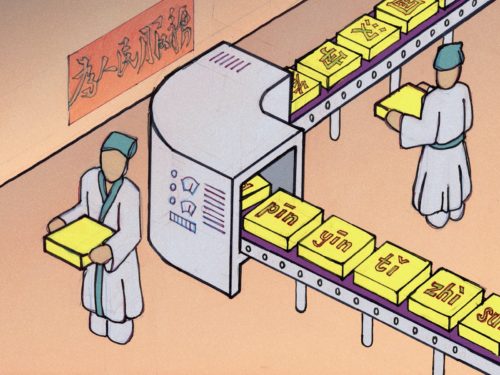

Mingbai: Explaining Chinese idioms and the stories behind them

Mingbai (明白, meaning “understand”), written by Christian Føhrby (who contributed the above illustration) and Deng Jie, is a newsletter that drops knowledge on things “everyone in China knows, but almost nobody outside the country knows.” Sign up for it at GetMingbai.com.

Mingbai (明白, meaning “understand”), written by Christian Føhrby (who contributed the above illustration) and Deng Jie, is a newsletter that drops knowledge on things “everyone in China knows, but almost nobody outside the country knows.” Sign up for it at GetMingbai.com.

Today’s column marks the return of Mingbai to The China Project. It’ll appear in this space on the final Wednesday of each month moving forward.

Like any language, Chinese is full of colorful figures of speech. Some have pretty easily identifiable counterparts in English, like “to kill two birds with one stone” (“one arrow,” in the Chinese version: 一箭双雕 yī jiàn shuāng diāo). Or at least similar meanings: in English, “to throw pearls before swine” is to waste something good on someone who doesn’t appreciate it; in Chinese, that would be like “playing the lute for a cow” (对牛弹琴 duì niú tán qín). Same same, really.

But some Chinese idioms rely on unique stories that explain their initially cryptic-sounding forms. For example, why would you not try to use an axe outside the home of a guy named Ban? Why should you never add feet to your otherwise perfectly good drawing of a snake? Read the explanations of these commonly used phrases and find out:

班门弄斧 (bān mén nòng fŭ), literally “using an axe outside Ban’s door,” is used to remind people not to overestimate their own abilities.

Master Lŭ Bān was an expert craftsman in ancient times, and everyone knew he was the best.

One day, a young carpenter came along, flaunting his hatchet and telling everyone how great he was at building things. A passerby with a sense of humor asked if the young carpenter could make a nice, wooden door like “that one,” indicating Lu Ban’s door. The carpenter was cocky — until he heard whose door it was, at which point his face turned red and he suddenly had important business elsewhere…

The phrase can be used to show respect to someone, like “me doing X in front of you would be like using an axe outside Ban’s door” (so, like, don’t mind me, OK?).

画蛇添足 (huà shé tiān zú), “drawing a snake and adding feet,” is another useful idiom that warns against adding unnecessary frills to something that’s already complete.

You know what it’s like. There’s only one cup of booze left. Everyone wants it. What do you do? You hold a snake-drawing competition (of course?), and the first to finish gets the prize!

However, when this happened in ancient China (we’re told it did), the first person to finish his snake looked at it and thought, “Ha, the others are still at it, while I have time to spare! I’ll draw four feet on my snake just to show off!”

However, when the referee (there must have been one) reviewed the snakes, he awarded the prize to someone else. The reason? Well, snakes don’t have legs, silly!

Duh.

The moral is clear: Don’t overdo it.

自相矛盾 (zì xiāng máo dùn), or, roughly, “the spear against the shield,” is used to describe things that are self-contradictory.

Once upon a time, a cocky weapons salesman stood in the marketplace and advertised his goods: “My spear is the sharpest in the world,” he shouted proudly, loudly, and salesman-like, “and it can pierce through anything!”

People stopped to listen as he continued: “And my shield is the strongest in the world — nothing can break it!”

All this obviously sounded quite good, and people were excited about these treasures, until one little boy remarked: “So — what if you use your spear against your shield?”

Ouch.

So whenever people claim two things that can’t be true at the same time, or if they just act paradoxically, you can gently inform them that you’re in a spear-and-shield situation.

塞翁失马 (sài wēng shī mǎ) or, “the old man lost his horse,” is a phrase that reminds people to not draw hasty conclusions.

An old man once discovered his horse had disappeared. His relatives thought he’d be distressed, so they came over and tried to make him feel better. But the old man wasn’t actually too worried. “Maybe this isn’t a bad thing,” he said.

The relatives didn’t really get it, but indeed, the horse soon came back, bringing another horse with it home! The relatives loudly congratulated the old man. But he wasn’t excited. “Maybe this isn’t as good as it seems,” he said.

Again, the relatives thought he was crazy. The next day, however, the old man’s son broke his leg while riding the new horse. “Poor kid,” the relatives all said, but the old man thought it might be for the better.

And boom, war breaks out, and while all other families send their young men to die in battle, the son can’t go because of his leg.

Basically, there’s no point in drawing hasty conclusions. And if people do, tell them about the old man who lost his horse and set them straight.

Come back next month for more Mingbai, and remember to sign up for the biweekly newsletter.