Mingbai: China’s famous foreigners

Mingbai (明白, meaning “understand”), written by Christian Føhrby and Deng Jie, is a daily newsletter that drops knowledge on things “everyone in China knows, but almost nobody outside the country knows.” Sign up for it at GetMingbai.com.

Mingbai (明白, meaning “understand”), written by Christian Føhrby and Deng Jie, is a daily newsletter that drops knowledge on things “everyone in China knows, but almost nobody outside the country knows.” Sign up for it at GetMingbai.com.

While most Westerners can only name a handful of Chinese historical figures, most people in China are aware of a great cast of Western characters — and often some that are not nearly as famous in their own homelands.

Today, Mingbai zooms in on three foreigners — two Americans and a Canadian — who are known to almost everyone in China, but to surprisingly few outside.

Glenn Cowan 格伦•科恩 (gélún kē’ēn) was one of the main characters in ping-pong diplomacy, which is regarded as one of the most important events leading to the normalization of the U.S.-Chinese relationship after the Cold War.

In 1971, the World Table Tennis Championships was held in Nagoya, Japan. After training overtime one day, this American ping-pong player missed his team bus and was picked up by the Chinese team. The Chinese player Zhuang Zedong 庄则栋 came over and offered him a silk scarf with a picture of the famous Huangshan Mountain. The next day, Cowan returned the favor, giving Zhuang a red, white, and blue t-shirt with the words “Let It Be.”

The entire series of events was obviously highly orchestrated, but that didn’t stop the media from going crazy. The American team was invited to visit China as the first Americans since the revolution in 1949. Premier Zhou Enlai 周恩来 personally greeted them in the Great Hall of the People. And the very next year, President Richard Nixon went to China to negotiate the normalization of relations with Chairman Mao.

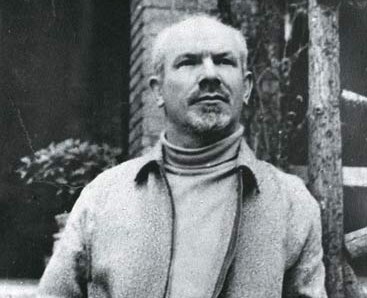

白求恩 (bái qiúēn) is the Chinese name for Norman Bethune, a Canadian so respected in China that numerous medical colleges are named after him.

Born and raised in Canada, Bethune volunteered in World War I and the Spanish Civil War, where he organized mobile blood transfusion facilities and invented many new surgical instruments.

His Communist ideals led him to China in 1938, where he joined Mao Zedong at his revolutionary base at Yan’an, from where the Communists were simultaneously resisting the Japanese invasion and trying to overthrow the Nationalists led by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek.

Bethune is remembered for his selflessness, and for donating his own blood to the wounded. He died of blood poisoning after cutting himself during an operation, and Mao wrote “In memory of Norman Bethune” in his praise. The essay remains core curriculum, memorized by primary school students all over China.

陈纳德 (chén nàdé), also known as Claire Lee Chennault, is one of China’s most well-known war heroes.

Born in Texas, he made his career as a fighter pilot. Although retired early for health reasons, he went to China as a volunteer when the country was invaded by Japan in 1937, reporting to Song Meiling 宋美齡, the wife of President Chiang Kai-shek.

Chennault started training Chinese pilots and soon became the leader of the Flying Tigers, an American air unit credited with popularizing fighter jets painted with shark heads. They took to the skies shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor and played an important part in China’s defense.

“Old Leatherface,” as he was also called, famously married a young journalist from the Chinese news agency who was covering his war effort.

Chennault remains an icon in the history of U.S.-Chinese relations.

Come back next Wednesday for more Mingbai, and remember to sign up for the daily newsletter.