Love in Rural China: A matter of trying

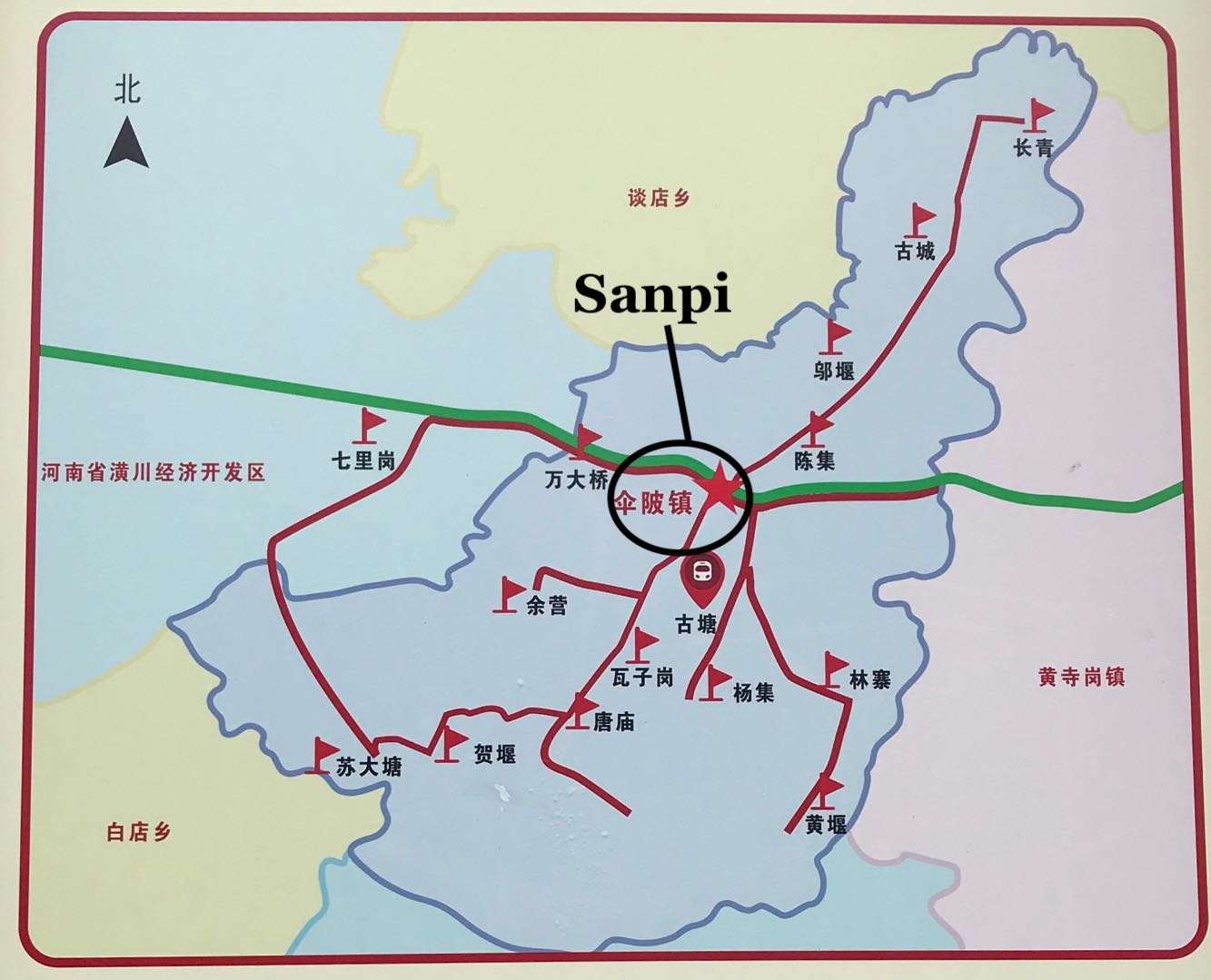

You’ve likely never heard of Sanpi, or met anyone from there. But that shouldn’t stop you from recognizing their stories.

Sun Jieying 孙杰营 and Lei Zhengya 雷正亚 were born and raised in Sanpi 伞陂, a town in Huangchuan County, Henan, about 230 kilometers from Wuhan. They were married there when they were teenagers. They made a living there on a small farm. They raised three children and four grandchildren there, over the course of 50 years of marriage. Today, Jieying is 66. He is a tall man who moves slowly and seriously. I’m told he used to have a horrible temper, though it seems to have mellowed in his old age. Zhengya, who is 68, is a small, plump woman who does not move slowly at all, and loves to crack jokes. They ask me to call them Grandpa and Grandma, so that’s how I’ll refer to them in this final story of our Love in Rural China series.

Previously:

Note: the names of the people in these stories have been changed.

“Have you eaten?”

Throughout the Chinese New Year holiday, Grandma was home busy preparing meals and cleaning up in between. She could either be found in the garden, kitchen, or front courtyard. Grandpa, meanwhile, was usually nowhere nearby — he would go about the village playing cards or mahjong, or smoke a cigarette on the stoop of the local market. He seldom returned home for the labored-over meals. And on the rare occasion Grandma and Grandpa passed each other in the courtyard or garden, they would hardly exchange so much as a glance.

On the second day of Spring Festival, the whole family was able to gather for a big lunch. All three of Jieying and Zhengya’s children and all five of their grandchildren had come home: Their oldest son, Jieting, his wife, and his children, Weiwei 薇薇 — recently engaged — and Changchang 昌昌; their daughter Jieping 杰平 — The Auntie of Sanpi — her husband, and their children, Xiaoqing 晓青 (Like Father, Like Son) and Xiaoyu 晓玉; and Jiebing 杰冰, their youngest son, his wife, and their nine-month old baby.

As everyone took their seats at the table and prepared to eat, Xiaoqing asked his mother, Jieping, if Grandpa would be coming home for lunch. Jieping looked at her mother.

“I don’t know if he’s coming,” Grandma said. “I didn’t talk to him this morning. Let’s just eat. The food will get cold.”

Everyone began to pour drinks and dig into the duck soup and freshly picked peppers stir-fried with eggs.

Nearly 20 minutes went by after Grandpa, slowly and silently, crept into the dining room. His eyes fixed on the food.

“Have you eaten?” Grandma asked. He shook his head no.

Grandma got up from her seat and left the dining room. She came back with a bowl full of rice and a clean pair of chopsticks. She gracefully gathered a big piece of duck, placed it over the fresh rice, and handed it to Grandpa. He sat down in Grandma’s seat, picked up the bowl of rice she left behind, and handed it to her. She stood behind him and continued to eat, occasionally reaching past him to get a piece of meat or bit of vegetables.

We ate in silence until Grandpa finally said: “Look how much oil is in this soup. Who could eat this?” He pointed to the stir-fried beans and celery on the table, “This is way too salty. Who could eat this?”

Grandma said nothing.

![]()

Later that afternoon, Grandpa woke up from a nap and moseyed out to the courtyard in his slippers. Grandma was crouched on a small stool alongside her daughter, Jieping, who was squatting on the ground, both of them cracking open fresh peanuts for dinner. Grandpa approached Grandma with what appeared to be a small tube of cream. He handed it to her, and she got up from her stool to let him sit.

“Does it hurt?” Grandma asked, looking at the back of his head, feeling around with the tips of her fingers. He shook his head no.

She applied some of the cream to her finger and gently rubbed it over the back of his head and down his neck.

As Grandma put the cap back on the tube, Weiwei walked into the courtyard, struggling to keep her arms around her nine-month old cousin, swaddled in a long, yellow fleece blanket.

When Grandpa looked up and saw his granddaughters, he was overcome with joy. His eyes lit up, his face softened, and his smile was so wide you could see all of his teeth (and the empty spots where teeth used to be). He stood, clapped his hands together twice, and opened his arms wide as he carefully inched toward Weiwei. Weiwei passed the baby over to him. As he gathered her into his arms, bouncing her up and down, Grandma snuck up behind him with the baby’s stroller. He nodded and laid her in it.

Grandma and Grandpa each put one hand on the stroller and pushed her down the driveway, their shoulders touching all the while. They laughed and chatted and made baby noises all the way down the road, where they stopped to introduce Yaya 亚亚 to their neighbors.

Last year I spent some time living with a family from Sanpi. I returned this year to spend Spring Festival with my host family and to explore a question I had been long curious about: What is love in rural China? What does it look like? What is made up of?

While some of the stories in this series may be mundane, I think I’ve come away with a better understanding of what an answer might look like. The “love” I saw rarely took the form of heart-to-hearts, words of encouragement, or even casual conversation. It sometimes even seemed paradoxical, taking the form of criticism such as “you’re failing,” “who could eat this?” and, “If you’re so smart, why are you only wearing two layers of clothes?” Sometimes it was ritualistic or transactional, like a mother leaving her daughter money after their first visit in nearly a year. For a minute, it might be tempting to question whether a love that is silent, critical, and transactional might be love at all.

But then we encounter a teenage girl who can’t contain her excitement at seeing her mom, a woman fighting through personal hardship to take care of the village’s children, a young couple about to begin their new life together, a 22-year-old boy who empathizes with his absent father, and a wizened old man warmed by the sight of his baby granddaughter, and I’m reminded of another truth: love, sometimes, is simply a matter of trying.

So, maybe “love” isn’t quite the right word. But it might as well be.