5 influential movies from the Fifth Generation of Chinese filmmakers

Coming of age during the Cultural Revolution, China’s post-Mao filmmakers would revolutionize the industry with story-driven movies utilizing vivid colors and innovative techniques.

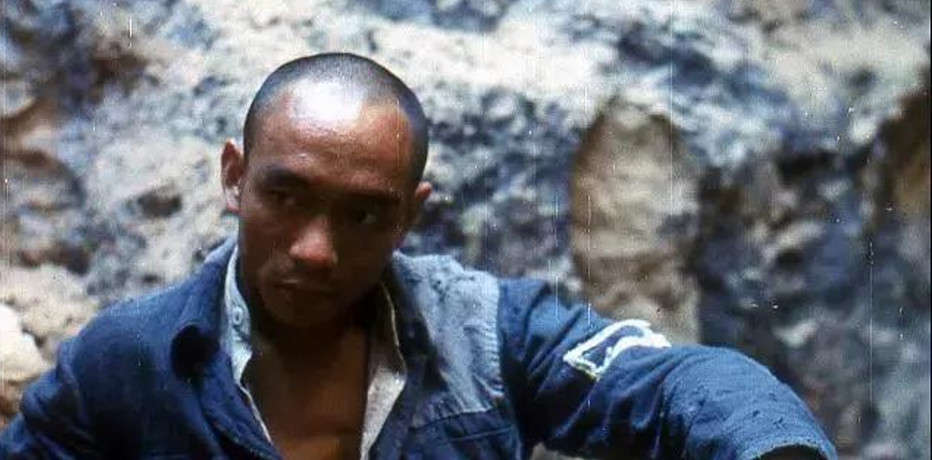

(Top images, clockwise from left corner: The Black Cannon Incident, One and Eight, The Horse Thief, Yellow Earth, Red Sorghum)

As it did to so many other fields of the country, the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) greatly disrupted the movie industry in China. Many movies were banned, and very few new ones were made. In 1978, two years after the chaos subsided, the state-run Beijing Film Academy once again opened its doors. The batch of film students who began their studies that year would graduate in 1982, counting among their classmates such famous directors as Chen Kaige and Zhang Yimou. This generation of post-Mao filmmakers would chronologically become known as the Fifth Generation, and they would revolutionize the world of Chinese movies during the 1980s.

Of course, the Fifth Generation of Chinese filmmakers aren’t exactly a unified group. Many of them were born during the 1950s, and coming of age during the Cultural Revolution. Though they came from generally privileged families, they suffered like other Chinese of the time, sharing similar experiences. After graduating, they set out to break with the propaganda-centered themes of older Communist-era movies, adding social commentary and ambiguity. Their movies were also more image-oriented, and used innovative techniques like long shots and vivid colors.

The Fifth Generation put the international spotlight on Chinese movies for the first time, and their output won numerous awards and acclaim from Western film critics and festivals. While some of these filmmakers continue to work today, the end of their heyday is generally considered to coincide with the Tiananmen Square massacre, after which the Sixth Generation of filmmakers begin to take precedence. With that in mind, this list is limited to Fifth Generation works only from the 1980s. This group has made a lot of great movies, and since it’d be difficult to cover them all in a single article, we’ll be looking at just five of the most influential from the Fifth Generation’s peak.

One and Eight 一个和八个 (1983)

Dir. Zhang Junzhao 张军钊

Zhang Junzhao, who died earlier this June, is a good candidate for the mantle of “first Fifth Generation director.” Only a year after graduating from the Beijing Film Academy, Zhang pushed his superiors at the Guangxi Film Studio to allow him to direct an adaptation of Guo Xiaochuan’s 郭小川 epic poem “One and Eight.” Along with his collaborators, the likes of He Qun 何群 and Zhang Yimou 张艺谋, Zhang Junzhao prevailed, promising the studio that they would work as mere assistants for the next decade if their pet project was unsuccessful.

Set during the Second Sino-Japanese War, One and Eight is the story of nine men who are kept as prisoners by the Communist Eighth Route Army. One is an innocent soldier accused of being a traitor, and the others are a collection of criminals, including bandits, deserters, and a spy. With a group like this, none of these guys are anybody’s idea of a patriot. When a battle erupts with Japanese forces though, the group’s courage is challenged, forcing them to fight the enemy and redeem themselves.

Upon completion, Zhang and his collaborators remained unsure how the movie would be received. Its criminal anti-heroes, and its consciously artistic style, made it very different from other Chinese war movies. While censors separately inspected the movie, Zhang and his team decided to hold a special screening at the Beijing Film Academy. To their astonishment, One and Eight brought the audience to tears. Their classmates hugged them, and their teachers congratulated them. Unfortunately, the censors weren’t as enthusiastic about their groundbreaking new work. One and Eight was delayed for release until 1987, at which point the Fifth Generation was already in full swing.

Yellow Earth 黄土地 (1984)

Dir. Chen Kaige 陈凯歌

One and Eight gets credit where credit is due, but it was really Chen Kaige’s Yellow Earth that made the Fifth Generation known, both inside and outside of China. When the movie was released in 1984, nobody had quite seen anything like it before. At first, a number of mainland critics had no idea what to make of Yellow Earth. After its screening in Hong Kong made a great buzz, selling a million tickets in the city in only six days, mainland viewers warmed up to it on its re-release. According to Australian scholar Bonnie McDougall, the success of Yellow Earth “constituted altogether such an event in Chinese film history that the Chinese film world has never been the same since.”

Taking place in the spring of 1939, Yellow Earth trails Gu Qing, a soldier who travels from the city of Yan’an in Shaanxi to a village so he can collect folk songs for the Communist Party. Gu finds the peasants here in a wretched state, plagued by poverty, superstition, and a strong belief in fate. One of the more unfortunate villagers, a teenage girl named Cuiqiao, is arranged to marry a man much older than her. Fascinated by Gu’s stories of the Communist army, Cuiqiao wants to go back with him to Yan’an, but “fate” has something else in mind for her.

With its ambiguity and strong focus on images, Yellow Earth was different from most of the other movies made in China since the Communist Party’s takeover in 1949. It was a new kind of movie, where peasants and soldiers weren’t idealized, and the audience wasn’t sold a moral lesson. Nowadays, these sort of things might be taken for granted, but they were a radical move at the time. Regardless, on its aesthetic qualities alone, Yellow Earth is a classic, and regularly tops lists of the best Chinese movies.

The Black Cannon Incident 黑炮事件 (1985)

Dir. Huang Jianxin 黄建新

In recent years, director Huang Jianxin has become known for co-directing star-studded historical epics like The Founding of a Republic 建国大业 (jiànguó dàyè) and The Founding of a Party 建党伟业 (jiàndǎng wěiyè). These movies, dealing with the history of the Chinese Communist Party, have been criticized outside of China as blatant propaganda. Looking at Huang’s earlier features, it’s a bit odd that he ended up making this kind of work. He’s traditionally had a satirical bent, and instead of making lavish period pieces like other members of the Fifth Generation, has focused on more modern, urban fare.

A better example of Huang’s ouvre is his fantastic debut, The Black Cannon Incident. This was the first satire to come out of China’s movie industry since the late 1950s, skewering the absurdities and paranoia of the Chinese bureaucracy. It follows a man named Zhao Shuxin, who works as an engineer and German interpreter at a mining company. Shuxin is a loner obsessed with Chinese chess, carrying a set of pieces wherever he goes. After coming back from a business trip, Shuxin discovers that his black cannon piece is gone. Anxious, Shuxin rushes to the post office and sends a telegram, asking the hotel he stayed at to find it.

The innocent message is completely misinterpreted by the authorities, who believe the black cannon is a weapon. While the police secretly investigate the mysterious “Black Cannon Incident,” Shuxin is replaced at his post without even knowing what he’s done wrong. For a ridiculous misunderstanding, Shuxin and his company suffer a series of misfortunes that could easily have been avoided. It’s a dark and dry comedy, and Huang would later continue the story with Dislocation 错位, a sci-fi sequel in which Shuxin creates a robot clone to do his job for him.

The Horse Thief 盗马贼 (1986)

Dir. Tian Zhuangzhuang 田壮壮

The Horse Thief is one of the most difficult — and fascinating — movies to come out of the Fifth Generation. Director Tian Zhuangzhuang has made several movies about China’s ethnic minorities, and The Horse Thief is an ethnographic study of the old Tibetan way of life, complete with Buddhist rituals and sky burials. There’s barely any dialogue, and the cast is made up of non-professional actors, giving the movie a documentary-like feel.

Set in 1923, The Horse Thief is centered on Norbu, a Tibetan man who steals and sells horses to provide for his family. Everybody in Norbu’s community knows about his stealing, and when he’s finally confronted by his clan’s elders, Norbu and his wife and son are exiled. Their lives in the harsh Tibetan mountains now get even harder, and Norbu’s son soon falls sick and dies. After his wife gives birth again, Norbu is determined to change, but finds it difficult to feed his family living an honorable life.

On its original release in China, The Horse Thief was a financial flop. While the average movie of the time typically sold 100 prints to theaters, The Horse Thief sold only seven copies. Ordinary moviegoers found it boring and confusing, and critics weren’t much impressed either, calling Tian an elitist. When questioned by the film journal Popular Cinema about the controversy, Tian went so far to shoot back that The Horse Thief was made for “audiences of the next century.”

Red Sorghum 红高粱 (1987)

Dir. Zhang Yimou 张艺谋

After working as a cinematographer on One and Eight and Yellow Earth, Zhang Yimou took the director’s chair in 1987 and adapted a novel by Mo Yan 莫言 for his directing debut, Red Sorghum. Like these two earlier movies, Red Sorghum revisits the period of the Second Sino-Japanese War, shifting the location to rural Shandong. Zhang’s movie, however, has a more nostalgic, folksy feel to it. The narrative is related by a nameless man, telling the tragic story of his grandma Jiu’er and how she came to meet his grandpa.

As a young woman, Jiu’er’s poor father forces her into an arranged marriage, exchanging his daughter for a donkey. Jiu’er’s husband Li Datou is an old leper, but he’s also the owner of a wine distillery. In a vivid opening scene, Jiu’er is carried off in a red sedan chair, held by a group of cheerful, singing men. After coming into a sorghum field, the party is ambushed by a masked bandit, and Jiu’er is nearly abducted before one of the chair bearers rescues her. The man who saves her turns into her lover, and when Li Datou inexplicably dies, Jiu’er inherits the distillery and all the problems that come along with it.

The story of Red Sorghum is evocative of an old family legend or folktale, with some of the most gorgeous images you’ll ever see on a movie screen. It was not only an important work for Zhang Yimou, now the best-known Chinese director in the world, but it also helped launch the careers of its two leads, Gong Li 巩俐 and Jiang Wen 姜文. Jiang has become an amazing director in his own right, and Li and Zhang have since collaborated on eight other movies, including the internationally-acclaimed Raise the Red Lantern 大红灯笼高高挂 and To Live 活着.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SwfJUT7YzIk

Also see:

Film Friday is The China Project’s film recommendation column. Have a recommendation? Get in touch: editors@thechinaproject.com