Chinese Corner: Three billboards across China — to fight gay conversion therapy

Chinese Corner: Three billboards across China — to fight gay conversion therapy

Three billboards and an uphill battle against gay conversion therapy

“中国版‘三块广告牌’”的双城之旅,为一种 “不存在的疾病”

The journey of three billboards in two Chinese cities, for a nonexistent disease

By Chén Lìyǎ 陈莉雅

February 1, 2019

In 1990, when the World Health Organization removed homosexuality from its list of mental illnesses, the declassification was widely hailed as a remarkable victory for gay rights. Slowly catching up to global trends, China in 1997 officially stopped treating homosexuality as a crime, and in 2001 it ceased categorizing it as an disorder.

However, in the following years, China’s deeply-ingrained and culturally-inspired stigma against homosexuality still persisted, causing many vulnerable individuals in the Chinese gay community to face societal discrimination and live with a sense of shame. As a result, a wave of institutions that claim to be able to alter people’s sexual orientation emerged. Through “gay conversion therapy,” these public hospitals and private clinics utilize a combination of methods, which usually involve humiliation and violence, in an attempt to turn gay men and women straight.

Globally, such therapy has been discredited by a host of major health organizations and denounced by most of mainstream society, but its existence and growth in China hasn’t garnered much critical attention. According to a research conducted by several LGBT rights organizations in China, as of 2017, there were around 112 institutions across the country that publicly advertised their services of conversion therapy. A 2014 study by Beijing LGBTQ Center found out that of 1,653 respondents, 151 of them said they had contemplated seeking such therapy, mostly because of pressure from their families and people around them.

In order to raise public awareness about the unchecked proliferation of conversion therapy, in January, three Chinese men, artist Wǔ Lǎobái 武老白, curator Zhèng Hóngbīn 郑宏彬, and policeman Lín Hè 林壑, together launched a crowd-funded campaign letting three trucks hit the road, each one bearing a message: on the first, “Cure a disease that is nonexistent”; on the second, “The Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders still has sexual orientation disorder”; and, lastly, “It’s been 19 years. How come?” The three messages are quotes from Lin’s diary, in which he wrote about his frustration and struggles as a gay man.

The idea, according to Wu, was inspired by the Oscar-winning movie Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, which tells a gut-wrenching story of a mother who seeks justice for her murdered daughter by paying for an ad across three billboards in a small town to shame local police for their negligence and incompetence. As part of the campaign, during the trip, the vehicles made stops at treatment centers, where Wu, who’s straight, pretended to be a closeted gay man willing to receive therapy. He documented his conversations with self-proclaimed therapists.

So far, the trucks have toured in Shanghai, Nanjing, and Jinan. And the campaign is ongoing; as more people become aware of it and make donations, it will allow the trucks to travel in more cities. Meanwhile, the three men are working on a documentary based on this experience and encouraging people who have undergone conversion therapy to share their stories online.

This story by Chen Liya is a long one that chronicles the incredible campaign, which was off to a promising start but still has a long way to go.

Inside the lives of millennial hermits

被逼下终南山的修仙90后

Those born in the 1990s who are forced to leave the Zhongnan mountains

By Yuán Lín 袁琳

January 14, 2019

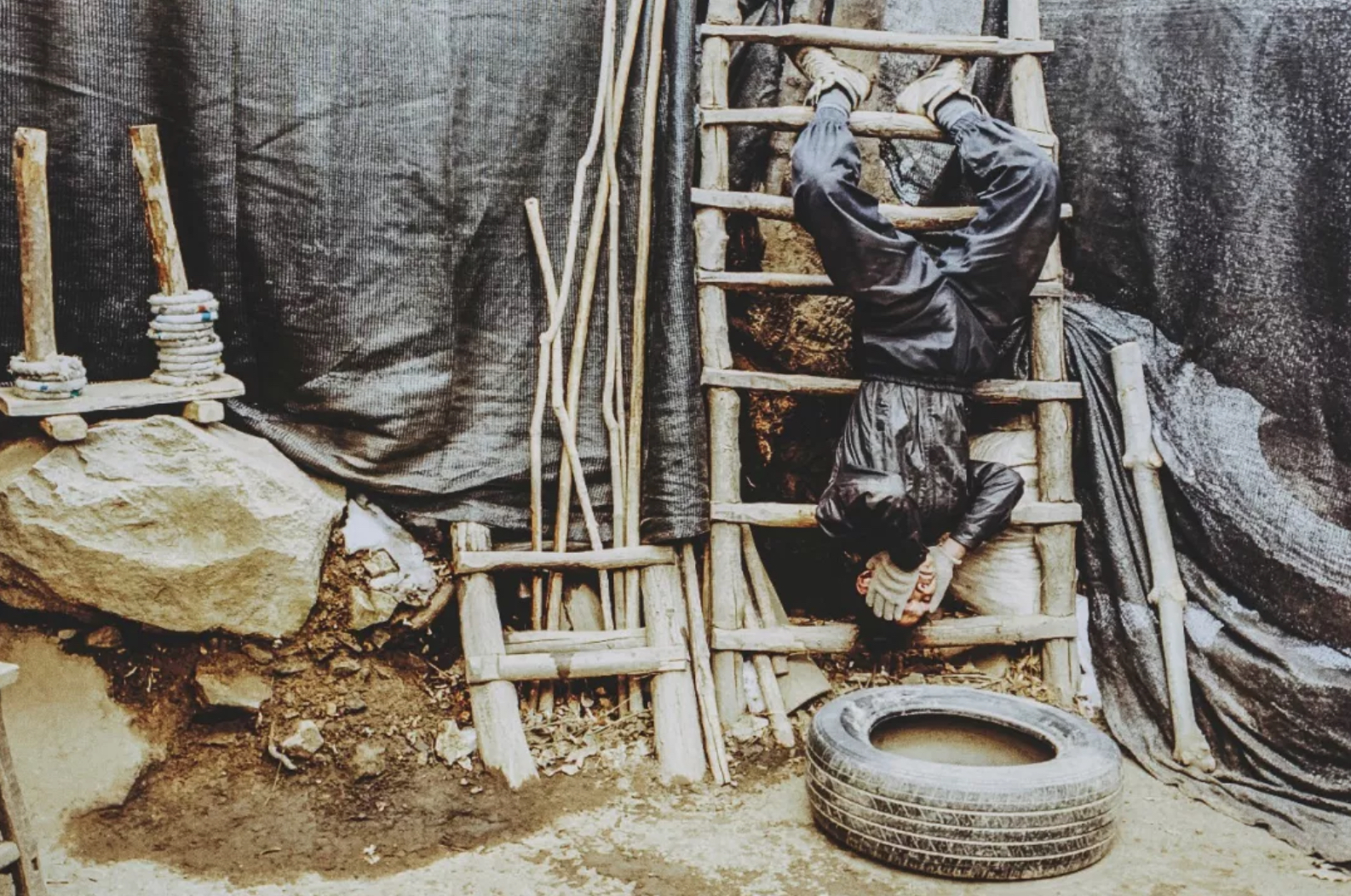

Millennial burnout is real, leading some young adults to withdraw from the exhausting reality of mounting social pressures. In China, the Zhongnan mountains, which have been associated with Buddhism and Taoism since ancient times, have become a popular destination for burned-out millennials to live in isolation. Deep in the mountains, young people there find peace by cutting ties with the outside world and leading reclusive lives.

In the article, author Yuan Lin dives deep into the millennial hermits’ community in the Zhongnan mountains, trying to understand what prompted them to shut themselves away and find out whether they see their retreats as a failure.

Related reading and watching:

- 中产“跑”进佛学院 The middle class is “rushing” into Buddhist academies

- Video: Summoning the Recluse: Chinese millennials take up the hermit’s life

- Video: Assignment Asia: A modern-day hermit in China

Li Xueqing on how to entertain people while struggling with depression

李雪琴:我很痛苦,但我想让别人快乐

Li Xueqing: “I feel distressed, but I want others to be happy”

By Zhāng Wěichéng 张炜铖

February 1, 2019

Six months ago, Lǐ Xuěqín 李雪琴, a Peking University graduate in her 20s, dropped out of a Master’s program at New York University due to severe depression. Back in China, out of pure boredom, she joined the short-video platform Douyin and started posting random videos dedicated to the controversial pop star Kris Wu 吴亦凡. As a longtime depression sufferer, Li said her fandom of Wu was largely fueled by her envy for Wu’s carefree persona, a personality trait that she has craved for since a child. Li never aimed for viral success, but Wu’s cheeky response to one of her videos made her an internet celebrity overnight. Now, with 3 million followers on Douyin, Li is trying to leverage the platform to delight her audience, even though she’s still constantly grappling with suicidal thoughts.

“I know the joy I bring to people is not long-lasting. I can make people happy for two minutes but I am unable to make people feel fulfilled. But I still think what I’m doing now is a good deed,” Li wrote in this personal essay. “The hustle I’m experiencing now is my way to fulfill other people’s needs and expectation. I’m frustrated by my loss of private life but I want everyone to be happy. So I chose to sacrifice myself to please others.”

The only student at school

一个老师和一个学生的学校

A teacher, a student, and their school

By Zōu Bìyǔ 邹璧宇

February 15, 2019

In a tiny, remote village in China, there is a school that only has one student and one teacher. The student, Wáng Lóngzé 王龙泽, lives with his widowed father, who can’t afford to leave the village and give his son better education. Meanwhile, the teacher, Lài Zhēnyuán 赖贞元, is determined to teaching the only student he has until Wang’s graduation.

The myth of young adults in Chinese small towns

被误读的小镇青年

Young people in small towns, the misunderstood

By Shěn Shuàibō 沈帅波

February 12, 2019

If the enormous success of Pinduoduo and Kuaishou has taught us one thing, it’s that the future of China’s consumer economy greatly relies on young adults in small towns outside the country’s first-tier cities. For a long time, they were considered as lower-class by metropolitan elites, who taunted them for their lack of education, financial power, and cultural influence. But as the so-called middle class in major cities went through a consumption downgrade and an identity crisis last year, young adults in rural China revealed their massive buying power, which forced a number of internet giants to adjust their perceptions of this demographic.

In this essay, blogger Shen Shuaibo argues that to truly understands young people in Chinese small towns, entrepreneurs and urban elites need to abandon their arrogance and bias toward them. “To put it blatantly, the reason why many people started to care about those young adults is because they saw financial potentials in them. But sorry, you will never make money from them if you view them from a condescending standpoint,” Shen wrote. “Remember, they, actually, constitute the majority of this country’s population.”

Below are some of the best things that caught my attention this week:

- 「伏弟魔」,独生子女永远不懂的存在 ‘Brother-assisting demons,’ an existence that only children can never understand

The prevalence of the phrase has sparked an ongoing debate about what it entails to be the only daughter in a Chinese family with strong preference for sons. In this article, four women give their personal accounts of growing up in such a family and how they grapple with the parental and cultural pressure to support their brothers in every possible way. - 李诞一个人的成功,是一个社会的失败 Li Yan’s success is a failure of our society

An exploration into how comedian Li Yan became a cultural phenomenon for Chinese millennials by selling a concept of Buddhist nihilism. - 从留守儿童到百万网红,厨师王刚的奇幻漂流 From a left-behind child to a celebrity chef, the legendary life journey of Wang Gang

“This is by no means a hero’s story. Rather, it’s a story of how Wang confronted himself and his family in a prolonged and massive failure.” - 一位清华高材生的死亡直播 The Tsinghua graduate who livestreamed his suicide

- 命理“生意” The ‘business’ of fortune telling

- 79岁老人和他的动物园 The 79-year-old man and his zoo