribing my own personal geography and getting that down, but it’s also knowing there’s a collective element. Everyone experiences culture. There’s an almost phenomenological side, it’s a collective idea, it’s something we’re all experiencing, and therefore I hope I can fill in other people’s gaps in their own thoughts with my drawings, because they all trigger different ideas and stories. [I try to] take the time to find out about a place and go through the process of researching it.

There’s so many pockets of society that you just need to make proper time for, and I don’t want to be one of those artists that isn’t doing anything but making art. I can’t really make something unless I’m in it. I can’t draw a city unless I walk around the whole thing.

Speaking about the collective aspect of your work and getting into the flow of representing a collective feeling about a place — how much of that comes from your time there and your research and knowledge of the place? Is there an extra layer of the collective aspect in China?

That’s definitely in the work, almost naturally, because things are interlinked. People recognize not only that there’s a collectivism in Chinese society, but the difference is about substance. The substance of my work is that everything is connected. Maybe this is a difference between Eastern and Western thought, but with the other maps [that I made in England] there was a kind of tendency to categorize things, everything has walls, but in China things are more holistic and dependent on one another.

China lends itself philosophically to more holistic thinking, and society is almost engineered in a collective way. That comes out in the work naturally, because of where I am when I’m drawing. Especially in terms of scale. It happens in a residential block. A lot of people think the residential blocks are all the same, they just go on forever and look very similar, but for me, I notice how this one is different from that one, I just see the scale of the blocks. If I’m walking around one and I can’t get in, and there’s a fence around the whole thing, at first I think this is quite disturbing, but then I realize that’s to keep potential harm out, that’s to do with traditional courtyard living. The iconography of the square forms the sense of community.

Wayfinding in Beijing can definitely be a challenge. Can you talk about your experience walking around Sixth Ring Road? What about Beijing’s specific spatial feeling resonated with you and made you want to walk through it and draw it?

It’s so fundamentally different than what I’m used to that it’s inviting. I’m compelled to draw something I don’t understand. At times it almost feels like a simulation. It’s a lot more practical and functional — that’s where you live, this is where you go [to work or to school]. The land is owned by a central source, so land ownership is different and hasn’t been manicured in the same way [as other places]. It’s not a contrived form of community. If you’re going to live in this kind of apartment block, you will end up forming a community.

In London you see people getting squashed onto the subway car, but here you see people queueing just to get into the subway station. It’s phenomenal. The idea of personal space and boundaries is very different, and how that affects the flow of the city generally is what brought me here, the psychology of the place. I think there’s a different temperament here, where people are more focused on what’s on the inside than what’s on the outside. There’s more of a cycle of tearing down and building new, rather than having something old and keeping it the same forever.

“The appetite for prosperity and abundance is without a doubt intrinsic to Chinese culture.”

I’m drawing the sense of a place, and things that affect that place: history, culture. There are intersections in there, external factors like environmental change and migration. The city is forever in flux. I don’t know what’s right for a megacity like this. Beijing can get bigger and bigger. I think it’s a simulation in terms of the ability to adapt and be resilient. [This ability] is restricted by retrofitting ideas to old things like we do in the West, but here people have space, they’re flexible, the ideas about land ownership aren’t the same as where I come from. This is the wow factor for me in coming here, discovering how we can live differently if we are asked to.

Common sense needs to come into play in planning cities now. Maybe living in a smaller space is a better way to live in an urban environment. Technology, data sharing, distribution of information and energy, these are easier things to implement here, because in a lot of parts [of Beijing] it’s a new city. In the UK, it’s very hard to retrofit stuff. This all affects how I think about what I’m drawing.

I didn’t come here because it feels dystopian. They have the opportunity here to tackle some of the things that we [in the West] got wrong. For example, with the pollution, they’re really starting to tackle it. This sense [of opportunity] comes out in my observations. I’m trying to document a snapshot of what’s happening now in Beijing, and I think maybe I’ve gotten some of it right, and some of it I haven’t.

We spoke earlier about scale as an aspect of China in a lot of different contexts — socially, environmentally, architecturally. How do you render that visually in your work?

Design can make you feel a certain way. When you arrive here at Beijing Capital International Airport, even the airport does it to you. You arrive and you think, “Wow, this is serious.” Everything is big. I want to know why it’s like this. Actually, things have been on a big scale here for hundreds of years. The appetite for prosperity and abundance is without a doubt intrinsic to Chinese culture.

I completely underestimated the scale here. It’s gigantic. There’s thousands of windows in the residential areas, but once I’ve drawn four buildings like that, I’m done, people know what I’m talking about. You underestimate how long it takes to travel places. You travel a short distance and feel like you’ve gone quite far.

I think the scale allows people to feel like they don’t need to go anywhere else. I’ve heard people say they think Beijing isn’t walking-friendly, but this is one of the most walking-friendly cities I’ve been to in my life. Walking-friendly doesn’t mean walking less, walking-friendly means you can actually walk, there’s pavement everywhere, you can ride a bike everywhere. Walking farther for me is maybe better. The scale has its pros and cons.

The scale, how it makes you feel, it’s a play on the spectacular, and a display of “we’re here and we mean it.” You’ve got a lot of people [in China], that is your scale. It’s manpower. To be Chinese is to be part of this huge phenomenon of China. It’s a big thing, it’s moving big things. I think China has used this to its advantage often. The scale can be overwhelming and quite persuasive. Some of the architecture can make you feel inferior, useless.

To produce your work in Bristol and London, in both cases you were living there for a while. How do you see yourself, as a foreigner, making this work here in Beijing? What role do you see yourself and your work playing here?

Am I part of a dialogue, can I be part of a dialogue, am I breaking down cultural barriers, am I doing any of those things? I’ve come here and had an experience and gained some valuable knowledge. I hope that can be shared through my art. I think my work does that. Maps have always been mediums for provoking conversation. I believe art should do that. We should provoke some change in state of mind. I hope my art will be, for those that want it, a way of getting rid of some stereotypes.

I don’t think that I’m saving the world one map at a time or anything, I just think it’s something I can do. I definitely see there’s a cultural exchange that can take place through the work. I think action and application and actually being here are important, as opposed to being an expert from afar who has been here a couple of times. My way of learning is to be out in the world and seeing things.

It doesn’t create a sense of urgency if you’re working out of a box from far away. I don’t want to create division, I want to get people to come to the table to talk, and to not dislike each other, because we’re all human. I think through the work, we can get a little closer together and create a sense of urgency around some of these ideas as well. A lot people are just happy to let things go on for decades. I’m not saying I need radical change tonight, but the first step on all subjects is to get everyone talking. So if I’m part of that dialogue, getting more people together, then that’s better. And if I’m still in my flip-flops somewhere that I probably shouldn’t be, then that’s better for me.

Fuller’s original map, “Beijing,” will be on display at the National Agricultural Exhibition Center as part of Art Beijing until May 2. Prints of the artwork will remain on the second floor of the Rosewood Hotel in Beijing until the end of October.