Safety tips are the last thing that Chinese women need after the Didi murder case

Safety tips are the last thing that Chinese women need after the Didi murder case

Li Mingzhu 李明珠 was a 21-year-old flight attendant who was reportedly raped and murdered on May 6 after she hailed a car using Hitch, a ride-share service from Didi Chuxing, China’s biggest on-demand transport company. The Chinese internet responded to her death with a flood of safety tips for women. However, many Chinese women, including me, are wondering why we are the ones who get blamed for our behavior rather than the perpetrators.

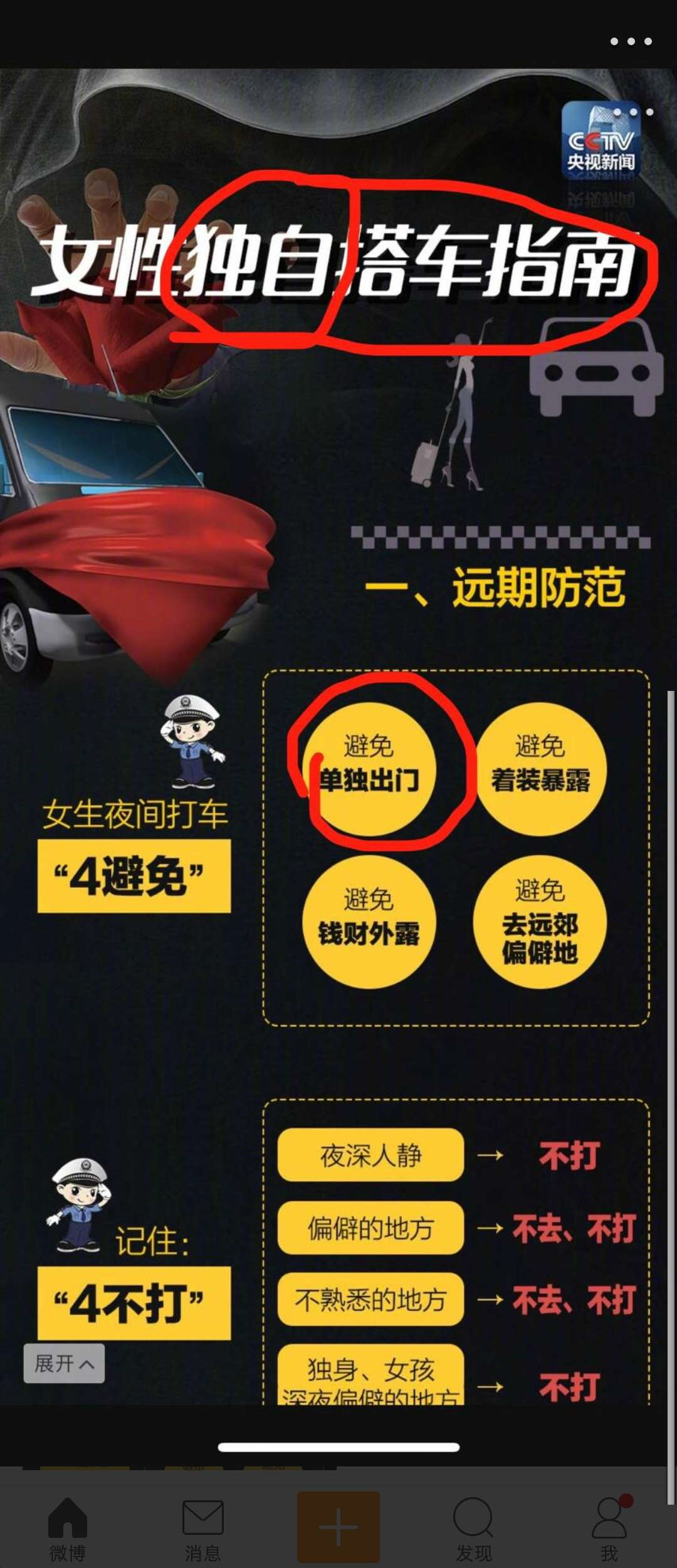

The piece of advice that attracted the most criticism is by Wang Dawei 王大伟, a professor at the Chinese People’s Public Security University. He has established himself as an authoritative voice on crime and security issues and is regularly quoted by well-known media outlets such as the People’s Daily and CCTV.

In a now-deleted Weibo post regarding the Didi case, Wang suggested women should not hail rides under three circumstances — when it’s late at night, when the destination is a remote or unfamiliar location, or when the passenger is a single woman without any companion.

Wang even introduced a score chart for women to assess how much of a danger they face in a certain scenario. According to Wang, women whose “appearances are above the average” or “look wealthy” are mostly likely to fall victim to sexual offenders. And the conclusion that Wang drew from the Didi murder case is that “women should avoid going out at night as much as possible. Don’t take risks.”

The suggestions given by Wang are nothing new or shockingly outrageous. What irritated many Chinese women, though, is the underlying message in Wang’s arguments that Li may have avoided her fate if she had just taken some extra precautions. The general tone adopted by most media outlets was that it is a woman’s responsibility to avoid sexual harassment, even at the cost of their own convenience.

One of the most popular arguments against the epidemic of safety advice (in Chinese) was made by a WeChat public account focusing on gender equality topics, “Orange umbrella” 橙雨伞. The writer, who describes herself as a single female in a major Chinese city, wrote:

For me, Professor Wang’s remarks are worthless nonsense that actually annoys me a lot. As a professor who specializes in security issues, why can’t Wang make some constructive advice based on the reality that women have to deal with? Whether or not we work late is rarely our decision. Not going out at night is such an absurd suggestion. By oversimplifying the problem, Wang seems to have reached a solution. But if we live with his rules, we cannot live normal lives.

Meanwhile, in a stark contrast to the overflow of safety tips for women, the Chinese media downplayed Didi’s responsibility for Li’s murder and overlooked the fact that the Hitch service, which Li used, is alarmingly conducive to sexual harassment.

As some internet users pointed out, in theory, Hitch operates on the idea of matching car owners and passengers who are heading in a similar direction. But the service is putting female passengers in great danger, as many male Didi drivers are using it as a pickup platform where they select potential female riders based on profile pictures and write comments focusing on customers’ appearances on feedback pages.

It’s worth noting that Didi enabled the toxic culture of Hitch by branding the service as a social platform, and marketing it as a way to find romantic partners or even potential hookups. In one Hitch commercial ahead of this year’s Chinese Valentine’s Day (Qixi Festival 七夕节 qīxì jié), the ride-hailing giant wrote, “Let’s date. This is how we should use Hitch.” In another advertising poster, a pretty young lady is seen using the service, with a caption reading, “Not only budget-friendly, but also eye-pleasing.”

In addition, the labels that Hitch allowed drivers to use to review passengers include “sophisticated and sexy,” “beautiful woman,” and even “shall we have a date tonight?” While Didi removed the review system and introduced a range of measures to ensure passengers’ safety, after Li’s murder, much damage has already been done and the multitude of dangerous threats to female riders is showing no signs of diminishing.

On May 17, a woman in Beijing discovered that her Didi driver followed her to her apartment building after the ride concluded. When questioned by police, the stalker admitted his creepy behavior and said that he just wanted to ask for the woman’s WeChat number because “she seems nice.” On May 19, a Didi driver in Hunan Province was exposed in an audio clip offering to pay a female passenger to grope her. Three days later, also in Hunan Province, a woman reported (in Chinese) that her Didi driver deliberately watched pornographic videos while she sat next to him. Afraid of potential confrontation, the woman did not voice her discomfort during the ride and instead discreetly filmed the situation, and later posted the clip to the internet.

While ride-hailing services are lightly regulated, taking a taxi in China as a woman is hardly any safer. Just a few days after the Didi case, a taxi driver in Sichuan was caught on video (in Chinese) pulling down a female passenger’s top when she was making a payment for the ride. The offender was suspended from his job and has received a 10-day detention as punishment.

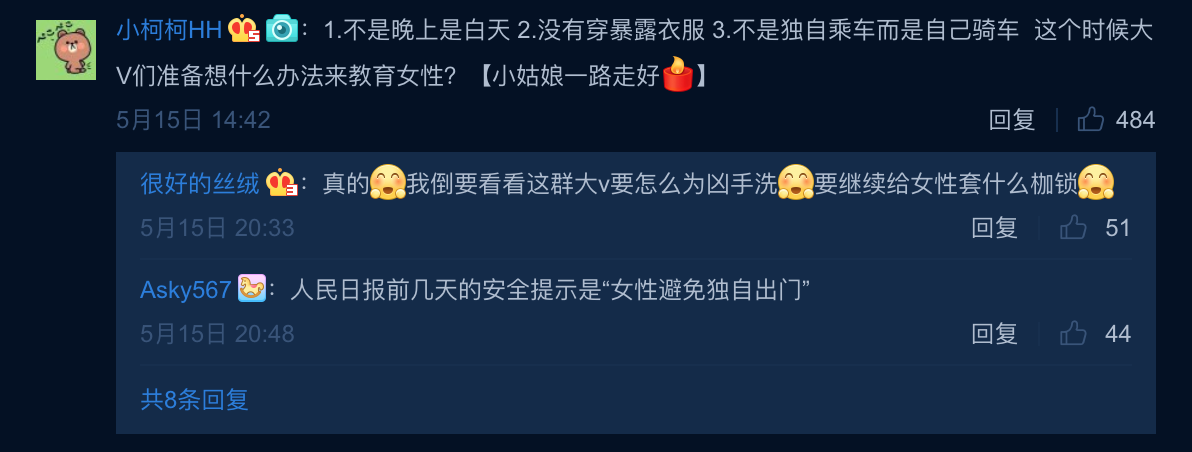

These cases are clear evidence that Wang’s advice is of little use. And when news came that a young woman in Guangdong Province went missing in the morning while biking outside on May 13 and was later found murdered by a 43-year-old man whom she didn’t know, one Weibo user put it (in Chinese): “First of all, this happened during the day. Second, the victim didn’t wear anything revealing. Third, she was on her own bike, not in someone else’s car. What kind of advice will these experts give this time around?”

The sheer absurdity and futility of Wang’s advice also attracted taunting responses from female internet users, as exemplified by the comment below:

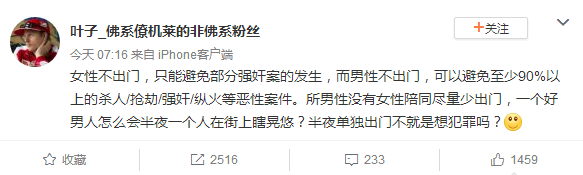

“Some rapes can be prevented if women are not going out, whereas at least 90 percent of pernicious cases of murders, robberies, rapes, and arson can be prevented if men are not going out. I’d like to suggest men go out on the condition of being a woman’s companion. A good man won’t wander on the streets at midnight. If a man is outside alone late at night, he must be thinking of committing some sort of crime.”

In China, women are constantly reminded, both by people around them and by the media, that the violent nature of the world where they live requires extra vigilance for the sake of their safety. For instance, in the wake of Didi’s murder case, many Chinese women have come up with their own ways to protect themselves. Inkstone reported that some have changed their profiles into something less appealing to male drivers. Nevertheless, cautious measures like this can only filter out a small percentage of Didi drivers with ill intentions. Once a woman gets on a ride, she is still a vulnerable target for a sexual predator.

And to exacerbate the problem, on the topic of sexual harassment or attacks, the loudest voices of Chinese men online are those who blame women, specifically, their clothing or behavior. One recent example is a now-scrapped policy (in Chinese) at a university in Hunan Province, where female students were banned from wearing skirts and shorts in the school’s library after some male students complained that such outfits constitute a distraction, even sexual harassment, to them. Using the same logic in these male students’ argument, an internet user jokingly wrote:

“Among so many planets in the universe, why do aliens always want to invade Earth? We human beings should reflect on ourselves instead of placing blame on others. It takes two hands to clap. Is it our insistent attractiveness that draws the attention of aliens?”

The rampant victim-blaming rhetoric, corporate mishandling of sexual harassment allegations, and lack of education for men about how to respect women — or at least do no harm to them — has created a skewed moral environment that constantly poses threats to women’s safety. And yet, the Chinese media and experts like Wang cannot find any solution aside from telling women to stay at home in the evening, as if a dystopian future where no women go out at night is either achievable or desirable.