Jin Yong, China’s late great novelist, was a world-creator who shaped Chinese imagination

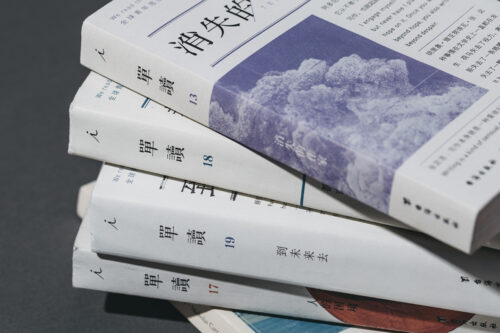

Clockwise from top left: The Deer and the Cauldron; Book and Sword; Gratitude and Revenge; The Return of the Condor Heroes; The Smiling, Proud Wanderer

Jin Yong’s passing, even at age 94, sent shockwaves of grief through Chinese-speaking populations across the world. Though many people in the West, even so-called fans of the wuxia genre — i.e., Chinese martial arts — may not be familiar with his name, every Chinese martial arts epic you’ve enjoyed likely bears Jin Yong’s influence.

Fans of the genre will likely categorize Jin Yong’s work as action-adventure with Asian characteristics, featuring Chinese historical references, philosophical themes, and hard-to-pronounce names, tied together by epic, gravity-defying battles. But while martial arts fights are always featured prominently, the action merely serves as brush strokes with which to paint a vivid, colorful world full of wonder.

If you’re not a fan of the wuxia genre, on the other hand, you might be feeling a bit lost. Why has Jin Yong’s works been called a “shared language” among all ethnic Chinese groups?

Consider this your wuxia primer. First, let’s take a closer look at jianghu 江湖 and xia 侠, the central concepts of the genre:

Jianghu translates literally as “rivers and lakes,” and is a philosophical term conceived during the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC), referring to the expansiveness of the world. Today, jianghu refers to the uncharted territory beyond or beneath lawful society, both in fiction and in real life. This dangerous and unpredictable world is comparable to the American Wild West, the world inhabited by Italian mafia, and Batman’s Gotham. A popular saying goes, “When in jianghu, our bodies are not our own.” In the cutthroat world of jianghu, all are compelled to abide by its strict rules and ethics if they want to survive; conversely, the code of conduct from the lawful world carries little weight here.

Xia has no direct translation, but broadly equates to heroes with subversive tendencies. They are defined by their pursuit for justice in unorthodox ways, often as vigilantes that cannot suffer the corruption or ineffectiveness of institutions. They are very much “Chaotic Good” from the Dungeons & Dragons alignment system, the combination of a good heart and free spirit. Xia is almost always a wuxia — a hero skilled in martial arts — because her deadly skills allows her to be an anti-establishment agent who defies and resists the status quo. These heroes are typically driven by a deep sense of purpose and righteousness guided by strong values and strict codes of conduct; think Luke Cage or Han Solo, rule-breakers with a credo.

To those who find the Chinese wuxia genre culturally inaccessible, it may surprise you to learn that it bears striking similarities to the modern superhero genre, which explores what the world would be like if good and evil are embodied by extraordinary people with the capability to shape the world according to their vision. This is why Jin Yong counts the likes of Deng Xiaoping and Jack Ma among his superfans, themselves powerful individuals who have shaped China through their actions.

When I was growing up in New Jersey, I was fed a steady diet of American superhero cartoons such as Batman, Spiderman, and X-Men, but during my summers in Beijing, I always switched to Jin Yong martial arts TV shows for the same fix.

I used to park myself on the couch next to my stoic grandfather in front of the TV, and we’d bond over the latest adaptation of one of Jin’s epic novels. I was spellbound by the larger-than-life characters whose exquisite skills bordered on supernatural, the high stakes struggle between good and evil, and the grand operatic romances.

My retired civil servant grandmother disapproved: she thought Jin Yong’s stories glamorized violence and indecency, and urged me to watch something more respectable like the historical biopic of great Qing Dynasty emperors.

The funny thing was, those historical biopics featured every bit as much violence and indecency as the Jin Yong shows; what set them apart was that the former was firmly rooted in reality, while the latter existed in a heightened, romantic version of the same reality known as jianghu. Therein lies the core appeal of Jin Yong’s novels: they celebrate familiar Chinese values while lifting the readers out of the grind of everyday life.

Relatable fantasy

The summer when I was 15, plagued by uncertainty about the future, identity issues, and hopeless crushes, Jin Yong’s The Smiling, Proud Wanderer 笑傲江湖 (xiào ào jiānghú) was the perfect antidote for my growing pains. I received the novel as a gift, and devoured it behind my strict grandmother’s back. I discovered a cut-throat world of jianghu populated by opportunists, loners, rebels, sycophants, and innocents as various clans struggled for dominance, alliances were forged and broken, love blossomed and died…in short, a perfect metaphor for high school.

The thing that captured me most was the enormous agency afforded by the players; jianghu was essentially a meritocratic realm where possession of the right skills afforded you the power to single-handed push back against enormous institutions and alter destiny. It wasn’t always that the powerful characters had godly abilities to do as they please, but the most tenacious heroes always seemed to have a fighting chance.

To a teenager feeling trapped by her life, and constantly insecure about her capabilities, this pulp fiction novel pumped me up with much-needed optimism to keep going. What’s more, it also offered an important lesson in the value of forging my own path: Linghu Chong 令狐沖, the central protagonist of The Smiling, Proud Wanderer, discovered through trials and tribulation that abandoning established fighting styles and embracing true improvisation can render one unbeatable in combat.

Subversive tradition

The themes that reminded me of high school also served as a political allegory for power struggles amongst factions. This is why some of Jin Yong’s novels were banned by the Chinese government in the 1970s, as they satirized the Cultural Revolution, though the official explanation for the ban was that his books promoted feudal values that went against contemporary communist ideals.

The Chinese Communist Party’s ban on Jin Yong drew on the wuxia genre’s less-than-reputable place within the Chinese literary tradition as an embodiment of indecent values and tawdry low culture. But exactly because wuxia literature celebrates the fringe rather than centralized power, it is the perfect vehicle for examining the corruption and inefficacy of the establishment.

Much like the American Western, jianghu is a realm with swift and sometimes draconian justice. Wuxia heroes often have no choice but to take justice in their own hands, and most importantly serve as a check on corruption in the government and systems that are meant to serve rather than exploit the people. Today, these themes remain more relevant than ever as more wuxia works continue to be produced, building on Jin Yong’s enduring legacy.

But just as J. R. R. Tolkien is hailed as the king of Western high fantasy, Jin Yong too is often imitated but never duplicated. It remains to be seen if another will ever dazzle us the way Jin Yong did. Or perhaps he will go down in history like one of his unforgettable heroes, a true one-of-a-kind wonder.

Also see:

https://thechinaproject.com/2018/11/02/friday-song-the-songs-dreams-and-worlds-inspired-by-jin-yong/