Inside a Chinese labor camp: Q&A with Leon Lee, director of ‘Letter from Masanjia’

Leon Lee is a Canadian filmmaker whose documentaries focus on human rights issues in China. His debut film, Human Harvest, about China’s illegal organ trade, won the prestigious Peabody Award in 2014. His latest, Letter From Masanjia, tells the story of Sun Yi, who sent a plea for help reportedly while incarcerated in a Chinese labor camp. Sun Yi is a follower of the Falun Gong spiritual movement, labeled by the Chinese government as a cult and banned in 1999. His note made its way 5,000 miles across the Pacific to Julie Keith, a woman in Oregon, via a box of Halloween decorations.

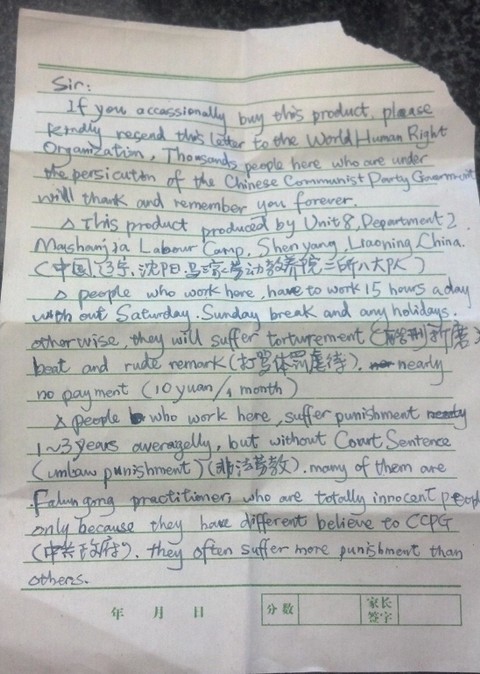

“Sir: If you occasionally buy this product, please kindly resend this letter to the World Human Right Organization,” Sun Yi’s note read, as first detailed in a story by The Oregonian. “Thousands people here who are under the persicution of the Chinese Communist Party Government will thank and remember you forever.”

Keith’s discovery of the note brought international media attention to human rights violations at Chinese prison labor camps. Lee’s film premiered at Toronto’s Hot Docs festival in April. I recently talked to him about Letter from Masanjia and the difficulty of putting it together.

Sophia Yan, The China Project: Can you start from the beginning and tell me how this all started?

Lee: It began with me reading the news about Julie discovering the letter. As someone focusing on China issues, I noticed that the letter was from Masanjia. I know the reputation of Masanjia — this is the notorious labor camp in China. And I thought, if there is a letter coming from Masanjia, there must be an amazing story behind it. Who is this writer? Why does he want to write the letter? How was he able to pull it off? Is he OK? All these questions came out. So I contacted Julie. I interviewed her, and then it took me several years to track down Sun Yi, the letter writer.

[Editor’s Note: When the New York Times first tracked down Sun Yi in 2013, he gave his name as “Mr. Zhang.”]

Some people have wondered if the notes were the work of creative activists who wrote them to shed light on a problem, and that they didn’t actually come from within a prison. What do you have to say to those who are skeptical?

Lee: Well, No. 1, the letter was discovered in this Halloween decoration in Kmart, and when different people, in particular the media, were asking Kmart for a statement, they never questioned that this was actually hidden in their own product.

And also, there are records showing [Sun Yi] was inside the labor camp and in the unit he mentioned. We also compared his [hand]writing, which seems to confirm what he is saying. At least in my mind, there’s no doubt that he was the writer and that the letter was written inside Masanjia and Julie did find it in the headstone he was working on.

If anyone tried to put this [letter] in their packaging in any way, you’d think Kmart would do an investigation. They would at least try to acknowledge that, because that would look far better than sourcing potentially labor-camp-made products. [Kmart] never questioned whether this letter was legit.

What was the conversation like when you first found Sun Yi?

Lee: You see part of the conversation in the film, in the Skype call. Basically, it turned out that he always had this idea of making a film, but he had no idea how to do this. He had seen my work, and he trusted me. But immediately, we realized the risks and also the difficulties.

Because of my previous films, I was not able to return to China safely. He, on the other hand, had no idea how to use a camera. So we had to work together. I provided a list of gear he needed to acquire, we did training over Skype, and he would start shooting stuff, compress, encrypt, and send to me. I would take a look and we would work out a plan for the next day or so. And every once in a while, he would send me a hard drive of the raw footage. He would encrypt them in a way so there was only one chance to unlock it. If I inputted the wrong password, the hard drive would be lost forever. So that’s how we did this. I think we had in total four hard drives. And it was sent to me through an underground network that we developed over the years.

Were the hard drives physically mailed to you in Canada?

Lee: No, not mailed. It was delivered by different people.

It was physically brought over to you?

Lee: Right, because we worried if you mailed it, at any time it could be stopped by customs, or whoever — it’s very risky.

Tell me about yourself. How did you start making these documentaries?

Lee: Well, it began in 2006, when I, again, read a report in a newspaper about forced organ harvesting in China. And I actually didn’t believe it at all. I knew that they had been taking organs from death row inmates for a long time, but this claim that they’re harvesting organs from prisoners, on a large scale, in a hospital that’s not too far away from my hometown — I felt this was not true. But then, I kept thinking — what if it is true? So I started looking into it…and very soon I realized, this is probably true. I thought, maybe many people have the same reaction I did when first hearing the news, so I should try to make a film to allow the viewer to become the investigator and to examine the evidence by themselves, and draw their own conclusion.

It took eight years to complete, because it was so difficult to find people who went to China for transplants willing to appear on camera to talk about their experiences. In the end we were able to find three cases, all from Taiwan. With their story and testimony, I felt the film was complete.

During those eight years, I became so interested in the unknown stories in China. And so many people came to me, in one way or another, telling me their stories. I was both deeply troubled and really moved by their stories. I felt I should continue telling their stories…very rarely do you see films like this. For one reason or another people don’t want to make these kind of films. So, maybe I should do it.

How did you become a filmmaker in the first place?

Lee: I’ve loved watching films since I was young and I know how powerful films can be… I’m mostly self-taught. I did attend seminars and training programs. I read lots of books and studied different things, but I didn’t go to film school.

Why do you think Sun Yi decided not to reveal his identity to the New York Times when they found him in 2013, but to do so many years later?

Lee: He was still very concerned about his own safety, and he wasn’t ready to appear on camera, or reveal his full identity, or to tell his full story. But he certainly wanted to take advantage of this opportunity to tell people what happened. He was still struggling, because he was trying to lay low, not to cause any potential problems for his family. In the end, he decided it was a good compromise to use “Mr. Zhang,” and hopefully that would guarantee safety. And nobody ever did find him after that New York Times article.

To go from choosing not to reveal his identity to doing something so personal, this documentary…what do you think changed for him?

Lee: Good question. Obviously, I can’t speak for him, but my impression was he felt [comfortable], No. 1, working with me, given my track record of Chinese human rights issues, and No. 2, because this was going to be a feature film, it allowed him [the ability] to tell his full story in a way that might create impact, and that was worth the risk. I think that’s how he felt, from my conversation with him.

Sun Yi died in Indonesia (last year). Did you look further into the circumstances of his death?

Lee: Because we don’t have proof, we did not want to speculate on the cause of death. In my view, it’s…certainly there are different possible reasons, but being poisoned is the most likely cause, in my view now. I was aware that someone was trying to convince Sun Yi to stay silent, and this person was very likely a Chinese agent. When I was in Indonesia interviewing him, he was in very good condition health-wise. But then suddenly, almost overnight, he lost his memory, he didn’t even know who I was, and he very quickly died of acute kidney failure, which is consistent with being poisoned. His family went to Indonesia for his funeral. They really wanted an autopsy, but for one reason or another, the authorities quickly cremated his body and no autopsy was performed, so there was no solid proof of what happened. We can only speculate at this point.

Starting with the Hong Kong booksellers, there have been more and more examples of possible interference by Chinese enforcement officers abroad. Have you been worried about something happening to you?

Lee: One, whatever risk I may face, it’s nothing compared to the people in China, the people in my films. They truly risk their lives to tell their story. I’m just a filmmaker. The least I can do is make sure their stories are told. Secondly, I am a Canadian citizen now, living in Canada. While one can never be 100 percent sure of his own safety in this line of work, if I can’t do this in Canada, I won’t be able to do it anywhere, and nobody will be able to do it. Over the years, I only met Sun Yi once, in Indonesia after he escaped, but we had been communicating all the time. He’s like a good, old friend of mine, and he died just like that. So it’s up to me to really make sure his legacy is known, and that’s why I think we really have to do more.

And lastly, perhaps, the only way to eliminate the risks in the long term is to do more. So that hopefully there is change, and there is safety for everybody.

In the film, you show two former guards of the labor camp. Do you know what has happened to them? It’s a big risk for them to come out and speak about this, too.

Lee: To initiate contact in any way would be dangerous. Here’s the thing. It was a big debate with me and Sun Yi on whether to interview them. I was thinking, is this too risky for Sun Yi? Because these people, no matter how good you think they are, they can just call the authorities right away and report you out of fear, or out of other reasons. But Sun Yi felt that they were truly regretful for what they did, and this will be redemption for them. And after the interview, Sun Yi told me they were truly relieved. And they felt good, for the first time in their lives, they had done something right. So in the film, we decided not to use their names, but they come out and testify, of course, taking enormous risk to tell people the truth.

Can you tell me more about Sun Yi? I mean, the kind of process for him. How did he grow while you were working with him, making this film? How did he change? This is certainly not an easy film to make. Did he get worried? Did he ever think about stopping this work?

Lee: Quite the contrary. Quite a few times I felt so frustrated because sometimes, if there were a few instances where I don’t hear from him, and I was scheduled to call, or people telling me something happened to him, I would start to worry.

With the risks escalating, a few times I pushed him to stop. But he was quite optimistic. He was the one always pushing forward, and telling me, “Look, this is no more dangerous than the work I do now…but I want the story to be told, so hopefully there is some change.” He was the one always comforting me, encouraging me to keep going.

He’s so thoughtful…he is just naturally always thinking about other people. That is what really touched me. The other thing is, now living through all this — torture and persecution, family issues — he didn’t turn bitter. When he was recounting the experience of the torture, for example, it was like telling somebody else’s story. It was so peaceful, and there was no resentment toward the torturer or anybody, which I think is true compassion. This is amazing. It’s quite an experience for me to go on this journey with him and get to know him, and learn from him, really.

Sun Yi wrote 20 letters. Only one was publicized — by Julie Keith. What happened to the other 19 letters that he risked his life to write? And what if Julie Keith simply ignored the letter, or didn’t go through the trouble to publicize it? Then what would happen to the hundreds of thousands of people kept in the tiny labor camps? So even a little thing, like what Julie Keith did, sometimes can mean a lot.

Apart from going on a journey with Sun Yi, and learning how remarkable this man is, the other message in this film is to take action. Whatever injustice you experience, if you’re passionate about, do something about it, instead of only talking about it. [If you only talk about it], you never know. You never know what’s going to happen.

Film Friday is The China Project’s film recommendation column. Have a recommendation? Get in touch: editors@thechinaproject.com