A $22 million soccer museum in China makes claim as the ‘birthplace of football’

The Linzi Football Museum in Zibo, Shandong Province doesn’t just commemorate the sport of soccer. It’s pushing an entire nation’s footballing fantasy.

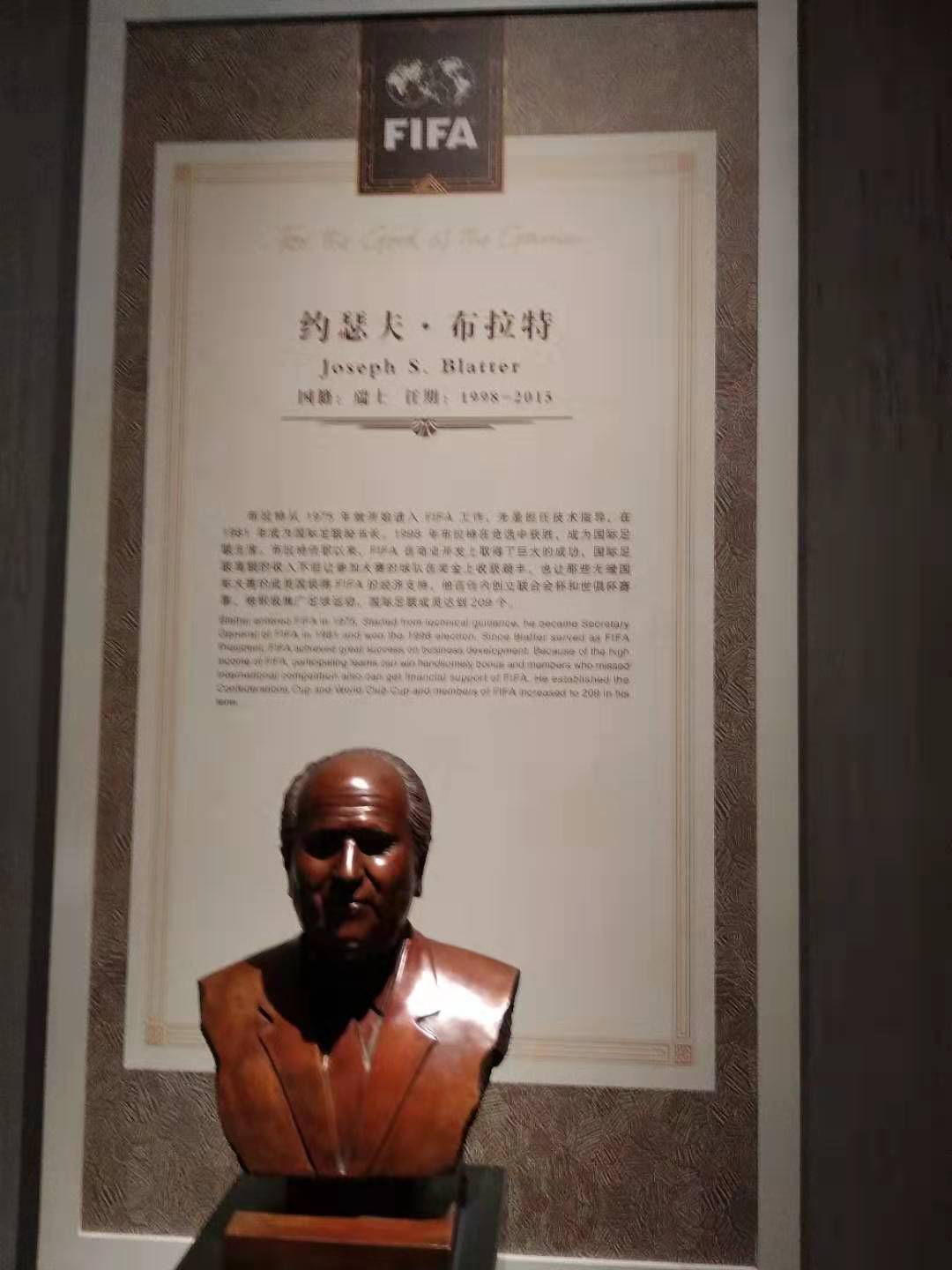

Sepp Blatter is not a popular man. The former president of FIFA, football’s world governing body, is currently serving a six-year ban from all footballing activities for dodgy payments made while presiding over an organization so corrupt it could make Russia’s Olympic Committee look clean.

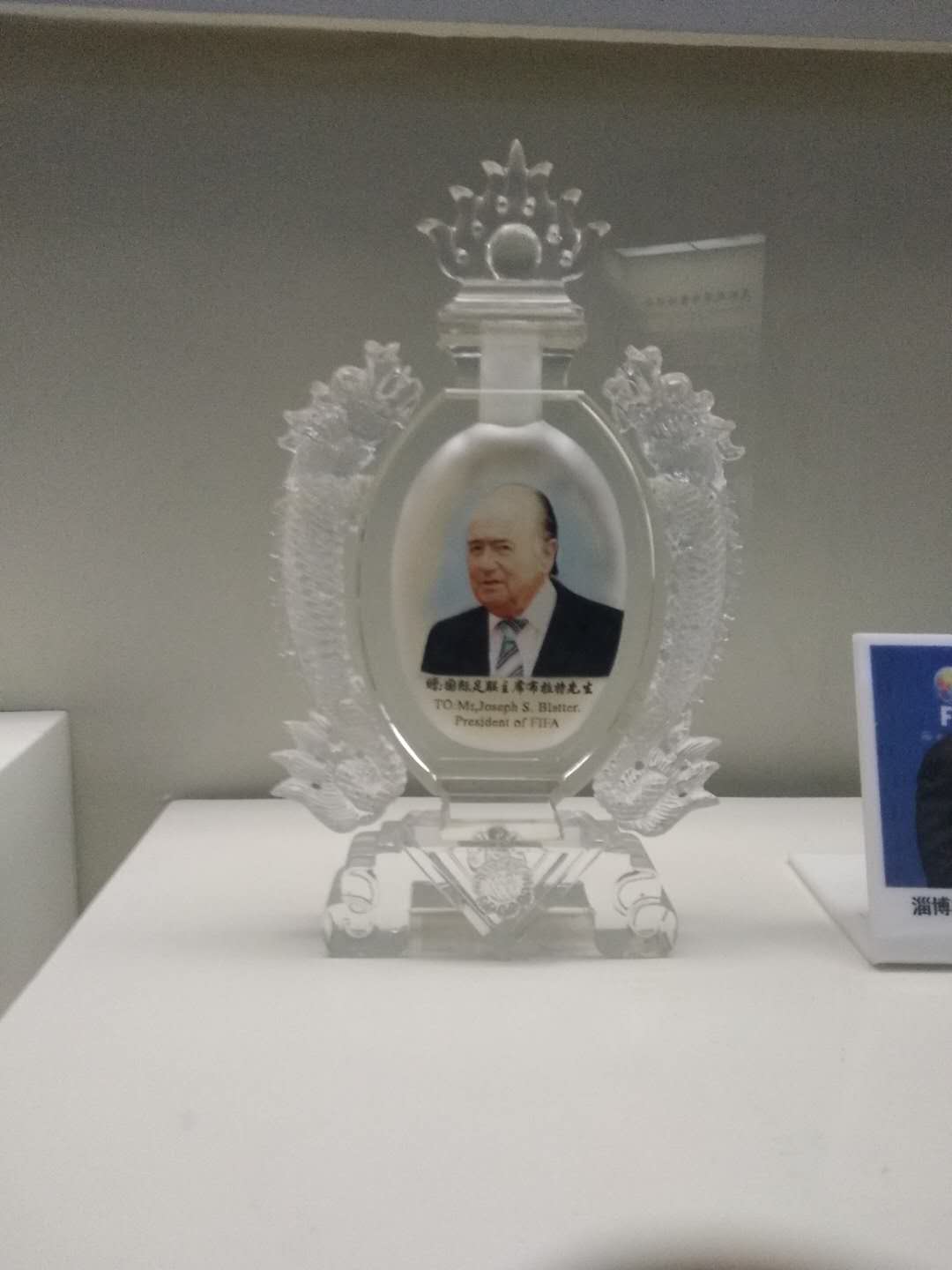

But in one small corner of China, Blatter’s still doing pretty well for himself. In Zibo, a prefecture-level city of 4.5 million in Shandong Province, his bronze-cast signature continues to grace the entrance of the Linzi Football Museum (临淄足球博物馆 Línzī zúqiú bówùguǎn). Pictures — and one hefty bust — of Blatter are littered throughout the building. It’s understandable: the museum was largely built in response to Blatter’s 2005 announcement that Linzi was the birthplace of world football some 2,000 years ago.

Fourteen years and tens of millions of dollars later, the museum still stands as a testament — not so much to ancient China’s role as the granddaddy of world football as to a marriage of convenience between a FIFA lusting after the lure of Chinese market riches and a Chinese government committed to using history in the service of its economic and footballing development efforts.

To cut to the chase: it’s hard to claim with certainty that Cuju 蹴鞠 — a game played in ancient China by kicking around a ball — is the progenitor of modern Association Football. David Goldblatt, whose The Ball is Round is the authoritative work on football’s history, identifies a game played by Australian aboriginals as “likely to be as old and probably older than Cuju.” There’s probably a particular way of defining what makes an ancient game “football” — does it have goals? teams? is handling allowed in some cases? — that might allow you to include Cuju and exclude Marn Grook, but the distinctions seem mostly semantic.

Perhaps more importantly, there’s no clear genealogical line connecting Cuju to the formation of Association Football in 19th century Britain. The museum’s Cuju exhibit gestures vaguely at evidence that during the Tang and Sui dynasties, the game spread within Asia and along the Silk Road, but it’s hard to get from there to football as it was practiced in the UK.

None of this stopped Blatter from enthusiastically naming Zibo the birthplace of world football in 2005, an event the museum memorializes in its very first room, a small circular chamber bathed in blue light with a faux-starry-night ceiling. A clip of Blatter saying, “The game — as we know it now, Association Football — was already played, and it was played in the province called Linzi,” plays on repeat. Handwritten notes from then-FIFA officials like Blatter, Urs Linsi, and Chuck Blazer thank Linzi for giving football to the world. Many of those officials have since been implicated in the massive ongoing corruption investigation of FIFA.

Blatter’s fixation on Cuju was perhaps not born of innate historical and archaeological interest.

“Blatter’s fondness for China was, as we know, expeditious. He saw it as the largest and fastest growing economy — football’s final frontier, so to speak. So he did his best to curry favor,” Ellis Cashmore, author of a book on corruption in football, told the Daily Telegraph in 2015.

Just as FIFA had financial interests in China, China has political interests in FIFA.

Though Blatter is gone, ousted by the fallout from a massive corruption investigation, FIFA’s relationships in China remain strong. As global suspicion of FIFA and the Russian state spooked sponsors ahead of the 2018 World Cup, Chinese companies picked up some of the sponsorship slack.

They did not necessarily do this just to be nice. Just as FIFA had financial interests in China, China has political interests in FIFA.

“China is not trying to rescue FIFA but to influence its decisions over the next 10 years,” sports sociologist Simon Chadwick told the New York Times last May. “And the top priority, arguably, is to help China win a bid to host the World Cup.”

Ever since Xi Jinping said in 2011 that he hoped China would qualify for, host, and win the World Cup by 2050, private businesses have been clamoring to get involved with the sport, buying Chinese Super League teams and shelling out massive wages to lure top players. (Shanghai SIPG pays Oscar, a Brazilian midfielder, over $25 million per year.) The state has an ambitious, statistics-laden plan to build tens of thousands of fields and training centers and create 50 million regular soccer players in China.

Academics like Chadwick and journalists have been quick to suggest parallels between this top-down state-driven approach to football success and China’s economic growth model. Both risk using massive initial capital outlays at the expense of fostering or allowing for grassroots growth. (The football dream is faring far worse than the economic one; China’s men’s team currently sits 72nd in FIFA’s world rankings.)

While Linzi’s museum predates the China Football Dream, as it’s come to be known, it nevertheless fits into it quite well. (Xi Jinping makes a few customary appearances, giving a Cuju ball to then-Prime Minister David Cameron or admiring an exhibition with a representative from the Olympic committee.) It also serves as an example of the possible pitfalls in China’s government-led growth efforts. The museum sits on the north edge of a mammoth complex housing several museums of Qi culture (Linzi was capital of the Qi kingdom from 1046 BC to 221 BC). If the football museum alone, as reported by the Daily Telegraph, cost around $22 million, the entire complex must have cost several times that. On the day of my visit — admittedly in the middle of the touristic dry season — I saw just six other visitors over the course of my two-and-a-half hours there. The other museums appeared similarly deserted.

All this said, the museum is, on the whole, pretty enjoyable. Spanning roughly 2,500 meters over two floors, the museum features three exhibits (one on ancient Cuju, one on contemporary world football, and one on the modern Chinese game), a replica Cuju court nestled in its internal courtyard, and a very empty second-floor cafe.

The first of the museum’s exhibitions, the one focused on Cuju itself, is its best. Using Cuju as a way to look at the culture of the Qi kingdom writ large, the exhibition is handsomely done, featuring several clay miniatures of villages or military training grounds where Qi citizens play Cuju.

The modern football exhibition, while a little disjointed, is entertaining. Lacking much original museum-worthy material, display cases show miniature prints of the Mona Lisa and the School of Athens, an edition of the Decameron (all to show the supposed influence the Renaissance had on the eventual development of European football), a life-size reproduction of a room in a Freemason’s tavern (for reasons unknown), and modern goalkeeper gloves, shin guards, and socks (all of which are available for purchase from Nike or Adidas.)

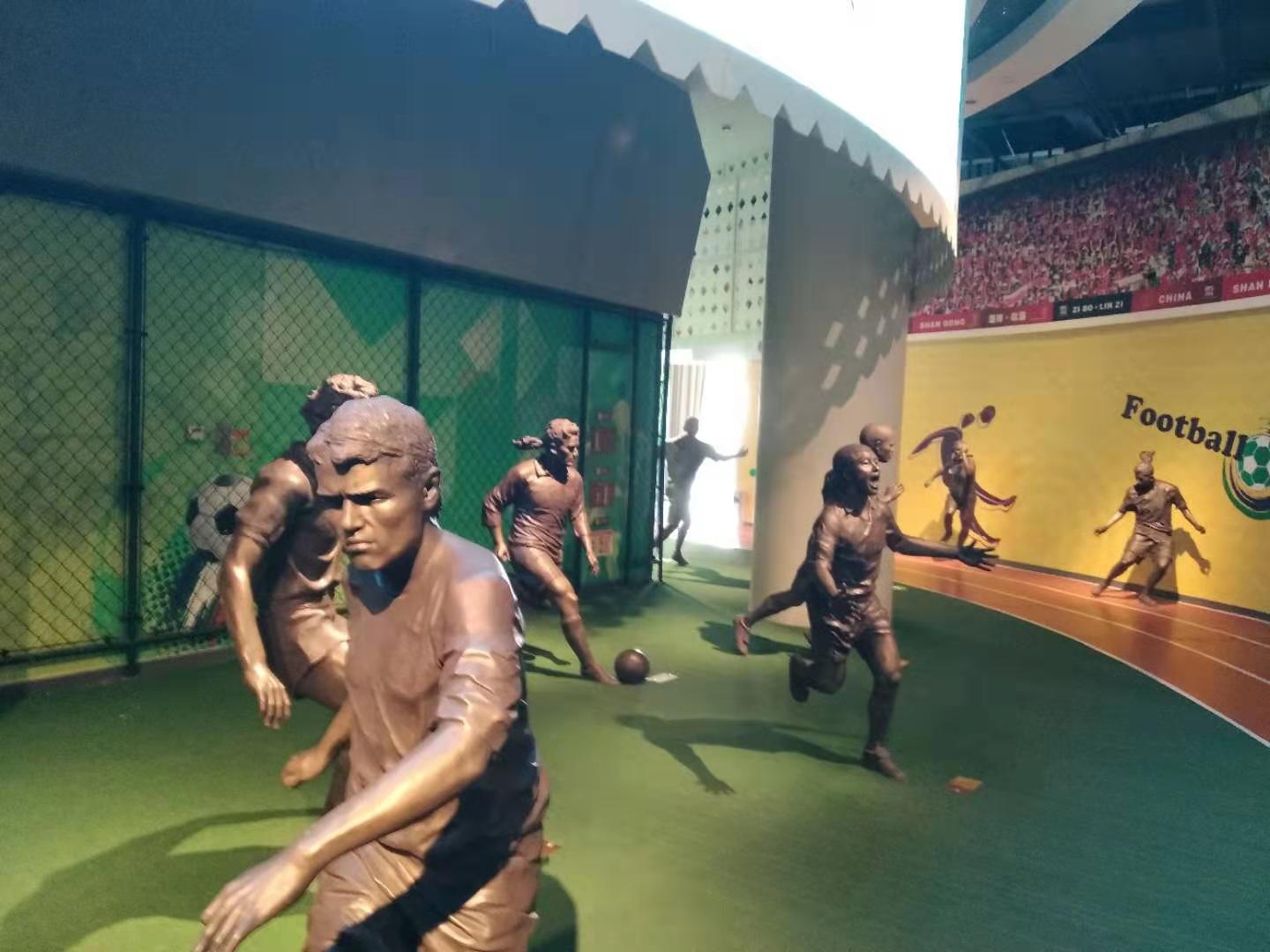

The exhibit, which includes a room dedicated to all the presidents of FIFA, spills out into an indoor track where children can, for a fee, play some soccer-related carnival-type games. Around the track are life-size bronze-cast figures of football legends and a plastic full-size model of David Beckham flanked by two scantily clad, midriff-baring female footballers.

The last and shortest exhibit, on the modern Chinese game, makes the most explicit link between the China Dream and its football-focused version. Its preface describes the way modern football has been “spreading back to its distant homeland” after a period of Chinese “backwardness,” an echo of the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation” that Xi promotes. The exhibit, which features very little English wall text, displays old photographs of the first Chinese teams in concession areas like Tianjin. Reproductions of football-related propaganda and cartoons precede short summaries of the performance of the men’s and women’s teams in recent years. The women’s team currently sits 15th in world rankings and fairly consistently makes the knockout rounds of tournaments. In 1999, they were runners-up to the U.S. team in the World Cup.

The men’s team has performed much worse. Their only appearance at the World Cup, in 2002, saw them lose all three games without scoring a goal. Nevertheless, the museum faithfully records the men’s team’s “football dream of the World Cup.”

The dream hasn’t gotten much closer recently. After crashing out of the 2018 Asia Cup against Iran, China parted ways with its well-compensated manager, former World Cup-winner Marcello Lippi. Still, the museum isn’t giving up hope yet.

“Regardless of wind and rain,” a text panel concludes, “Chinese football is on the road to excellence.”