Voices from China’s lesbian community

This story originally appeared on 66hands, and is republished here, with minor edits, with permission.

When it comes to gay rights, China has come a long way in the past two decades, but it has a long way to go. As recently as 2013, according to a public opinion poll, 57 percent of surveyed Chinese citizens said society should not accept homosexuality. If you identify as a Chinese lesbian and reside in the People’s Republic of China, it is forbidden to do the following: marry another woman, adopt a child with another woman, join the military, donate blood. There are also no protections against employment discrimination.

LGBTI is an abbreviation for “lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex” individuals. But this story will focus on Chinese lesbians — because during my research, many articles I came across were on gay men, and the majority of people willing to speak to me openly about homosexuality in China were men.

Clearly, the girls need a louder voice — and it is this voice that deserves to be listened to, understood, and empowered. Given the tremendous outpour of female voices who have declared Lean In, #MeToo, and Time’s Up — to name a few — and considering that no one ever stops running at the start of a marathon, I’ll be focusing on the Ls of LGBTIs.

Q, 22, Fuzhou

Many Chinese lesbians seem to be more focused on their personal relationships rather than building the community and lobbying for change — because they have no hope for change.

I was 14 and in high school; I’d liked this girl for two years but knew there was something about my feelings for her that didn’t match how my classmates saw each other. I turned to my mom for an explanation — she suggested counseling.

I’m now 22 and live in Shanghai. I’m in my final year of university, majoring in marketing. I work part-time in one of Shanghai’s lesbian bars and volunteer for Qmmunity, an LGBTI community set up in 2014 by an American expat.

The Chinese lesbian community is more WeChat groups with girls looking to meet other girls together in groups. Many Chinese lesbians seem to be more focused on their personal relationships rather than building the community and lobbying for change — because they have no hope for change.

In all the lesbian WeChat groups, few are above 35. I guess they all get married and don’t show up anymore. I’ll do the same; it’s too cruel to my parents otherwise. When they were growing up, they were starving. The life they had isn’t even remotely comparable to the one I have now.

A part of me wants to lead my life the way I want, but I can’t do that to them. I have four options: I never get married, I get married abroad (and stay abroad indefinitely), I marry a man I am neither attracted to nor love; or I enter into a “fake marriage” (形婚 xíng hūn) – where a gay couple marries alongside a gay couple, enabling both couples to stay with their same-sex partners while enjoying the same liberties as a heterosexual couple.

My girlfriend is from a small village outside of Anhui, is the youngest of five children, has illiterate parents, is completely financially independent — and can do exactly what she wants. I envy this; I recently moved out of my family home to live with friends only for my parents to find an apartment right next to mine.

R, 27, Zhejiang

I don’t think Chinese tradition is compatible with homosexuality.

During primary school, I distinctly remember watching a Doctor Who episode whereby Captain Jack Harkness, who is pansexual, kisses the Doctor. I’d always thought girls were cuter than boys, but it wasn’t until then that I realized things could go this way.

I’m now 27 and live in Shanghai, where I work as a professional writer for comic and anime companies. I’m a huge nerd, so most of my friends are from comic-cons and straight. I’m single and have had a brief relationship with a woman, but I wasn’t ready and messed the whole thing up.

Currently, I’m concentrating on work, as I have neither the time nor emotional energy to maintain a relationship. I have mild depression and anxiety but tend to bury my emotions deep down and ignore them, as this helps me get on with my life. Even though there is technically help available, you run a risk, as it is so easy to become a qualified therapist and mental illness is still relatively new to China.

I left my hometown with a coming-out plan: Stage 1, find a job; Stage 2, become financially independent; and Stage 3, come out to my parents — but I’m stuck at the final stage. I know my mother would break down if I came out to her, and I don’t think I’d be able to handle the consequences. I think for a lot of queers in China, a contributor to mental health issues is the fear of rejection from our families — some of us can, but I just doubt whether I could myself.

I don’t think Chinese tradition is compatible with homosexuality. We are raised in a family-centered society, told that our life not only belongs to ourselves but that of our parents and wider family. So being ourselves means being rejected (and sometimes exiled) from our family. It’s like ripping a plant out of the ground, snapping the roots and leaving the beautiful plant itself to wither and die.

J, 35, Shanghai

I get to express my sexuality and be exactly who I want to be.

It took me 10 years to truly feel comfortable in myself; in high school I was popular, as I got good grades and was good at sports. I think my dyke appearance added to my popularity, as people were intrigued by my differences. But at the time, I couldn’t access any material to educate myself on why other people didn’t feel the same attraction as I did for the same sex.

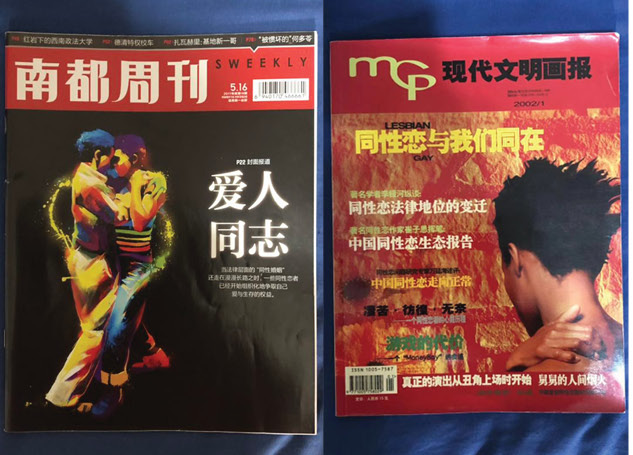

I was left confused and in the dark until my final year in high school, when I came across a magazine featuring homosexuality (同性恋 tóngxìngliàn) on the front – and I realized I was normal. Then came the internet, which not only started to completely shake up the lives of Chinese people, but for me personally, it enabled me to devour any information on homosexuality I could get my hands on. That truly had a profound impact on my self-awareness, sexuality, and happiness.

I’m now 35 and live in Shanghai with my father. I came out to my family and friends years ago; everyone accepted me, and my friends’ parents even try to arrange blind dates for me. I started learning English in preschool, so I’ve been reading Western media for as long as I can remember — this has led me to care less about what other people think of me (in comparison with most Chinese people).

On lesbian dating, I think Chinese couples in general tend to take things quite quickly compared to the West. My first girlfriend of two years got my initials tattooed on her waist but is now married with a seven-year-old child. She told her husband, but I don’t know exactly what…or how he reacted. I’ve had a couple more relationships since then, but they didn’t work out.

I lead a super exciting life and get to spend all my income on myself (some of my friends spend up to 300,000 RMB [$42,000] per year on a single child). I even started a small reading group for some Chinese lesbian friends, which was fun. My story is positive — I get to express my sexuality and be exactly who I want to be.

L, 40, Gansu

The only way for the situation to change is if a significant figure in business or government (with money, influence, and respect) comes forward to challenge the government about its current LGBTI stance.

Growing up, we had no sex education at school, let alone information on homosexuality. It wasn’t until I started university, where I studied compound materials with the faculty of chemistry, that I learned what homosexuality actually was. Through the internet, I used sohu.com and tianyu.com to educate myself, share information and meet other lesbians, as well as learn more about my identity — yet [certain sites] have since been banned in China.

Initially, I was terrified of coming out to my family, and even now only they and my closest friends know. I am the youngest of four children; when I told my older sister, she broke down in tears simply because she wished I’d told her sooner. Holding such a monumental secret within me for over 25 years was unbearably painful, and something she only could have imagined.

I’m now 40 and live in Shanghai, where I work in marketing for the largest oil chemical factory in Shanghai. I’m leaving soon to launch my own startup. I have a girlfriend and have had relationships in the past, but I’m actually married to a (gay) man who lives with his partner — together they have two children. I had to get married, and my situation was convenient, but for many, marrying a straight man is the only option (yet I’d consider this too immoral).

In spite of the xinghun situation, technology has improved the atmosphere in China toward accepting and understanding one another, because there is more available information nowadays. For me, the hope for change came when watching If These Walls Could Talk starring Ellen Degeneres and Sharon Stone.

But to campaign in China, you need government permission, and said campaign can be no larger than 50 people — even on WeChat, groups are limited to 500 people. The only way for the situation to change is if a significant figure in business or government (with money, influence, and respect) comes forward to challenge the government about its current LGBTI stance. I think perhaps in 20 years we could see a change, but nothing will happen unless our voices are heard and acted upon.

To finish with a passage from The Dream of the Red Chamber, one of China’s the most famous novels:

“So who was she making the offering for?”

Parfumee’s eyes reddened slightly and she sighed.

“Oh, Nenuphar is crazy “

“Why?” said Baoyu. “What do you mean?”

“It was for Pivoine,” said Parfumee, “the girl in our troupe who died.”

“There’s nothing crazy about that,” said Baoyu, ”if they were friends. ”

“Friend,” said Parfumee, “They were more than that. It was Nenuphar’s soppy ideas that started it all. You see, Nenuphar is our Principal Boy and Pivoine always played opposite her as Principal Girl. They became so accustomed to acting the part of lovers on the stage, that gradually it came to seem real to them and Nenuphar began carrying on as if they were really lovers. When Pivoine died, Ninuphar cried herself into fits, and even now she still thinks about her. That’s why she makes offerings to her on feast-days. When Etamine took over the roles that Pivoine used to play, Nenuphar became just the same towards her. We even teased her about it: ‘Have you forgotten your old love then, now that you’ve got yourself a new one?’ But she said, ‘No, I haven’t forgotten. It’s like when a man loses his wife and remarries. He can still be faithful to the first wife, as long as he keeps her memory green.’ Did you ever hear Anything so soppy in your life?”

“Soppy” or whatever it was, there was a star in Baoyu’s own nature, which responded with a powerful mixture of emotions: pleasure, sorrow, and an unbounded admiration for the little actress.

This 66hands story is dedicated to the few Chinese girls and women who opened up to me about their stories — and to the many that are still unable to. Permission from each subject was granted for the publication of this article.

Q, 22, Fuzhou: “Love the girl inside you, she’s young and wild.”

J, 35, Shanghai: “You’re not alone in this; in the closet or not, it’s still a life well lived.”

L, 40, Gansu: “此路艰难,带足干粮 (cǐ lù jiānnán, dài zú gānliáng)… The road is tough, bring plenty of provisions.”