5 great Chinese movies from the Second Golden Age

The Second Golden Age of Chinese film, short-lived as it was, saw some of China’s best directors, actors, and movie studios produce powerful, enduring works of cinema that examined how the war with Japan and the country’s civil war affected the lives of ordinary people. They are artful and realistic, comic and tragic.

Here are five that have stood the test of time.

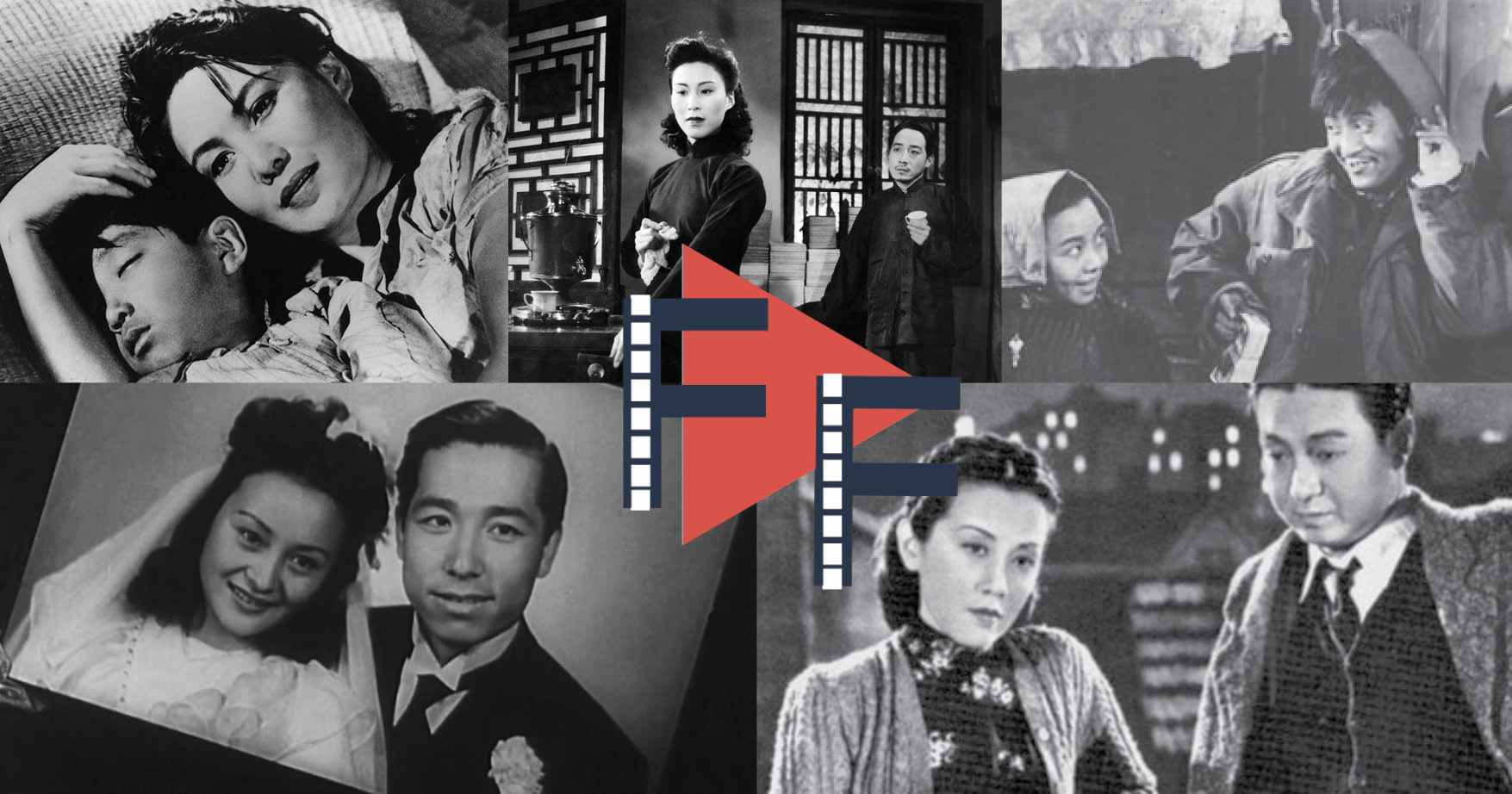

(Top images, clockwise from left corner: The Spring River Flows East, Spring in a Small Town, Crows and Sparrows, Myriad of Lights, This Life of Mine)

In the first half of the 20th century, the Chinese film industry was largely centered in Shanghai. During the 1930s, Chinese filmmakers in the city made a string of classics in an era now remembered as the First Golden Age. With the coming of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), Shanghai’s incredible film industry fell apart, forcing important film studios like Lianhua and Mingxing to close, and sending the city’s talent scrambling to take cover in places like Chongqing and Hong Kong. While there were still movies being made during the time, censorship and the dark political climate stifled creativity and quality.

When the war ended, and fighting resumed between the Communists and Nationalists, the film industry in Shanghai experienced a remarkable revival. Known as the Second Golden Age, the best filmmakers of the time made powerful movies examining how the war with Japan and the country’s civil war affected the lives of ordinary people. Some of these filmmakers were veterans from the First Golden Age, and many were also leftists who used their work to criticize the Nationalist government.

The year 1949 might be counted as the end of the Second Golden Age, but 1951 could also be a good contender. In that year, the Communist Party tightened its grip on the film industry, banning not only movies from America and Hong Kong, but any Shanghai movie made before 1949. In response to director Sun Yu 孙瑜 and his The Life of Wu Xun 武训传, a movie Mao Zedong personally condemned, a film committee was even established to censor scripts. Within a few years, the biggest studios on the mainland were closed and nationalized, and the government instead promoted Soviet-style social realism. Still, while the Second Golden Age might have been brief, it produced some of the best Chinese movies of all-time. Listed below are five great movies of the period, available in the United States via home video and streaming.

The Spring River Flows East 一江春水向东流 (1947)

Dir. Zheng Junli 郑君里 and Cai Chusheng 蔡楚生

Spanning more than three hours, and set before, during, and after the war with Japan, The Spring River Flows East is sometimes compared to Gone with the Wind for its sheer epic scale and cultural impact. During its three-month run in Shanghai theaters, the movie sold more than 700,000 tickets, a milestone for the time and over 14% of the city’s population. Even after its original release, the movie was so popular that people were willing to walk miles braving wind and rain in order to catch a screening.

The brainchild of directors and screenwriters Zheng Junli and Cai Chusheng, The Spring River Flows East is divided into two parts. The first part, “Eight War-Torn Years” 八年离乱, opens in 1931, when the idealistic teacher Zhang Zhongliang marries a factory worker named Sufen. Zhongliang is an active campaigner against the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, and when the fighting comes to Shanghai, he decides to join the war effort, leaving Sufen and the rest of his family behind.

By the second part, “The Dawn” 天亮前后, Zhongliang has turned his back on his family and ideals. He becomes a businessman in Nationalist-controlled Chongqing, marrying another woman and keeping a mistress on the side. His family, meanwhile, suffers in poverty. Ironically, Sufen has no choice but to work as a servant for the woman who turns out to be Zhongliang’s mistress. After years and years apart, Sufen and Zhongliang finally meet again at a party, where Zhongliang has to confront the past he’s tried to ignore. Seven decades after its initial release, The Spring River Flows East still packs quite the emotional punch. There are a handful of scenes — including the shocking ending of the second part — that are simply unforgettable.

Where to watch it: Cinema Epoch has released the movie on DVD, and it’s also available to stream on Amazon.

Myriad of Lights 万家灯火 (1948)

Dir. Shen Fu 沈浮

With the end of the Second Sino-Japanese War, Shanghainese hoping that their city would return to normalcy were struck by inflation and a housing shortage. During this time, the Kunlun Film Company portrayed these pressing issues in a string of movies that depicted the less fortunate of Shanghai society. These movies were melodramatic and political in flavor, in part because Kunlun had merged with the New Lianhua Film Society, the successor to the legendary Lianhua Film Company of the 1930s.

In 1948, Kunlun released Myriad of Lights, a drama written and directed by Shen Fu, an old Lianhua veteran. The movie tells the story of a Shanghai office worker named Hu Zhiqing, who lives in a one-room apartment with his pregnant wife, daughter, and cousin. Like much of the rest of Shanghai, Zhiqing’s fallen on hard times, but he writes letters to his mom raving about life in the city anyway. Encouraged by his letters, the rest of Zhiqing’s family — his mom, brother, sister-in-law, and their children — leave the countryside and pack their bags for their relative’s apartment.

Zhiqing’s salary can barely provide for four people, let alone another five. He tries to be accommodating, but it’s difficult. There’s not enough food or space to go around, and Zhiqing’s wife especially isn’t happy about the family’s new living situation. When Zhiqing’s company suddenly closes down, he’s left with no job at all, stretching the Hu family to its limits. While it can be corny at times — featuring sappy music and characters who frequently laugh over nothing — Myriad of Lights is a solid, amazing movie. The characters are realistic and well-sketched, and the actors know how to tug at the heartstrings.

Where to watch it: Amazon has Myriad of Lights available for streaming as well. Non-Chinese speakers will have to suffer through subtitles riddled with errors and typos though.

Spring in a Small Town 小城之春 (1948)

Dir. Fei Mu 费穆

Spring in a Small Town is usually considered one of the best Chinese movies of all time, if not the outright greatest. For all its fame now, however, Spring in a Small Town was originally shunned on release by left-wing critics. Director Fei Mu had a traditionalist bent, and avoided the political themes favored by the likes of Kunlun. In 1949, when the Communists gained control of China, Fei relocated to Hong Kong, dying of a heart attack there two years later. For years, Fei and his movies were practically forgotten on the mainland, until they were rediscovered in the 1980s.

Set in 1946, not long after the end of the Second Sino-Japanese War, Spring in a Small Town follows a wealthy Chinese family in decline, the Dais. Liyan, the head of the house, is sick and depressed. He can’t afford to repair his house, which was bombed during the war, and his marriage with his wife Yuwen has soured. Life is dull and dreary for the couple, but things become more lively when a doctor named Zhang Zhichen pays them a visit from Shanghai. Zhichen is a close childhood friend of Liyan’s, but he had also dated Yuwen, back before she met her husband.

Liyan has no idea about his friend and wife’s old relationship, and while Yuwen and Zhichen begin to fall for each other again, Yuwen’s younger sister also becomes attracted to Zhichen. Granted, a movie involving a love quadrangle might have turned out ridiculous, but Fei handles the plot with grace and minimalism. The four main characters are all interesting in their own way, and you can’t help but like and sympathize with all of them. Simply put, it’s a beautifully-shot masterpiece, and even though Chinese director Tian Zhuangzhuang 田壮壮 made a great remake in 2002, few movies can compare to the original Spring in a Small Town.

Where to watch it: Spring in a Small Town is in the public domain, so you can watch it subtitled on YouTube, or download it raw on the Internet Archive.

Crows and Sparrows 乌鸦与麻雀 (1949)

Dir. Zheng Junli 郑君里

Crows and Sparrows, another movie from Kunlun, also features a cast of ordinary people struggling to get by in post-war Shanghai. Unlike its sibling Myriad of Lights, however, Crows and Sparrows is explicitly political. It depicts the Nationalists as corrupt and violent, and the criticism is so heavy that the movie wasn’t released until after the Chinese Civil War, even though it completed production earlier.

Crows and Sparrows takes place in the winter of 1948, in an apartment owned by a Nationalist official named Hou. His tenants — who derisively call him “monkey” behind his back — include a couple named Xia and their three kids, the high school teacher Mr. Hua and his wife and daughter, and an elderly man named Mr. Kong. Mr. Kong is actually the rightful owner of the apartment, but had been forced out during the Second Sino-Japanese War by Hou, a Japanese collaborator during the time.

As the Nationalist government collapses, Hou is ordered to evacuate Shanghai. He decides to sell the apartment and evacuate his tenants on short notice, sending everybody panicking to find a new place to live. The Xias hope they can buy the building by buying gold off the black market, while Mr. Hua works to move his family into his school’s dormitories, though the teachers are on strike and his Nationalist superiors suspect him of supporting them. Crows and Sparrows can get bleak at times, but it has a sense of charm and satire that other political pieces of the time lack. Whatever the obstacles, the tenants remain optimistic, and the movie ends on an upbeat Chinese New Year celebration.

Where to watch it: Crows and Sparrows was released on VHS in the United States more than two decades ago. If you (understandably) don’t feel like digging a VHS player out, the educational archive NJVID has the movie available to stream for free.

This Life of Mine 我這一輩子 (1950)

Dir. Shi Hui 石挥

The star of such hits as Long Live the Mistress 太太万岁 and The Joys and Sorrows of Middle Age 哀乐中年 (both written by novelist Eileen Chang 张爱玲), Shi Hui was one of the biggest actors in China during the ’40s and ’50s. These movies were comedies, but Shi Hui’s masterpiece is a tragedy he directed himself, This Life of Mine. Based on a novella by Lao She, Shi also played the movie’s main character, a nameless Beijing policeman who lives through the tumultuous first-half of China’s 20th century.

The movie begins with Shi’s character wandering the snowy streets of Beijing in the present day, hungry and unemployed. Sitting down to take a rest, the man remembers he sat in the very spot decades earlier, on the day he decided to become a cop. Over the years, the policeman is a kind and friendly man, but passive and powerless. Shi’s character watches the Qing Dynasty, the Republic, and the Japanese all rise and fall, but life among his family and friends never seems to get better. Only his son Haifu decides to take a stand, leaving his father all alone to fight as a Communist guerrilla.

Far from a nostalgic tour of one of China’s great cities, This Life of Mine looks at the past with honesty and weariness. In one brutal early scene, during the last days of the Qing Dynasty, a little boy is hacked to death before his father’s eyes. Later, one of the policeman’s neighbors is forced to sell her baby daughter to a brothel so she can buy medicine for her husband. Shi’s character doesn’t fare very well either — near the end of the movie, sitting in a jail cell, he breaks down and cries, wondering what he possibly did to deserve such a harsh life.

Considering the acting and directing on display in This Life of Mine, Shi Hui might someday have gone on to top it. His last days, unfortunately, weren’t much brighter than his magnum opus. Shi could be cynical and rude, and he eventually ran foul of Communist authorities. During the Anti-Rightist Movement, Shi was denounced as a reactionary. His career on the wane, and in a politically tough spot, Shi boarded a boat and killed himself by jumping overboard in December 1957.

Where to watch it: This Life of Mine is another public domain movie. The quality isn’t the best, but you can download and stream a copy with English subtitles from the Internet Archive.

Also see: