How do you say “maternal grandmother” in Chinese? Depends who you ask

Not unlike “coke,” “pop,” and “soda” — words for the same soft drink that have divided America — the different Mandarin terms for “maternal grandmother” is also dividing China, in a manner of speaking. A viral WeChat article with more than 100,000 views recently exposed a Shanghai publisher’s removal of the vernacular term for “maternal grandmother” from an elementary school textbook, with many locals calling it an affront to native Shanghai culture.

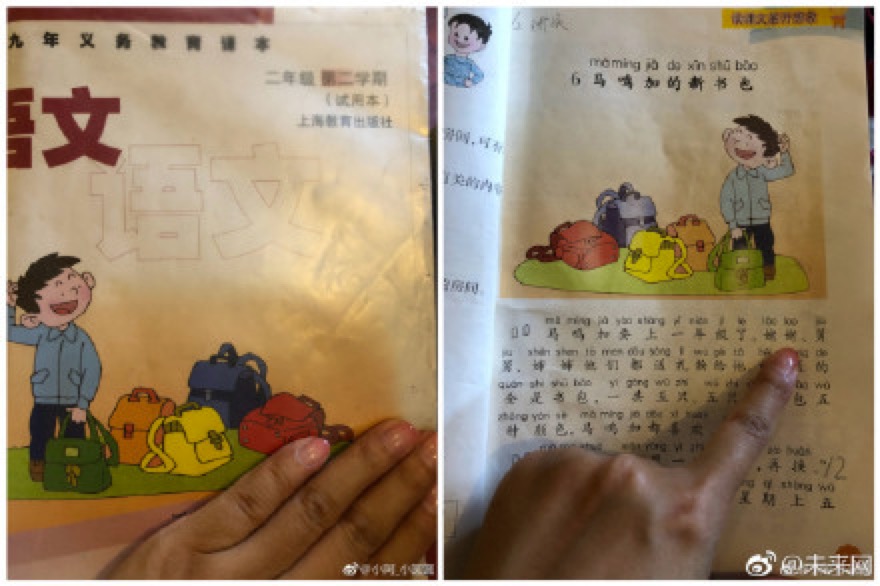

In the second-grade textbook, which goes by the generic name Language (语文 yǔwén) and is published by the state-owned Shanghai Education Publishing House, there is an essay titled “Morning Glory” (打碗碗花 dǎ wǎn wǎn huā) by Li Tianfang 李天芳. In that essay, the colloquial term for “maternal grandmother” — wàipó 外婆, widely used in southern China, including Shanghai — has been changed to lǎolao 姥姥, which is more commonly used in northern China.

The textbook is used in many public elementary schools in Shanghai. In February 2017, Shanghai’s Board of Education responded to a complaint regarding the issue. The board wrote that according to the Contemporary Chinese Dictionary (现代汉语词典 xiàndài hànyǔ cídiǎn), the northern term “lǎolao 姥姥” is a colloquial word in standard Mandarin, while “wàipó 外婆” is used only in native dialects. “Shanghai is an international metropolis with a reformed economy,” the board said. “Since many of the people here are from different parts of the country, immersing in an environment with different languages helps us build a diverse, welcoming, open, and harmonious society.”

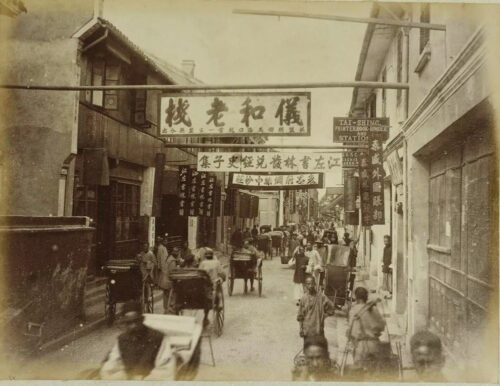

In 1955, the Chinese state officially established standards for Mandarin — 普通话 (pǔtōnghuà) — based on northern Chinese dialects in an effort to create a common tongue for the linguistically diverse country. Since then, China’s government has used linguistic uniformity as a political tool to centralize power at the expense of ethnic and cultural heritages. The most controversial example is Beijing’s pushing of putonghua education in Hong Kong — where Cantonese is seen as a unique cultural identity — to assimilate youths into mainland Chinese society.

Luwei Rose Luqiu, a well-known Hong Kong journalist, stressed that removing dialects from textbooks abolishes cultural diversity, and is a form of cultural dominance. “Installing language policies — which includes standardizing the language used in classrooms, publications, and public media — is a political issue,” she argued on Weibo, on which she is an opinion leader with more than 4 million followers.

Like Hong Kong’s Cantonese defenders, Shanghai natives also take pride in their local language, Shanghainese. The city has discouraged the use of Shanghainese in schools since 1992, leading to Shanghai students being increasingly unable to speak the language fluently. In recent years, Mandarin radio and television programs have increasingly replaced Shanghainese ones.

UPDATE, 6/24: On June 23, the Shanghai Board of Education and the Shanghai Education Publishing House promised to reverse the edit, and apologized for modifying the original text and disrespecting native dialects.

Photo by Raluca Georgescu