1973: When kung fu ruled the American box office

In 1973, American movie-goers could not get enough of Hong Kong cinema, with the top three spots at the box office, at one time, occupied by Fists of Fury, Deep Thrust, and Five Fingers of Death. While the craze died down, the legacy of the kung fu genre has not.

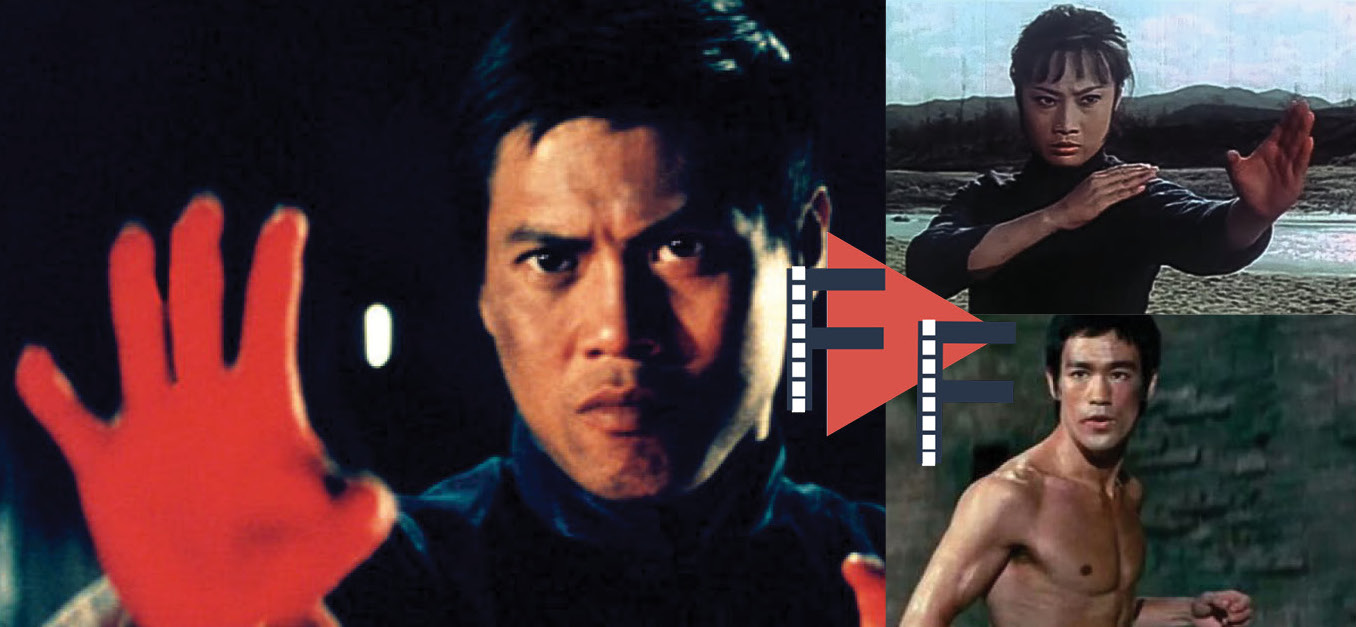

Main image: Five Fingers of Death; top right: Deep Thrust; bottom right: The Big Boss (Bruce Lee)

In March 1973, Warner Brothers made the surprising choice to release a film from Hong Kong to American theaters. The studio had great success the previous year with its TV show Kung Fu, and to capitalize on that, it began to import real kung fu flicks Its first movie featured all the staples we’ve come to associate with kung fu flicks: an underdog lead, criminals, revenge, melodrama, fast-paced, spectacular fights — and terrible English dubbing.

Most American critics weren’t impressed, but the Hong Kong import was a hit with audiences. Despite its limited release, the movie was the highest performing draw that week on the box office charts. It ended up staying on the charts for nearly three months, and during one week in April, managed to climb back up to the first spot. In a favorable review, Variety commended the movie for its “powerful” directing and “colorful production values.” The leading man, an actor born outside of China who was an actual martial artist, was also praised. His role would quickly launch him from an unknown actor to an international star.

Hearing this in 2019, you’d be forgiven if you thought I was referring to Bruce Lee and one of his classic kung-fu movies. It wasn’t Lee and The Big Boss 唐山大兄 that dominated the American box office that March, but Indonesian-born actor Lo Lieh 罗烈 and his Five Fingers of Death 天下第一拳. While Lee is massively important in the history of kung fu film, Five Fingers of Death deserves credit for introducing the genre to a number of Western moviegoers. It was something new, something more exciting and violent than domestic features. A man has his eyes gouged out in one scene, for example, while the final fight shows the hero punching an evil samurai so hard with his glowing red fists that the impact breaks a stone wall:

It’s memorable enough that a single Hong Kong movie was able to top the American box office, but Five Fingers of Death wasn’t alone that year. It sparked a craze for kung fu, and American audiences just couldn’t get enough. Lady Whirlwind 铁掌旋风腿, a revenge story starring hapkido expert Angelo Mao 茅复静, was released to similar success. For the American market, the movie’s name was retitled Deep Thrust, as a nod to the infamous Deep Throat. Soon, dozens of kung fu movies were playing in American theaters, sometimes under alternate names or titles that were wildly different from the Chinese originals.

The Big Boss was just one of the victims of this confusing practice. In his first big martial arts role, Bruce Lee plays Cheng Chao-an, a worker at an ice factory that’s being used for drug smuggling. Due to its drug-related plot, the American distributor planned to retitle the movie as The Chinese Connection, ripping off the Gene Hackman thriller The French Connection. Lee’s second major movie, Fist of Fury 精武门, which played in New York theaters in November 1972, was also picked up for national distribution. There was a mix-up, however, and The Big Boss took the name Fists of Fury, while the real Fist of Fury was accidentally released as The Chinese Connection.

On May 16, the top three spots at the box office were occupied by Fists of Fury, Deep Thrust, and Five Fingers of Death. When The Chinese Connection was released in June, it climbed up to the top of the charts on the 20th of that month. Even though Lee is a pop culture god today, he wouldn’t actually live to see his popularity in the United States. A month after the American release of The Chinese Connection, Lee died of a cerebral edema in Hong Kong. While already a celebrity across Asia, Lee’s fame in the West was so small that obituaries in papers like The Los Angeles Times called his movies “Eastern westerns,” and mistakenly credited him as the “hero” of Five Fingers of Death.

At the time Lee died, the Hong Kong-Hollywood co-production Enter the Dragon 龙争虎斗 was envisioned as his great American debut. It was released after his death, first in Hong Kong and then in the United States in August. Playing a Shaolin monk, Lee’s character is enlisted by a British secret agent to join a martial arts tournament. The competition, held on a drug lord’s private island, also gives Lee an opportunity to catch his sister’s killer. It’s an action masterpiece, and while Lee is the star of the show, he’s backed up by a stellar cast of other professional martial artists. Enter the Dragon proved to be just the hit Lee wanted during his brief life, earning $25 million in the U.S. and $65 million internationally for a total gross that would be equivalent to $500 million today.

Enter the Dragon turned Lee into a posthumous star, and while his reputation would only grow in subsequent years, the movie was the peak of the 1973 kung fu boom. By the winter season, Hong Kong productions could only be found in the box office charts within the top 50 movies. By February 1974, they’d completely vanished from the top ranks of the box office. It was a short but impressive run. As scholar David Desser notes in an excellent article about the subject, “…during the height of U.S. movie-going, the spring and summer season, Hong Kong imports performed not only far better than films from any other country by far, but for about one-fifth of the season Hong Kong films outperformed Hollywood’s own product.”

In spite of its hasty reign, America’s kung fu obsession left a lasting impression. For some viewers, the kung fu fad was undoubtedly exotic, yet its anti-establishment and anti-imperialist themes deeply resonated with African-American fans and members of the counterculture. Blaxploitation movies like Black Belt Jones (1974) and The Black Dragon’s Revenge (1975) were homages to the kung fu genre, with the former starring Enter the Dragon actor Jim Kelly. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, the genre’s influence extended to the work of cult action stars like Jean Claude Van Damme, Chuck Norris, and Steven Seagal. It’s no secret that big directors like The Wachowskis and Quentin Tarantino have drawn heavily from the genre as well. In 2001, two years before his love-letter to Asian action cinema Kill Bill premiered, Tarantino declared in an interview that “martial arts films to me are one of the sub-genres of my life. To me, that is like one of the greatest staples in cinema. And for half the planet, it is too.”

Film Friday is The China Project’s film recommendation column. Have a recommendation? Get in touch: editors@thechinaproject.com