Five essential Chinese silent films

Politics, revolution, bloodshed, prostitution, suicide, feminism (before it was defined as such): Chinese films of the 1920s and ’30s were forward-thinking and shocking in ways that remain controversial to this day. See for yourself —

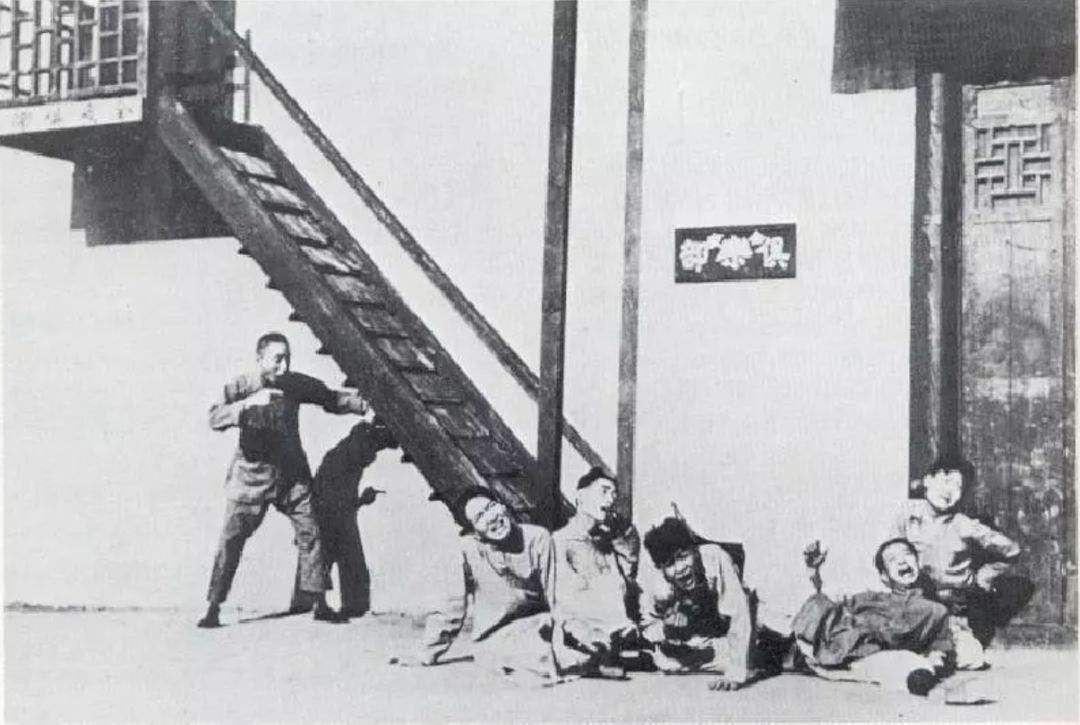

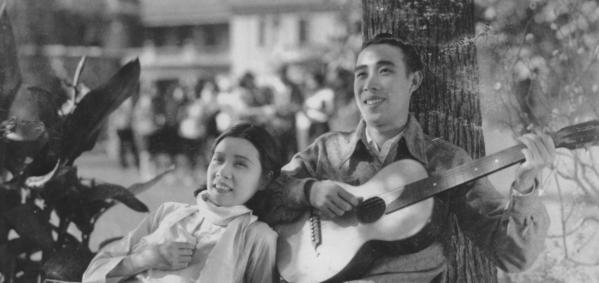

(Top images, clockwise from left corner: Laborer’s Love, The Goddess, New Women, Spring Silkworms, Little Toys)

When film first arrived on Chinese shores in the late 1890s, the industry was dominated by foreigners. The theaters were largely owned by non-Chinese, and the movies shown were Western in origin. Some Chinese-owned movie companies began to pop up in the 1910s, but it really wasn’t until the early 1920s that native filmmakers started seeing any success. Though influenced by the West, these filmmakers tapped into the culture of their own country, making comedies, literary adaptations, wuxia (“martial heroes”), and even dramatizations of real-life murder cases.

By the 1930s, the Chinese movie industry had entered a golden age of sorts, inspired by the ideals and politics of the May Fourth Movement. The hub of all this creativity was Shanghai, which would host the three biggest production companies of the time: Lianhua, Mingxing, and Tianyi. Interestingly, while the United States eagerly jumped onto “talkies,” Chinese filmmakers — for financial and technical reasons — continued to experiment with silent films during the time.

Of course, no golden age can last forever, and this era came to a screeching halt with the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), which saw the literal destruction of the Chinese movie industry. Unfortunately, as is the case with most other countries’ movies from the silent period, the great bulk of Chinese silent films have been destroyed or lost. Here are five essential films, however, that can still be watched today, via home video and streaming.

1. Laborer’s Love 劳工之爱情 (1922)

Dir. Zhang Shichuan 张石川

Zhang Shichuan, a key early Chinese director, got into the movie business working for the American-owned Asia Film Company during the 1910s. Along with his collaborator Zheng Zhengqiu 郑正秋, Zhang and Zheng are considered the founding fathers of Chinese film. Together, they created The Difficult Couple (1913), a now lost short about arranged marriage that was the first Chinese feature film.

In the early ’20s, Zhang and Zheng became two of the founders of the Mingxing Film Company, one of the companies that would lead the Chinese silent film industry. Initially, Mingxing had a rocky beginning, and its first three movies failed to make much of a splash. They were all American-style slapstick shorts, and only the second of the trilogy, Laborer’s Love (1922), has survived.

Even though its contemporary reception was indifferent, “Laborer’s Love” is actually a pretty fun movie. It follows an unemployed carpenter named Zheng, who’s taken to selling fruit for work. When Zheng wants to marry the daughter of a struggling doctor, the doctor will only accept his request if Zheng can improve his business. Zheng’s solution? Hurt as many people as possible. It’s a fun and simple story, and because it’s the earliest extant Chinese film, Laborer’s Love makes for an interesting historical document as well.

Where to watch it: There are several versions on YouTube, but I recommend this one:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vZm9Mo3XQCE

2. Little Toys 小玩意 (1933)

Dir. Sun Yu 孙瑜

After a decade of getting down the basics, Chinese filmmakers made some genuine masterpieces in the 1930s. Chinese theater and Hollywood still had a big influence on movies from this period, but the earlier May Fourth Movement, and contemporary Japanese aggression in China, also shaped the scene. A number of filmmakers included left-wing themes in their work, criticizing imperialism and traditionalism, and focusing on realistic portrayals of ordinary people, like peasants and the urban poor.

The Lianhua Film Company, founded by Hong Konger Luo Mingyou 罗明佑 in 1930, was a pioneer of this new, socially conscious style. At a time when foreign movies were flooding the Chinese market, Lianhua was established to compete with the best of Hollywood, producing some very fine actors, directors, and screenwriters in the process. Its Little Toys is a great showcase, for example, of two legendary actresses of the time: Li Lili 黎莉莉 and Ruan Lingyu 阮玲玉. Li, a dancer and singer, often portrayed energetic, beautiful country girls. Her co-star Ruan is probably the best-known Chinese actress of her generation; she starred in many classic movies, and her tragic life was the subject of the critically acclaimed Hong Kong movie Center Stage.

In Little Toys, Ruan played the role of a mother named Sister Ye, and Li played her daughter, Zhuer. (Funny enough, in real life, Ruan was only five years younger than Li.) The family’s village is known for its toy-making, and Sister Ye is the village’s most admired toymaker. It sounds innocent enough, but Little Toys ultimately drags Sister Ye through hell and back, destroying her village and tearing her family apart. (And that’s just the first act!) At the end, Sister Ye is left in rags, pleading to the people around her that China must fight back against Japan. It’s a devastating movie, and director Sun Yu would later revisit its anti-imperialist message in the equally amazing The Big Road (1934), a movie about six patriots who work to build a road for the Chinese army.

Where to watch it: Unfortunately, Little Toys isn’t the easiest movie to find on the English-speaking part of the web. This copy on Tencent Video here, however, has English intertitles.

3. Spring Silkworms 春蚕 (1933)

Dir. Cheng Bugao 程步高

While there were plenty of actresses during China’s silent era, there were very few female screenwriters. Ai Xia 艾霞, both an actress and a writer, was a rare exception. Born to a middle-class family, and college-educated, Ai headed for the movie industry in Shanghai after her parents tried forcing her into an arranged marriage. Ai fashioned herself as a modern, independent woman, and her novel A Woman of Today championed these values. In 1933, Ai adapted and starred in a movie based on her work, though it hasn’t survived to the present day.

Spring Silkworms — adapted from a novella by the famous writer Mao Dun 茅盾 — wasn’t written by Ai Xia, but it does include a performance by her. Shot in an interesting documentary-like style, Spring Silkworms is the story of a poor silk farmer named Tongbao, who lives in the province of Zhejiang. Tongbao and his family work hard, but they’re constantly sabotaged, sometimes by forces they can’t control — like a fight between warlords causing a market to close down — and more mundane things, like a woman (played by Ai) who throws some of the family’s silkworms into a river. As a whole, the movie’s an attack on imperialism of the economic variety, showing how cheap foreign goods swamped the Chinese market of the time and hurt domestic workers.

Sadly, Ai Xia didn’t live much longer after the release of Spring Silkworms. The film adaptation of A Woman of Today was released the same year, and heavily criticized for its revolutionary themes. The savage criticism really got to Ai Xia — on February 1934, at the age of only 21, she killed herself by eating raw opium.

Where to watch it: Spring Silkworms can also be tricky to find, though there is a version on Youku and YouTube:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mTD_98eqQbU

4. The Goddess 神女 (1934)

Dir. Wu Yonggang 吴永刚

Back in the 1920s, as a young man commuting between art school and his job as an art designer, Wu Yonggang would regularly see prostitutes on the streets of Shanghai. Wu felt bad for being unable to help these women, but wanted to make an oil painting as a way to talk about the issue. He never got a chance to make the painting, but his impressive debut as a director, The Goddess, would be his contribution to the national conversation.

The Goddess stars Ruan Lingyu as a nameless woman trying to raise her little boy. She’ll do anything for her son, and to make ends meet, works as a prostitute in Shanghai. One night, during a police raid, the mother hides in a gambler’s house. He demands that the mother become his property in return, acting as her pimp and taking her money. Hoping her son can have a better life, the mother sets some money aside so her boy can go to school. Soon, the parents of the boy’s classmates catch wind of his mother’s occupation, and the school board is pressured to expel him.

As a last resort, the mother plans to run away from Shanghai with her son, but things take a turn for the worse when her pimp steals her savings. Though The Goddess was made over 80 years ago, the movie’s treatment of prostitution isn’t outdated or insensitive. In fact, one notable film scholar, Tony Rayns, wrote that The Goddess was the first movie made “anywhere in the world to deal with prostitution without equating it with moral degradation.” Ruan’s character is a strong, sympathetic woman, and her performance is so haunting that it’s really quite the shame The Goddess isn’t better known outside of China.

Where to watch it: Luckily, The Goddess can be viewed on YouTube, downloaded from Archive.org, or bought on DVD from Amazon.

5. New Women 新女性 (1935)

Dir. Cai Chusheng 蔡楚生

Possibly the most controversial film on this list, due to the events that followed it, New Women was inspired by the life and death of Ai Xia. In this movie, Ruan Lingyu plays a Shanghai music teacher named Wei Ming. Wei wants to become an author, and when one of her books is accepted for publication, it seems like her dreams are about to come true. But then Wei rejects the advances of a man named Dr. Wang, a powerful member of the local school board, and everything starts tumbling down.

Using his influence, Dr. Wang manages to get Wei fired from her teaching job. Wei falls back on her publisher, and then a journalist, but she rejects them after they hit on her. With bills to pay, and a sick daughter, Wei has no choice but to become a prostitute. Without giving too much away, Ruan’s character faces an even gloomier end than the one in The Goddess, leading Wei Ming to commit suicide.

On its opening in theaters, New Women was condemned by the press for its seedy depiction of journalists and the treatment of its main character, a modern woman who meets a terrible end. Eventually, the outlash got so bad that the production company that made it (Lianhua) made a formal apology. At the same time, while Ruan Lingyu was being slammed for her role of Wei Ming, journalists snooped through her private life, writing sensational articles about court cases — filed by two separate lovers — that accused her of adultery and theft.

On March 8, 1935, Ruan Lingyu was found dead. Eerily, just as her character did in New Women, Ruan killed herself by taking an overdose of sleeping pills. The country’s grief at the loss of its biggest star was tremendous; more than 100,000 people showed up to Ruan’s funeral procession, held in Shanghai. The procession spanned the length of three miles, and three devastated fans even committed suicide themselves. Ruan’s farewell was, as the New York Times called it, “The most spectacular funeral of the century.”

Where to watch it: The Internet Archive has a copy of New Women here, and there’s also a DVD on Amazon. Both copies have dubbed intertitles in Chinese.

Gifs via Silents, Please!

Film Friday is The China Project’s film recommendation column. Have a recommendation? Get in touch: editors@thechinaproject.com