Hanshan: Investigating the life of Chinese literature’s most mysterious poet

The poet Hanshan 寒山, a name meaning “Cold Mountain,” ranks as one of the most eccentric and mysterious figures of Chinese literature. He is said to have lived during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), dwelling in a cave or hut in Tiantai Mountain near modern-day Taizhou, Zhejiang. In Chinese and Japanese art, he is often depicted as dirty and raggedy, smiling mischievously with his friend Shide 拾得. His poetry, written in a direct, colloquial style, was satirical and spiritual, touching on both Buddhist and Daoist themes. Hanshan also wrote poems about his own life, but his real identity is completely unknown. His name, in fact, is a pseudonym that refers to a place in Tiantai Mountain.

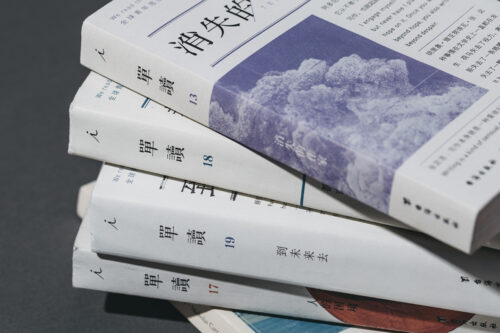

With no real name to pin the poems to, some scholars have suggested that Hanshan’s work was actually written by a collective of different people; others speculate that the legendary poet never even existed. The collection of 300 poems attributed to Hanshan is known as the Hanshanzi 寒山诗. It isn’t exactly clear when these poems were written, or when they began to become popular. There are references to Hanshan in other works during the 9th century, while the earliest surviving copy of his poems dates back to the 12th century. Editions of the Hanshanzi usually include a preface written by Lu Jiuyin 闾丘胤, a contemporary official who supposedly met Hanshan and collected his work.

In his preface (translated by Wu Chi-Yu 吳其昱 in an article here), Lu says that “nobody knows where Han-shan came from.” He would go to Tiantai Mountain’s Guoqing Temple to get food, laughing and talking to himself for hours in one of the temple’s corridors. One of the monks who worked in the kitchen, Shide, befriended him and provided his food. Lu first heard of Hanshan from Fenggan 丰干, another monk associated with the poet and Guoqing Temple. Fenggan unexpectedly showed up at Lu’s house one day, before he was about to leave to take up a new post in the region. Lu was sick with a headache, but Fenggan healed the official’s head by simply sprinkling water on him. Fenggan told Lu of Hanshan and Shide, claiming that they were incarnations of bodhisattvas who could be found at Guoqing Temple.

After arriving at his new post as prefect of Taizhou, Lu paid a visit to Guoqing Temple three days later. He asked the monks there about Fenggan, Hanshan, and Shide. He learned that Fenggan no longer lived at the temple, and his living area was now inhabited by a tiger. Hanshan and Shide were in the kitchen at the time, and when Lu went to see them, they burst out laughing at him. Lu tried paying homage by bowing, but the two recluses only continued laughing and shouting, until they left the temple hand-in-hand.

Later, Lu arranged to give them clothes and medicine, sending messengers to Hanshan. The poet cried out, “Thieves! Thieves!” when he spotted the delivery men, and retreated into a cave that immediately sealed itself up. Shide vanished too, and nobody apparently saw either of the men ever again. Lu requested that a monk collect what they left behind, finding Hanshan’s poems scattered on bamboo, trees, and walls. The result of this effort was the Hanshanzi. In his closing remark, Lu notes, “I, who am devoted to Buddhism, am very happy to have met them.”

Aside from the various legends surrounding Hanshan, Lu’s preface was once commonly accepted as a source for the poet’s life. Since the 1920s, the text’s authenticity has increasingly come under scrutiny. The prefect Lu Jiuyin, it seems, doesn’t seem any more real than Hanshan.

Despite Lu’s claim to be an official, his writing style is so unrefined and repetitive that the scholar Robert Borgen has remarked that “a man with so clumsy a prose style could not have passed his civil service examinations, much less risen to such a high position in Tang officialdom.” To make matters sketchier, while there are records of a Lu Jiuyin living during the Tang, this particular man served as prefect of Lichou rather than Taizhou.

Even though it’s been difficult to pick out an author for the Hanshanzi, that doesn’t mean some sleuths haven’t tried. The academic Wu Chi-Yu even came up with an exact name: a 7th-century Buddhist monk named Zhiyan 智俨. In an old biography about his life, it is said that Zhiyan was originally a soldier, but gave up the military life to become a monk. In his 40s, he left his family and went to live in the mountains. At one point, some of his army friends visited Zhiyan and made an unsuccessful plea for him to return to a normal life. Interestingly, one of these men was a governor named Lu Jiuyin.

The problem with this theory, however, is that Zhiyan was never known to have written poetry. The preface of the Hanshanzi also mentions that the author was previously unfamiliar with Hanshan. On the other side of the debate, some have argued that Hanshan’s poetry was written by multiple people. Based on an analysis of the poems’ rhyming combinations, E.G. Pulleyblank proposed that the collection could be divided into two different groups: the livelier “Han-shan I,” written in the early Tang period, and the more didactic “Han-shan II,” which was written later, possibly by Buddhist admirers. According to this, the original Hanshan must have composed his poems between the late Sui and early Tang Dynasties, while the other authors added their pieces later in the Tang.

Of course, perhaps the best account of Hanshan’s life might come from his own work. Translator Burton Watson, writing in the introduction of his translation Cold Mountain: 100 Poems by the T’ang poet Han-Shan, believed that most of the poems were probably written by “a gentleman farmer, troubled by poverty and family discord, who, after extensive wandering and perhaps a career as a minor official, retired to a place called Cold Mountain among the T’ien-t’ai range.”

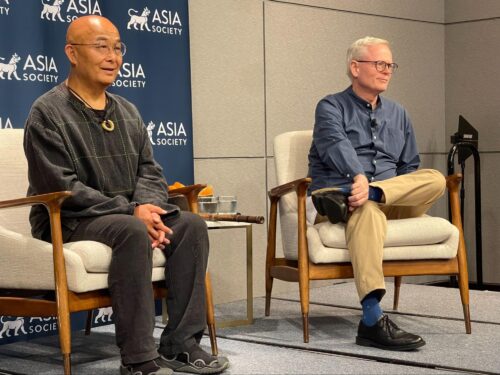

Whoever Hanshan might have been, his poetry has inspired countless artists, Buddhists, and countercultural figures. Japanese writers like Matsuo Bashō have greatly admired Hanshan, while American beatniks and hippies championed Hanshan as a fellow free spirit, with Jack Kerouac even dedicating his novel The Dharma Bums to the poet. When it comes to reading Hanshan in English translation, there are also plenty of options. Kerouac’s friend Gary Snyder introduced Hanshan to many American readers with his RipRap and Cold Mountain Poems, and notable scholars like Arthur Waley and Burton Watson have produced selected translations as well. By far, American author Red Pine’s The Collected Songs of Red Mountain is one of the most extensive, including both the original Chinese text and his own English translations of the poems.