Chinese soccer, with its government meddling, still doesn’t get it

The China Sports Column is a The China Project weekly feature in which China Sports Insider Mark Dreyer looks at the week that was in the China sports world.

Oh to be a fly on the wall at the meeting that took place in Beijing this week between senior representatives from soccer’s world governing body FIFA and the Chinese Football Association (CFA).

The one topic that should have been top of the agenda — government interference in the sport — was almost certainly not discussed, while plenty of the usual platitudes were belched afterwards.

Croatian football legend Zvonimir Boban, who won four Serie A titles and a UEFA Champions League with AC Milan in the ’90s, while also captaining his national team to third place at the 1998 World Cup, was the point man for FIFA in his current role as Deputy Secretary General and waffled about a “cooperation framework for potential investment.” Meanwhile, China’s head delegate, Du Zhaocai 杜兆才, said he appreciated FIFA’s expertise and resources and “expects to strengthen cooperation through future exchanges.”

Gripping stuff.

China, as everyone knows, is bidding to become a global soccer powerhouse — but does anyone really still think that has a chance of happening?

I’ve previously gone on record as saying that a “best case scenario” for China’s football plan would be becoming Top 20 team, something I’ve since revised downwards to Top 30.

But based on the latest developments, it’s truly hard to see China making much dent in the Top 50 (current FIFA ranking: 76). That’s because, for all the progress made over the past five years, the recent move to separate 55 young players from their clubs and throw them into a military-style training camp is symptomatic of a governance style that could set the country back a decade or more.

More details have been leaking out about this catastrophe since it first broke last week. In the proposed schedule, players would have to fit in four 10 km runs every day, included in a total of 10 hours of training routines.

But on what planet does running a marathon every day make you a good footballer? It’s guaranteed to run these players into the ground rather than set them on the road to glory.

By setting 2050 as a target for achieving its footballing aims, China truly seemed to grasp that this had to be a long-term project. The mantra — an eminently sensible one — was to focus on the next generation of kids and wait 20 years or more until they mature. But by changing the ground rules every few months, Chinese football has dragged itself back to the dark ages, to the time when officials were focused on short-term decisions centered around winning promotion to higher government offices.

Which brings us back to government interference.

Part of China’s 2015 soccer reform plan — which was issued by the State Council — included a mandate to officially separate the CFA from the government, curious given the fact that FIFA’s statutes specifically prohibit government interference.

That separation, we were duly informed, was then carried out over the ensuing months, although multiple sources within CFA willingly admit that little has changed on the inside and that it’s crystal clear that the reporting line leads straight back to the government. As if to emphasize that point, Du Zhaocai’s dual roles on his business card are assistant director of the General Administration of Sport of China — a long-winded name for China’s sports ministry — and secretary of the CFA’s Party committee. In other words, both his titles mark him out as a government man. There’s not even any pretense to the contrary.

The CFA is in clear breach of FIFAs "Regulations on the Status and Transfer of Players" – rules also stipulate national FAs risk being banned from calling up players if they persistently break rules. Does calling up 55 players outside an international window count as persistent? pic.twitter.com/WjXOCQA8BE

— Cameron Wilson 韦侃仑 (@CameronWEF) October 9, 2018

But here’s the funny thing: FIFA does actually ban FAs for this, and does so with some regularity. Just last week, Sierra Leone was suspended from international competition due to government interference.

FIFA has reportedly said in the past that it cannot ban China because it has never received a complaint about government interference from its own football association — i.e., the government-controlled CFA. It’s a spineless argument, backed up with ludicrous logic, but this farce has been continuing for years — since long before Chinese companies started to fill FIFA’s coffers through sponsorship deals — so the most obvious culprit, money, is perhaps not the only reason for this arrangement.

FIFA has also proactively gone after FAs in the past, undermining its own argument that the CFA would need to report its own bosses, but China remains a blind spot — and no one expects FIFA to suddenly have clarity of vision.

Most fans have long since given up on the national team, but with some proclaiming the death of Chinese football in recent days, the few remaining optimists could be extremely hard to find.

Twenty-four countries outside of the U.S. have produced close to 400 athletes who have played in the NBA.

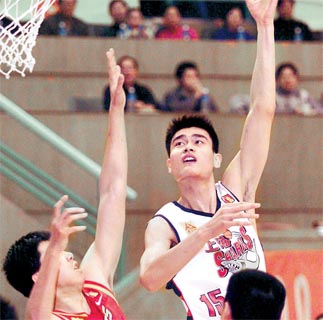

China — for all its size and love of the sport — has produced just six, and only two of those players (Yao Ming 姚明 and Yi Jianlian 易建联) logging starts in more than 10 NBA games. That’s why Ding Yanyuhang’s 丁彦雨航 debut for the Dallas Mavericks on Monday night in Shenzhen during a preseason game against the Philadelphia 76ers is more significant than his eight garbage-time minutes might suggest.

Ding missed two field goals and scored a solitary free throw at the end of the game, but was rewarded afterwards with a minor league contract that will see him play this year with the Texas Legends in the NBA’s G League.

At 6’7” — or almost a foot shorter than Yao — Ding would be the shortest Chinese player to make the NBA. But he can play: he’s won the CBA MVP award for the last two years and he’s received plenty of complimentary comments from the Mavericks camp.

Still, the road to the NBA is a long one, while for the Mavs — who signed Wang Zhizhi 王治郅 as China’s first ever NBA player, while also dressing Yi Jianlian — it’s a low risk move that allows the team to maintain their Chinese connection.

China’s cricket team has been humbled by Nepal, Singapore, Thailand, Bhutan, and Myanmar in a recent qualifying tournament, with one-sided games comparable — for American readers — to the Yankees’ recent 16-1 loss at home to the Red Sox.

In the Twenty20 version of the game, a decent score would be something over 150, with Australia once scoring 263 off their allotted 120 balls. China, meanwhile, failed to hit 50 in any of their five matches.

After after perhaps the most humiliating loss — scoring just 26 against Nepal — a Nepalese official summed up the mood: “China might be stronger in terms of power and economy than Nepal, but beating China is not a big achievement for Nepal.”

~

Finally this week, a U.S. Congressional Panel has demanded that the International Olympic Committee (IOC) strip the 2022 Winter Olympics from Beijing due to ongoing human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

Senator Marco Rubio and representative Chris Smith, who lead the Congressional Executive Commission on China, say the IOC should reassign the hosting rights for 2022, although the chances of this happening are about as slim as the Beijing area actually having any natural snowfall that year.

Smith said it was “unconscionable” that an Olympic Games could be held in Beijing under the current regime, but there would have to be an unprecedented change of heart for the IOC to take this demand seriously, especially given the fact that Beijing was awarded the 2008 Games despite widespread international opposition.

The China Sports Column runs every Friday on The China Project. Follow Mark Dreyer @DreyerChina.