Who really killed Pamela Werner? Reexamining Old Beijing’s most infamous murder

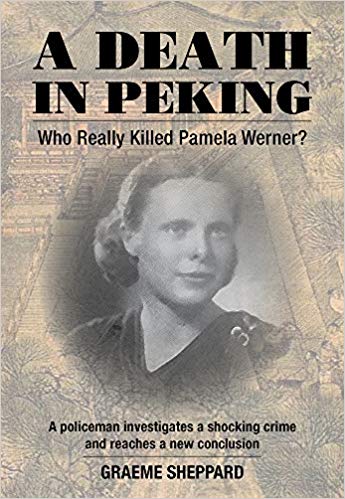

Graeme Sheppard is author of A Death in Peking: Who Really Killed Pamela Werner? (Earnshaw Books).

As a police officer it can be difficult to switch off from work. You can’t stop seeing the world through police eyes. And that was very much the case when I was lent a book to read some years ago: Midnight in Peking by Paul French. The subject was the brutal unsolved murder of Pamela Werner, a young British woman in Beijing (then known as Beiping 北平, which foreigners called Peking) in the winter of 1937.

Pamela left a skating rink on her bicycle in the dark, alone. She never made it home. Her body was found the next morning in a shallow ditch under the shadow of the city-wall. She had been mutilated beyond recognition and, most mysteriously, her heart had been stolen.

The crime terrified the community of foreigners living in Peking, but despite extensive police investigations and a number of suspects, the case remained open, with no one charged or publicly identified by the police. Midnight in Peking, however, named the guilty as several local residents — an American dentist, a former U.S. Marine, and an Italian embassy doctor — based on the archived investigative letters of the victim’s elderly father, retired British consul and sinologist, E.T.C. Werner. The book was a bestseller.

But I wasn’t convinced. From a policing perspective, the evidence simply didn’t add up. I could not conceive how the British and Chinese police had somehow failed with suspects where the father claimed to have succeeded. The police had access to none of the latest aids to policing: no DNA, no CCTV, no offender profiling, no internet-use monitoring, no mobile phone or credit card tracking. Yet neither had the father. The officers would have been working solely with the basics of evidence-gathering: secure witnesses, seize exhibits, divine real intelligence from mere rumor; methods as valid today as they were then. Yet no one was charged. What, I wondered, had really happened back in 1937? Where had the police investigation taken them?

Intrigued, I visited the UK National Archives in London and examined the father’s letters for myself — some 160 typed pages addressed to the Foreign Office in the late 1930s. And I found that the letters were full of wild and unsubstantiated allegations (many of which did not appear in Midnight in Peking). For example: collusion between police and murderers; the labeling of all manner of people as sexual deviants; the involvement in the murder of three doctors and their use of an ambulance; the body taken to a hospital for the purpose of dissection — to mention just a few. Tellingly, Werner had also paid private agents to supply him with information. Encouraged by money, there can be little doubt that they were simply supplying materials to match his preconceived ideas.

Intrigued, I visited the UK National Archives in London and examined the father’s letters for myself — some 160 typed pages addressed to the Foreign Office in the late 1930s. And I found that the letters were full of wild and unsubstantiated allegations (many of which did not appear in Midnight in Peking). For example: collusion between police and murderers; the labeling of all manner of people as sexual deviants; the involvement in the murder of three doctors and their use of an ambulance; the body taken to a hospital for the purpose of dissection — to mention just a few. Tellingly, Werner had also paid private agents to supply him with information. Encouraged by money, there can be little doubt that they were simply supplying materials to match his preconceived ideas.

Midnight in Peking’s core error, in my view, was to rely upon the crime theories of Werner, a man who was far from objective, and who possessed a bizarre personality: “a morbidly suspicious temperament,” “invariably right,” “manically quarrelsome,” and “completely mad” were just some the words used to describe him by contemporaries, people who knew him well. In all, Midnight made for a good story, but from a police perspective, it did not reflect reality or meet the requirements for its conclusion.

I started to search further, and soon found that the U.K. National Archives alone held more on the crime than had so far been revealed, including an additional British suspect.

By this stage I was hooked on the case and I spent the next several years searching for evidence from archives across the world — from the USA to Australia, from China to Italy, from Canada to Singapore: letters about the murder between diplomats; notes and memoirs; articles in newspapers; military personnel records; church missionary documents; secret reports of espionage and political assassination. I even managed to find and speak with people Pamela had lived with just before her death — children she had shared a home with. There was so much more to the crime than had ever been made public.

I also found the list of suspects growing: doctors, journalists, diplomats, soldiers. And then another discovery: there in Peking’s shadows, bringing his own influence on the case, perhaps almost inevitably, was the enigmatic and controversial figure of Sir Edmund Backhouse — one of the greatest enigmas of the 20th century.

As to identifying the offender, it was an odd combination of the contributions of Backhouse and British Chief Inspector Richard Dennis that pointed the way for me; it transpired that Pamela’s murderer was no stranger to her, but, on the balance of probabilities, was a young Chinese friend, one who formed a close part of her adolescent past. The circumstances matched the wall crime scene. They also went a long way in explaining police actions at the time. Determined though he was to solve his daughter’s murder, E.T.C. Werner’s theories were wide of the mark.

Having gathered such a wealth of evidence, I then felt compelled to write of the affair, to pen an evidence-based account of what occurred. Midnight brought Pamela’s death to the attention of the world, and for that I am grateful to Paul French. A Death in Peking provided me with an opportunity to use my police experience to not only reveal the facts behind the 1937 crime, but also to illustrate the extraordinary lives of the people involved — both foreign and Chinese — living in a period of China’s history with which many today will be unfamiliar: a turbulent time of city walls and foreign enclaves, warlords and Japanese invaders.