The tragic end of Shi Hui, Maoist China’s most promising actor-director

Persecuted and misunderstood, Shi Hui was one of many individuals swept up and destroyed by the Anti-Rightist Movement. Chinese cinema is irrevocably poorer for it.

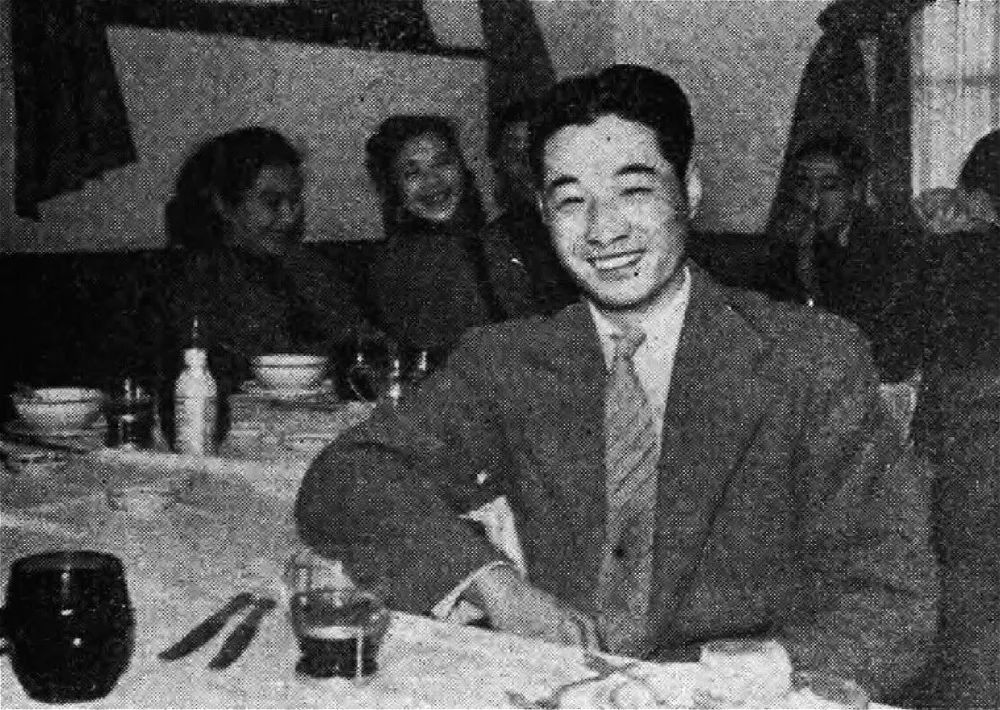

During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Shi Hui 石挥 was one of the most popular actors in China. Shi’s range was wide, and he portrayed a variety of mostly lower-class characters during his film career, playing a school principal, a tailor, a peasant soldier, a pimp, and even a (white) American capitalist. Whatever his role, Shi always brought depth and humanity to his characters, whether they were heroes or not. His performances in movies like Miserable at Middle Age 哀乐中年 and This Life of Mine 我这一辈子 were brilliant, and today, both movies still top lists of the most-acclaimed Chinese movies.

The naturalness with which Shi played his characters might have had to do with his own humble background. Shi Hui was born Shi Yutao 石毓涛 in 1915, in the city of Tianjin. His family later uprooted to Beijing, and their financial difficulties forced Shi to leave school and head to work when he was only 11 or 12. The low-paying jobs Shi did during his youth left him very bitter. In Shanghai, he worked on a train, later moving to Beijing to sell tickets at a movie theater. Long after Shi’s death, when American historian Paul G. Pickowicz interviewed one of Shi’s friends, the man recalled that “People with money and position abused him, and he never forgot it. He hated the world and he was incredibly cynical… He didn’t believe in anything.”

Shi might not have been interested in politics, but he did come to love the spotlight. In his early 20s, Shi joined a theater troupe and began to act. His connections led him to Shanghai in 1940, and within only a few years in the city, theatergoers were championing Shi as the “King of the Stage.” Shi made his first appearance in a movie in 1941, but his transition from stage to screen really didn’t take off until his roles in Phony Phoenixes 假凤虚凰 (1946) and Long Live the Mistress! 太太萬歲 (1947). These two classics were made by the Wenhua Film Company 文华影业公司, a studio specializing in contemporary, humanist fare. For most of his early film career, Shi would be closely associated with Wenhua and its repertoire of talent.

1949 was an important year for Shi. He continued his box office success with Miserable at Middle Age, a comedy-drama starring Shi as a widowed principal with a special devotion for the school he’s been running the past decade or so. Shi also wrote and directed Mother 母亲 that year, a social drama about a mother who’s left with only a son after her husband commits suicide and her daughter dies young. It was a competent enough debut, but the following year, Shi would make the masterpiece of his career, the epic biography This Life of Mine. Shi’s adaptation of this Lao She 老舍 novella featured himself in the lead role, playing a kindhearted Beijing policeman who struggles to understand the political turmoil around him. Living his life from the last years of the Qing Dynasty to the end of the Chinese Civil War, Shi’s nameless cop does everything right, only to be repeatedly abused and left to die in the streets of the city he so long tried to protect.

The ending of This Life of Mine is tragic, yet unabashedly pro-Communist, suggesting that better days were surely ahead for China. At first, Shi tried to get on the good side of the Communist Party. He did charity work for veterans, and helped lead a march of movie celebrities in favor of the PRC in October 1949. This Life of Mine was meant to be a tribute for the PRC, and Wenhua and Shi tried paying further homage with works like Spring of Peace 太平春 (1950) and Platoon Commander Guan 关连长 (1951). Unfortunately, both these attempts starring Shi were political misfires.

In the former, Shi was a helpful tailor who initially doesn’t understand the Communists. His character is completely changed by the end, but party critics condemned the ideological wrongs of the movie so harshly that it stopped being screened. The director publicly apologized, and Shi stepped away from the controversy by writing a pro-Communist essay, essentially claiming that the art world had dropped its bourgeois decadence, and thanks to the Communists, realized its true purpose in becoming revolutionaries and helping the people. Shi acted in several movies after this scandal, but whatever face he saved with his essay was demolished by Platoon Commander Guan. Wenhua thought this patriotic war piece couldn’t possibly offend anyone, but critics had other feelings about Shi’s portrayal of an unrefined, realistic peasant soldier.

Shi was never easy to get along with, and after his work came under the fire of party critics, work became increasingly scarce. In 1954, he was able to direct Letter with Feather 鸡毛信, a war story about a boy who is tasked with delivering a secret letter to the Communist Eighth Route Army during a battle with the Japanese. The movie was popular with audiences, and surprisingly enough, was awarded a Ministry of Culture prize in 1957. His next work as a director, a filmed opera entitled The Heavenly Match 天仙配, made quite a sensation in Hong Kong in 1955. The same year, he married Tao Baoling 童葆苓, an actress who had appeared in Mother.

The Hundred Flowers Campaign briefly loosened the Communist Party’s chains on the Chinese film industry. In his last role, Shi played a part in the 1957 movie Endless Passion, Deep Friendship 情长谊深. Meanwhile, he worked on a screenplay, a political allegory about the passengers on a boat called Democracy No. 3 trying to navigate through a thick fog. This ended up being Night Voyage on a Foggy Sea 雾海夜航, Shi’s last piece of work.

Like the satirist Lü Ban and other contemporary filmmakers, Shi became a target when the Anti-Rightist Movement erupted. In a struggle session, an unflattering party member in Night Voyage on a Foggy Sea was taken as an attack on the Communist Party itself. Nobody dared to risk their reputation defending Shi. Humiliated, Shi was sick of the treatment he had endured. On an unknown date in December 1957, Shi got onto a boat in Shanghai, jumped off the deck, and drowned himself in Huangpu River. During his “disappearance,” the film industry and critics continued to vilify Shi in the press. He remained missing until April 1959, when his body was finally found and identified.

At the time of his suicide, Shi Hui was only 42. The Communist Party hushed reports of his suicide, and his reputation wasn’t rehabilitated until after the Cultural Revolution. Shi’s early death undoubtedly ranks as one of the great tragedies of Chinese cinema, and had his career not been suppressed so heartlessly, perhaps there’s no telling what this legendary actor-director might have accomplished in his later years.

Film Friday is The China Project’s film recommendation column. Have a recommendation? Get in touch: editors@thechinaproject.com