Chinese Corner: Dead men tell no tales, and the true story of the cancer drug gang

Chinese Corner: Dead men tell no tales, and the true story of the cancer drug gang

The true story of the cancer drug gang

令人生疑的“中国药神”

By 靳锦 | GQ报道

July 5, 2018

After textile trader Lu Yong 陆勇 was diagnosed with leukemia, he bankrupted himself by spending more than $80,000 on government-approved medication. Broke and desperate, he began smuggling a vastly cheaper substitute from India, and selling it to other patients. In 2014, he was arrested on charge of selling counterfeit drugs, which prompted hundreds of leukemia sufferers that he had helped to petition for his release. One year later, he was freed without penalty.

Now his story is being told in Dying To Survive (我不是药神 wǒ bùshì yào shén), an unconventional summer blockbuster (see our columnist Pang Chieh-Ho’s review) that has been scoring highly positive reviews (in Chinese). The China Project’s own movie columnist Pang-Chieh Ho said Dying To Survive might be China’s best movie of the year. But separating fact from fiction, many people are asking: Is there more to his story that has not been shown on the big screen?

There certainly is: In this feature story 令人生疑的“中国药神”, Jin Jing 靳锦 at GQ Reporting (GQ 报道) reports that Lu is now promoting another alternative medication produced by an Indian pharmaceutical firm. To Jin, this seems rather sketchy, but Lu himself addresses criticism that he was exploiting other patients for profit in this interview with the Beijing News.

Other articles connected to Dying To Survive and the issues it raises dig deeper into China’s long-standing failure to offer affordable and effective medications for deadly diseases such as leukemia:

- In this article published by the Southern Weekly 南方周末, reporter Ma Suping 马肃平 shows how difficult it is for China to reform its regulation of drugs due to conflicts of interest in the pharmaceutical industry.

- Gao Long 高龙 at Guyu Lab 谷雨实验室 focuses on a group of Chinese cancer patients who travel to India regularly to buy illegal drugs.

- Blogger Xu Ziming 徐子铭 argues that the generic drugs market in China is still loosely-regulated and severely underdeveloped.

See also:

-

Opinion: China must wake up to injustice of high drug prices / Caixin (paywall)

“Some laws managing the pharmaceutical industry are contrary to the goal of saving lives, and it is time to rethink those rules.” -

Film applauded for frank portrayal of generic-drug smuggling case / Caixin (paywall)

“‘Dying to Survive’ tells the story of an unsuccessful merchant asked by a leukemia patient to smuggle in cheap generic drugs from India.” -

China’s next box office hit? A dark comedy about smuggling cancer drugs from India/ Quartz

“‘Over the years since I became ill, the drugs have cost me my home and bled my family dry. Sir, can you tell me which family doesn’t have a patient, and can you guarantee that you’ll have a lifetime free of illness?’” - Chinese buyout of Australian cancer treatment developer approved / Caixin

- Are China’s drug price controls failing?; Import tariffs on cancer drugs cut to zero / The China Project

The life of ‘Stephen Chow on Kuaishou’

三炮们不想打工了

By 郭路瑶 | 冰点周刊

July 5, 2018

In 2015, 18-year-old high school dropout San Pao 三炮 was working at a packaging factory in Guangzhou. He borrowed money to buy a iPhone 5s, which allowed him to publish clips on Kuaishou, a Chinese video-sharing and live-streaming app. San quickly gained attention for his videos where he showed off his motorcycle or got kicked into the water.

Advertisers began to pay him small sums to place commercials in his clips, and he began to see an alternative to his factory life. In one of the most viewed videos on the Kuaishou app, a guy says to his phone camera, “I will never ever work for anyone.” San was inspired. With a determination to develop a fanbase on the app, he left his job, moved back to his hometown in Guangxi, and started producing creative videos that, according to his followers, display a similar sense of humor of Chinese comedian 周星驰 Stephen Chow.

San now has a staggering 6 million followers and is contemplating how to transform his spectacular popularity on Kuaishou into more cash.

Dead men tell no tales: the narrative of the sent-down youth

一场没有人愿意张扬的学术研讨会,和一个日渐紧迫的话题

By 陈莉雅 | 好奇心日报

July 5, 2018

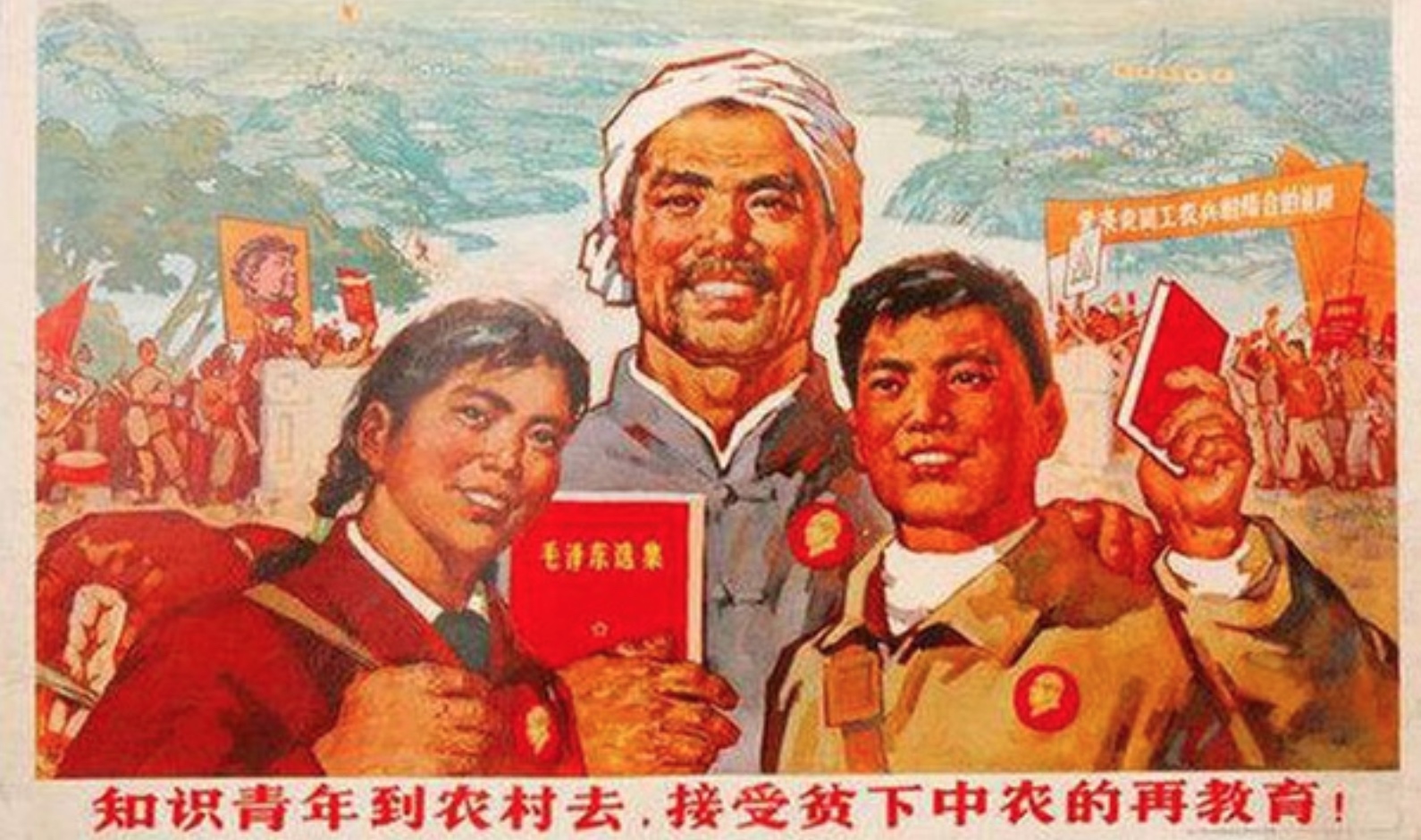

From 1967 to 1979, on Mao Zedong’s order, more than 16 million educated youth in urban China were relocated to rural areas during the Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside Movement (上山下乡运动 shàngshānxiàxiāngyùndòng). They were called “Zhiqing” (知青 zhīqīng), short for “educated youth.” (知识青年 zhīshiqīngnián) The term has been translated into English variously as sent-down, rusticated, or educated youth (see Wikipedia entry).

Decades later, the phenomenon remains controversial. What was the real motive behind the movement? Is it justifiable to relocate people against their will? And more importantly, who owns the narrative of this event?

In a seminar last month, these issues were hotly debated among history professors and Zhiqing, who often feel their voices are significantly downplayed while attending academic meetings. Zhu Shenglei 朱盛镭, a Shanghai native who spent 7 years in Shanxi in the 1970s, told Q Daily, “Some of their thoughts are absolutely wrong. Fortunately, we are still alive, because dead men tell no tales.”

These stores are cool, regardless of what’s inside

中华土味店铺大赏

By 看客inSight

July 4, 2018

An eye-catching name can be essential to the success of a new small business in China. This rings true especially when the business itself is not so exciting. A good store name is supposed to be witty, concise, and comprehensible. Ideally, it showcases the owner’s personality.

In this photo essay, the author puts together a gallery of creative shop signs that he has encountered since 2016. By scrolling through these photos, you can tell that restaurant owners prefer to take a direct approach to lure customers in, often by naming the stores something along the lines of, “You hungry?” Salons in rural China have a penchant for calling themselves “modern” or “fashionable.” Meanwhile, business owners in Yiwu are obsessed with inserting words like “wealth” and “affluence” into their stores’ names.