The Red Runners of Peking University

“The earth belongs to us, the workers, no room here for the shirk, how many on our flesh have fattened!” So sang 20 students standing in a circle on a dark volleyball court. Peking University (PKU) is no stranger to “The Internationale”; 3,000 of its students sang the socialist anthem on their way to Tiananmen, one fateful day almost three decades ago.

Since the end of October, the Peking University Marxist Student Association (PKUSMA) has been organizing nightly runs around the May Fourth running track. The drill is always the same: Every self-introduction must be followed by the cry: “The freezing winter cold can be melted by our boiling blood!” Older students proudly shout at the top of their lungs, while newcomers only pluck up the courage after some encouragement.

This is a show of force, not an excuse to exercise. Five laps, run in a double column, one of the senior members keeping the pace at the flank with a militant “hip-hup” while the flagbearer, usually the tallest in the group, runs at the head, holding high a red flag with “Peking University Marxist Student Association” sewn in golden characters on it.

At every half-lap they let out a shrill chant that echoes far and wide, startling nearby joggers; “Look out for the workers and peasants, achieve far-reaching reform!” the group cries out in the first lap, drawing a crowd to the sidelines, who quietly observe the procession.

After only the second lap, fatigue starts to take a toll on discipline. The pudgy pace-keeper now catches a few breaths every “hip-hup” while those at the back of the group struggle to keep up with those following the flagbearer, grimacing as his lanky physique struggles to keep the flag erect.

Then, a group of energetic People’s Liberation Army cadets start running in nigh-perfect synchronization on the inside lane, cruising past the breathless students. The spectacle draws laughter from the crowd, many sneering as they take pictures of the group that had looked so intimidating moments ago.

Some of the newcomers in the Marxist society group start to feel insecure, asking the pacekeeper what all the staring is about. He huffs and puffs for a few seconds before replying drily, “Who cares?” Once the five laps are over, they hurry toward a volleyball court on the far side of the running track, where they will continue to espouse their love for Marxism away from the public gaze.

The timing of these morale-boosting runs is no coincidence. Marxist student associations at China’s most prestigious universities have been subject to increasing repression ever since around 50 of their members went to Huizhou this summer to support the unionizing efforts of workers at the welding machinery firm Jasic Technology. This year, PKUSMA was not allowed to register as an official club; Renmin University has blackmailed students involved in the Jasic worker protests; and Marxist students at Nanjing University were assaulted after carrying out on-campus protests against the university’s refusal to register the Marxist society as a club.

Despite their small numbers, these students pose a new challenge to the Party-state. Marxist ideology was supposed to be a safeguard against the Western ideas that had driven Peking University’s Tiananmen protesters. Instead, Marxism has become a catalyst for, in the words of the Renmin University Communist Party branch, “defection” (叛 pàn) — anathema to the Party’s obsession with cultivating citizens who value the CCP-maintained status quo above all else, including moral solidarity.

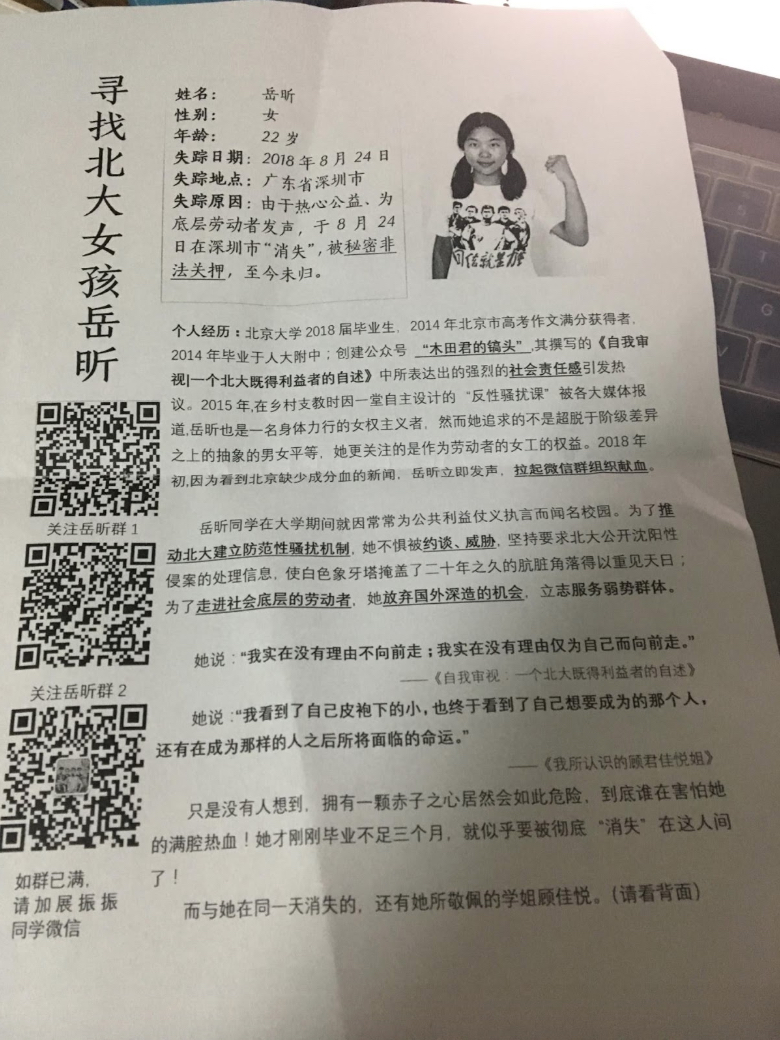

Perhaps the most public figure associated with the protests is PKUSMA’s Yuè Xīn 岳昕. In April this year, she wrote an open letter to Peking University (PKU) authorities demanding full disclosure of an investigation into a sexual harassment and suicide case dating back to the 1990s. PKU’s top brass harassed and tried to censor Yue, before coming to a face-saving compromise by allowing her back to school.

But after graduating, Yue ran off to Huizhou, Guangdong Province, where she became a lead organizer of workers’ protests at Jasic Technology, a Shenzhen-based car parts company whose workers allege abusive treatment. Yue maintained an active presence on Twitter and gave interviews to Western media outlets such as Reuters.

Yue has now been missing for over 70 days. She was last seen in a Shenzhen police station on August 24. Now no one, including her parents, knows where she is.

“Yue is most likely being kept isolated somewhere remote, without any access to the internet,” one her associates, Wang Xiaoming (a pseudonym), told The China Project. Wang participated in the Jasic workers’ protests alongside Yue, and in August, was one of 40 students snatched by Shenzhen policemen and placed under detention.

“They had three guards watching me in an empty classroom 24/7,” recalls Wang. “I was detained for three days without a phone or any contact with the outside world.”

Wang had to wait 20 days before the police returned his phone. He had to go the a police station in his hometown to get it. When he got there, he found a government official and his PKU Marxism lecturer waiting for him. They invited him to an empty room to “exchange views,” which was code for a lecture on how stability was the most important objective of Chinese Marxism.

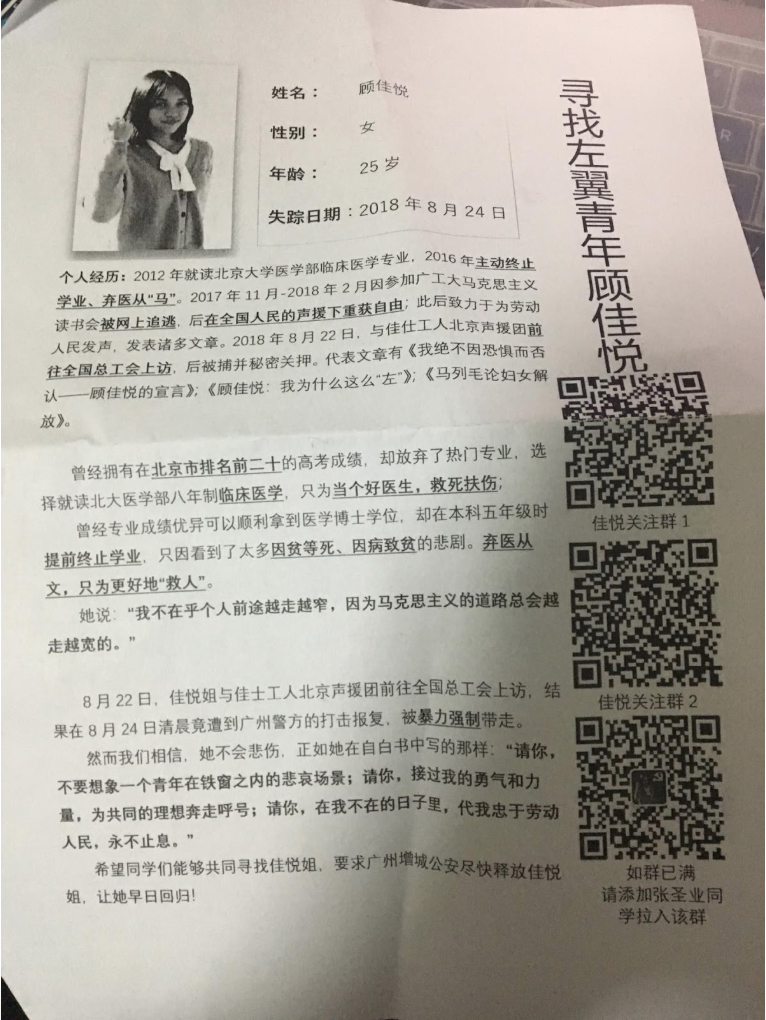

This had no effect on Wang’s drive to find justice for his kidnapped classmates. After returning to PKU, he helped found Look for the Moon (寻月小组 xún yuè xiǎozǔ), a PKU student group that aims to raise awareness on Yue’s disappearance, as well as that of Gù Jiāyuè 顾佳悦, a PKU medicine graduate who was reportedly kidnapped from her home in Beijing on the same day Yue was taken away by policeman. The group’s name is a reference to the student activists’ names: Both have the sound “yue” in their names, a homophone of yuè 月, which means “moon.”

Like Yue, Gu was a selfless activist and an avowed Marxist, known by her friends for buying medicine and other basic necessities to give to members of the 10,000-strong army of migrant workers who clean, cook, and provide low-cost campus security at PKU. Gu came under the radar of the Guangdong provincial government as a member of the “Eight Young Leftists” — a reading group on working-class activism based at the Guangdong University of Technology.

Wang Xiaoming and his classmates have caused quite a stir over the past few weeks. In early November, police were called in twice after they distributed flyers in the university canteens. Rather than complying, the group refused to exit the premises, repeatedly declaring the legality of their actions as they filmed the police’s every move. This lack of deference toward authority, rarely seen on Chinese campuses, is perhaps why Yue Xin has been treated so harshly.

“Even though doing this might get me in trouble, I don’t think it’s right to always put our careers in front of everything,” said Lǐ Huī 李辉, a medicine undergraduate who participated in the flyer distribution.

Li was inspired to take action by Gu Jiayue, her senior. Gu’s inspiring sayings — such as “As my activism increasingly narrows my career path, the path of Marxism becomes increasingly wider” — along with passages pulled from dozens of essays on social activism from Yue Xin’s blog were printed on the flyers that Look for the Moon members distributed around PKU. Multiple QR codes to WeChat groups on the issue, as well as the URL for a WordPress blog and a Gmail address, were also added.

Many of those who participated in the distribution of the flyers also participate in the nightly runs of the Marxist society. Although Wang Xiaoming is an avowed Marxist, he states that Look for the Moon has no formal links to the Marxist association, its sole aim being to work toward the safe return of Yue and Gu rather than promote the ideology espoused by the two.

“If people inside the WeChat group want to talk about the Jasic protests, we won’t stop them,” said Wang, who spends most of his days trying to keep the Look for the Moon WeChat groups from getting shut down. This also involves kicking out any student who criticizes the group’s campaigning. Minutes after Look for the Moon began distributing flyers, PKU’s university forum was filled with threads from students who accused Wang of operating out of a “desire to become a martyr.”

“Although some students have tried to demonize us, most of PKU’s students have expressed their solidarity and support,” said Wang.

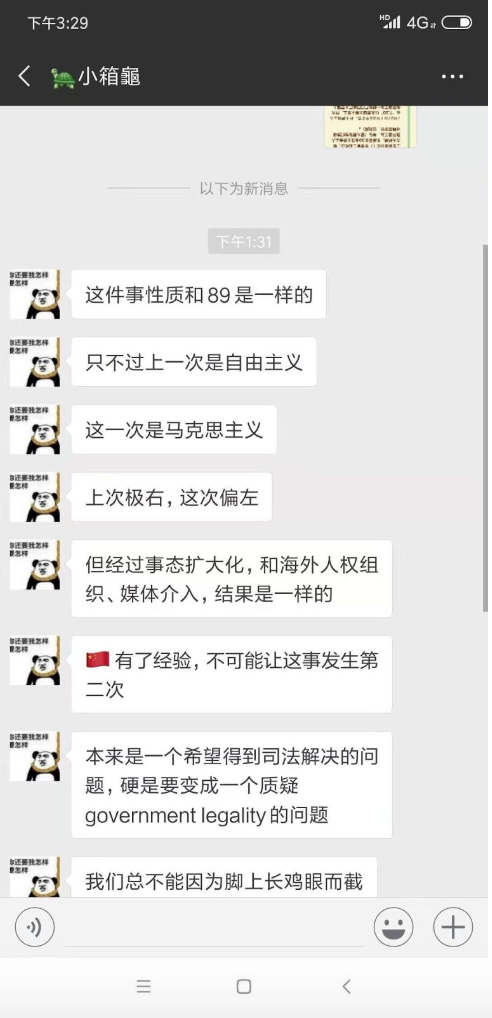

PKU has long been known for being the only university in China where critical stances toward the government and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) could be expressed relatively freely. But PKU’s current political climate is much more conservative than in the past. As the moderator of the Look for the Moon WeChat groups, Wang also has to warn group members to avoid straying away from the question of how to find Yue and Gu. They have difficulties trying to discuss “sensitive” subjects like the differences between classical Marxism and Maoism, the events of 1989, and the CCP’s methods of dealing with political opposition.

One PKU student described the group’s activities as a challenge to the Chinese government’s legality and thus akin to the 1989 Tiananmen protests.

“Apologies to all the group members, but the link we just sent is no longer working; the essay got deleted within minutes of publishing” was the notice Wang had to post shortly afterward.

Wang now encourages the group to use the encrypted messaging service Telegram as a safer form of communication for those interested in debate. But not even Telegram is safe — PKU administrators appeared in a virtual meeting organized by the group on Telegram during the first week of November.

On October 23, the Ministry of Education announced (in Chinese) that Qiū Shuǐpíng 邱水平 was appointed as Party secretary of PKU, a vice-minister-level position in the Party hierarchy. Qiu’s predecessor was demoted to president of the university: As with all organizations in China, the Party secretary is the person with the power. Qiu is a career politician with a background in law and policing. From 2013 to 2014, Qiu was Party secretary of the Beijing branch of the Ministry of State Security, China’s intelligence and counterintelligence agency, which also handles domestic threats to the Party’s rule (see his résumé, in Chinese).

Since Qiu’s arrival, all signs of student activism have been met with immediate responses from authorities. And ever since Look for the Moon distributed flyers around the campus, a pair of security guards have been standing outside the canteen entrance, watching the students walking in and out.

Last Friday, November 9, two Peking University graduates involved in the Jasic workers’ protests were kidnapped late at night by 10 unidentified men outside a PKU canteen. Students who witnessed the scene reported being beaten and forced to delete the footage they had recorded on their phones. In tandem, the Look for the Moon WeChat groups were all shut down in one fell sweep. Nevertheless, Wang and others have hastened to create a new set of groups, this time called PKU Alumni Search Group (寻找校友群 xúnzhǎo xiàoyǒu qún).

One of the witnesses, Yú Tiānfū 于天夫, has been reported missing after posting essays and videos on social media describing the events of that night. Classmates suspect he has been forced to return home without a phone, a treatment similar to the one meted out against Wang this summer.

“[Qiu Shuiping] may want to shut us up, but what matters is whether he is able to outsmart us,” said the flagbearer of the nightly runs, a second-year medicine undergraduate.

“When I started to think about the question of an ideal society last year, Marxism was the only valid answer,” added the flagbearer, who wished to remain anonymous.

“Why can’t the proletariat become the dominant class? It can be done,” Wang stated matter-of-factly. After Friday’s crackdown, students involved in Look for the Moon activities worry that Wang is next in line.

Although Wang declined to share his opinion on Chinese politics, his espousal of Marxism stems from a lifelong concern with improving the conditions of the Chinese working class. His father, a construction worker, died in an accident when Wang was still a child while his mother is now working in a textile factory in Shanghai.

After arriving at PKU in 2013, Wang quickly found the student Marxist association. That year, the association had produced a report on the condition of PKU’s rural migrant workers, which inspired Wang to publish his own version of the report in May this year.

The 23-year-old does not see any contradiction between Look for the Moon campaigning and his own career prospects in China. Working for the government, a trade union, or an NGO are all possibilities in Wang’s eyes, as he believes these organizations will look well upon his track record of social activism, even if this is tainted by a criminal record for having been arrested this summer.

“I think the reason behind Yue and Gu’s kidnapping is corruption within the Guangzhou local government,” observed Wang, who believes the Look for the Moon campaign will push central authorities in Beijing to punish those responsible for the kidnappings.

“Wherever Yue and Gu are, that’s where I will be,” Wang declared. “Wherever they stand, that’s where my brightest prospects lie.”

At the time of publishing, Yue and Gu are still missing.