70 songs for 70 years of the People’s Republic of China

A song for each year of the People’s Republic of China: An attempt to distill the many diverse, fascinating currents of music in mainland China over the last 70 years into a primer.

This post originally appeared on Medium and is republished here, with edits, with the author’s permission.

A song for each year of the People’s Republic of China. This is an attempt to distill the many diverse, fascinating currents of music in mainland China over the last 70 years into a primer, an invitation to dig deeper.

From revolutionary operas and Western classical to rock ’n’ roll, disco, punk, and hip-hop, China blasted through 200 years of music history in just over half a century. In many ways, it offered a retelling of conventional musical wisdom. Of what music could be and do. That’s worth listening to.

Caveats:

1. These are not “70 Chinese songs” but rather 70+ songs that defined music in China in that year or since. They’re not necessarily the most popular, but tracks that captured alternative currents, emergent trends, and fissures in Chinese society.

2. There are obvious deficiencies in this list: regional canon, such as the music of Yunnan or northwest China, is not adequately represented. Some genres are missing, and other choices are weird, based on research and not emotional, lived experience. This can be fixed! If anyone has any critiques, suggestions, or questions, please let me know at @krishraghav on Twitter.

3. The Higher Brothers are missing from the list and that’s intentional. You can read Kiril Bolotnikov’s review of their latest album for a sense of why.

You can check out the entire list — artists and titles in list view — here.

Jump to decade: 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s

If you prefer to just listen to the songs, you’ll find this playlist on Spotify and YouTube.

Let’s roll.

1949: March of the Volunteers

China’s national anthem, briefly suspended when lyricist Tián Hàn 田汉 was imprisoned during the Cultural Revolution.

There’s also an American connection to the earliest rendition of this song, as David Bandurski writes over at Quartz in a story that sheds a lot of light on the anthem itself.

1950: Without the Communist Party, There is No New China

Jump to decade: 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | List View

Adapted from a 1943 chant in response to a Nationalist Party slogan (“Without the Kuomintang, there would be no China”), then modified by Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 in 1950, who added the word 新 (xīn) — “new” — before “China.”

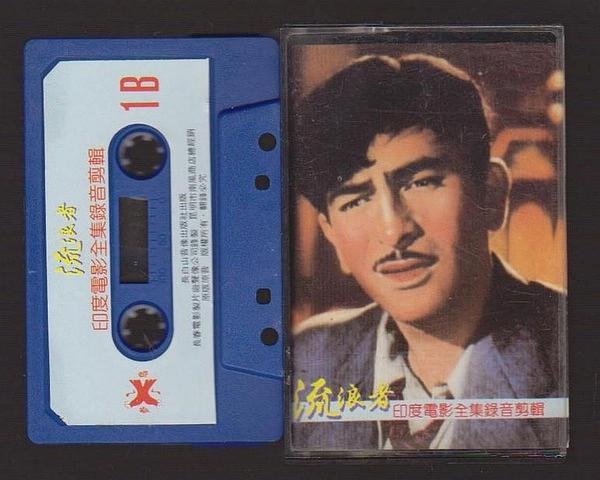

1951 — Awara Hoon

A small number of Hindi films, and a few from Pakistan, somehow made it into China in the early Communist era — and an entire generation can hum “Awara Hoon” to this day.

There’s a bigger story to be uncovered here. A small glimpse at the scale of this song’s popularity in China is seen in Vikram Seth’s From Heaven Lake, where the author charms a police chief into letting him travel into Tibet just by singing this song.

1952: Yellow River Cantata

Mao Yurun, formerly of the Shanghai Conservatory, has a fascinating paper on music under Mao and the works of Xiǎn Xīnghǎi 冼星海, the “People’s Composer,” in particular.

For more on the extraordinary story of Western classical in Maoist China, I’d recommend Jindong Cai and Sheila Melvin’s Rhapsody in Red.

1953: Meeting at the Fair

A recurring theme in the folksy red-adjacent songs of this time is the sheer diversity in setting and theme. As Julia Lovell has written in her (unmissable) new book Maoism: A Global History, a key objective at this time was to project the revolution as universal. The “frontiers’”of China were given special attention, with films and productions (like this one) set in…prairies! steppes! hills! islands!

1954: Shostakovich, Symphony No. 10

The Soviet influence on early Communist China was all-important. In 1954, the composer Lǐ Délún 李德伦 was sent to Moscow as one of thousands, to be trained at the Moscow Conservatory to build up China’s own classical institutions. The CCP’s political stance on this would shift sharply, soon, but Li in Moscow was in heaven, going to concerts, galleries, and museums.

He gets in a portentous statement after attending the premiere of Shostakovich’s 10th Symphony:

“I told [my professors] that this symphony had nothing to do with the modern USSR — it was so dark, and the USSR’s future was so bright!

“My teacher did not say anything.”

1955: Let Us Sway Twin Oars

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-q2mVfac1Oc

A song beloved by many post-’80s and post-’90s kids in China, featuring Beihai Lake in Beijing. Lyrics by Qiáo Yǔ 乔羽, music by Liú Chì 刘炽.

1956–1958: A Patriotic Triptych

A three-song triptych of the musical landscape in the mid-’50s as artists, musicians, and composers were tripped up in the cultural politics of the Anti-Rightists campaign. Patriotic songs in service of patriotic films, revolutionary songs in service of revolutionary films, and songs intended as public mantras to be chanted in the course of daily life.

1959: Butterfly Lovers

A fascinating work that came out of the beleaguered Shanghai Conservatory. Hé Zhànháo 何占豪 and Chén Gāng 陈钢 were both students who embarked on a bold attempt to “nationalize the violin” by adapting the tale often called “China’s Romeo and Juliet” to classical violin concerto. They adapted folk singing styles and Chinese instrumentation to the violin, creating a uniquely innovative fusion that even the People’s Daily hailed as “our own symphonic music.”

Then, their source material — decried as a “feudal tale” — was questioned and denounced, and the concerto fell into obscurity until it was resurrected after the Cultural Revolution.

1960: Five Golden Flowers

Jump to decade: 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | List View

Released right at the end of 1959, Five Golden Flowers is a fascinating full-color film set in a Bai minority 白族 commune in Dali, Yunnan. From my Kunming-based friend Ros: “It’s about a young Bai lad who searches for his love, but also interwoven with Bai custom is all this emergent Communist ethos — meeting coal quotas, discussing exploitation, etc. Sooooo interesting.”

1961: Song of the Women’s Detachment

Via Anthony Tao on this very site:

The movie (and subsequent ballet in 1964) was based on an all-female brigade in the southern island province of Hainan that operated against Nationalists in the 1920s and ’30s. It’s been said that the main character, Wu Qinghua, “reflect[s] the hostility and resentment of male-dominated society inherent in the ideology of the Communist revolution.” The song, like the movie, is a clarion call for revolution.

1962: Aye Mere Watan Ke Logon

Written just as the Sino-Indian war of 1962 was ending in a humiliating defeat for India, this tribute to the fallen soldiers of the war would, over time, become one of the most iconic Hindi songs ever sung.

1963–1968: The Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution was a tough time for original Chinese music. Jindong Cai’s Beethoven in China has a brutal, melancholy chapter on what became of the the country’s fledgling crop of idealistic composers and classical musicians.

The landscape was dominated by the “Eight Model Plays” (later 18), pre-approved productions that were repeated, adapted, and replayed all over the country. Mao Yurun has this incredible paragraph on how music creation was intended to work in this era:

We were instructed to obliterate all bourgeois sentiments and personal inclinations by embracing “group composition.” By this method, “the secretary of the party committee provided the theme, the masses provided ‘life experiences,’ and the composer-specialist provided the technique.” As the composer-specialist was undoubtedly an intellectual, an indispensable “persona non grata,” I would say he could only be entrusted with the least important assignment, technique. In this way we were supposed to be able to create something far greater than Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony! I was then working in the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra. I was ordered, together with some other performers, to write a “symphony” in a week’s time. (We needed to learn from the farmers and steel workers to do things quickly.) We took our baggage and bedding to the rehearsal hall. For five days and five nights we wrote the “symphony” without a wink of sleep using the assembly line method. We did accomplish our mission of writing a “symphony,” but somehow or other, it was never performed; understandably, it went into a wastebasket instead.

1969: The Yellow River Piano Concerto

Created when Jiǎng Qìng 蒋庆 (Madame Mao) was in absolute control of musical output in China, this was an adaptation of Xiǎn Xīnghǎi’s 冼星海 “Yellow River Cantata” by a group of Central Philharmonic composers, under Jiang’s guidance. The musicians were sent to live along the Yellow River for weeks — staying in caves, rowing with boatman, all to “conceptualize” a revolutionary symphony based on Mao’s idea of “people’s war.”

Pushed out relentlessly by the powers-that-be, it was a huge success, and the piece that introduced Western-style orchestral music to millions of Chinese.

It was rather infamously reviewed by the New York Times in 1973: “[It’s] movie music. A rehash of Rachmaninoff, Khachaturian, late romanticism, bastardized Chinese music and Warner Brothers climaxes.”

1970–1971: Frontier Music

Jump to decade: 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | List View

Two songs that symbolize the peak “expansive” period of Maoist rule, when the regime was gleefully exporting global revolution through training, arms, guidance, and foreign aid. Regions in the “frontier” were of special interest, and many flamboyant (and kooky) foreign insurgents passed in and out of Beijing’s Friendship Hotel. Everyone really should read Julia Lovell’s Maoism: A Global History.

1972: Home on the Range

An alarming amount of hand-wringing, rule-bending, and internal politics was necessary before the People’s Liberation Army Marching Band could practice the down-home American anthem “Home on the Range”:

They played it for a visiting Richard Nixon, and the details of that trip are an extremely entertaining read.

1975: Sam Hui and Cantopop

The song that launched a Cantopop tidal wave, one that would crash China’s shores in less than a decade. Sam Hui’s (许冠杰 Xǔ Guānjié) theme song for Games Gamblers Play, a martial arts comedy, set the template for pop songs that reached a mass audience and its unique hybrid sound (Hui was a mainstay in the ’60s rock ’n’ roll boom in Hong Kong) created a thousand imitators.

1976: Richard Clayderman

The pianist Richard Clayderman has a strong claim to being the most popular musician in China, a claim he’s milked fairly well with repeated tours, collaborations, and guest appearances on Chinese state TV. But his No. 1 China claim-to-fame dates back to the late ’70s, when he composed the song that would become China Mobile’s default call-back tone.

1977: Teresa Teng, The Moon Represents My Heart

An eternal classic. Teresa Teng’s (邓丽君 Dèng Lìjūn) story is stuff of legend, and her hold on mainland Chinese imagination was so strong in the late 70s that she was both “spiritual pollution” and on par in stature with paramount leader Deng Xiaoping.

1978: Descendants of the Dragon

There’s a book waiting to be written about this song by Hóu Déjiàn 侯德健, who has gone from Tiananmen protester to patriotic composer.

“Descendants of the Dragon” was written as a nationalistic anthem for Taiwan, popularized as a pan-Chinese call for unification, recast (by the lyricist) as an anthem in support of the students at Tiananmen Square, and then subsequently used by both mainland and Taiwan broadcasters as a “patriotic” song. In a final plot twist, it’s also been re-released as a paean to the experiences of Chinese immigrants to the U.S.

1979: Hey Jude (cover)

Audio unavailable

China’s oldest known “rock band” — four university kids in Beijing who played covers of the Beatles, Bee Gees, and Paul Simon. Not much else is known about them, no audio or video survives, but they set the stage for a lot of magic to come.

1980: Night at a Naval Base

Jump to decade: 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | List View

The beginning of the ’80s was a strange transitional period in music. China was “opening up,” yes, but decades of knee-jerk Maoist responses are hard to undo, leading to situations such as the drama around “Night at a Naval Base.”

From Jonathan Campbell’s Red Rock:

1981: Jean Michel Jarre

I’m not sure why (or how) Jean Michel Jarre became the first major Western pop artist to play live in post-Cultural Revolution China. But it produced some of my favorite gig posters of all time:

1982: Peng Liyuan, China’s First Lady

One of the songs on which China’s First Lady built her fame. Two brave people on Xiami have rated it 1 star.

One of the recurring themes of the ’80s is the “gala song” — the assured fame that follows a successful appearance on the annual CCTV Spring Festival Gala. Péng Lìyuàn 彭丽媛 rode that wave early, becoming a household name by the mid-’80s. Many of the singers of this era would also remain enduringly popular in the diaspora.

1983: Leslie Cheung

Teen heartthrob-turned-acclaimed-actor Leslie Cheung (张国荣 Zhāng Guóróng) was emblematic of the “港台” (Gǎng Tái — “Hong Kong and Taiwan”) era when everything Hong Kong was “cool” — the city a utopia of gilded dreams and untold riches.

1984: My Chinese Heart

Cheung Ming-man (张明敏 Zhāng Míngmǐn) was the first Hongkonger to sing at the CCTV Spring Festival Gala. It was a political risk, one that paid off handsomely when his performance, a swooning patriotic ballad, made him a local superstar and the song the unofficial anthem of the diaspora.

1985: Wham!

I have three favorite things about Wham!’s bizzaro China tour.

1. The reason it happened. From the BBC:

In 1985, China was just opening up to the outside world following the tumultuous Cultural Revolution.

At the same time, Wham! were eager to prove that they were the world’s biggest pop band. A concert in China was just the ticket.

The duo’s manager, Simon Napier-Bell, tried to convince various Chinese officials over lunch that the concert tour was a good idea.

His successful sales pitch hinged on how China would appear to the outside world if George Michael and Andrew Ridgeley were allowed to play. Wham!’s presence would be proof, Mr Napier-Bell reasoned, of the Communist Party’s desire to welcome foreigners, and much-needed foreign investment.

The pitch worked…

2. In the opening act, singer Chéng Fāngyuán 成方圆 appears to have played Chinese-language covers of Wham! hits, albeit with soaring socialist lyrics:

Wake me up before you go go.

Compete with the sky to go high, high.

Wake me up before you go go

Men fight to be first to reach the peak

Wake me up before you go go

Women are on the same journey and will not fall behind.

3. The official show merch:

1986: Cui Jian, Nothing to My Name

A staggering, monumental song by the godfather of Chinese rock, Cuī Jiàn 崔健.

There’s a tendency to place “Nothing to My Name” as the single-point origin of all Chinese alternative music. Jonathan Campbell wrote an entire book on this premise. There is an anthemic weight attached to this song that, to me, distracts from just how poignantly personal it is. It’s a shapeshifter, a sonic blast of yearning that has prophetically soundtracked so many tragedies — 1989, the Sichuan Earthquake — imbuing them with a glimmer of hope.

My favorite thing about the song is the fact that the “guitar solo” is actually played on the suona, a pleasingly loud Chinese reeded flute. It just works so well with distorted guitars — a tactic future bands like Jiajiatiao would use to great effect.

1987: A Fire in Winter

If I had to choose, this would be my No. 1 song on the entire list. Fèi Xiáng 费翔 burnt his entire career in Taiwan for the chance to be on the CCTV Spring Festival Gala — and he’s got no choice but to turn it up to 11. This is the most fun the Gala has been in 32 years. [Editor’s note: It was also good two years later.]

Zang Tianshuo: 朋友 (péngyǒu — “Friend”)

R.I.P Zāng Tiānshuò 臧天朔. As proto-rockers go, he was the OG legend, and “Peng You” is his most potent contribution to Chinese rock canon.

1988: My Future is Not a Dream

Zhāng Yǔshēng 张雨生 is a Taiwanese Mandopop legend who died tragically young but blazed a trail of ultra-mega-hits in his all-too-brief career.

1989: For Freedom

This extraordinary song was part of a May 1989 solidarity fundraiser in Hong Kong, standing with the student protesters then occupying Tiananmen Square. Teresa Teng, Hou Dejian, Cheung Mingman (张明敏 Zhāng Míngmǐn) were all part of it, as was the band Beyond.

The group’s representative then flew to Beijing, where he was detained at the airport. The funds raised, over a million HKD, were confiscated and disappeared.

1990: Kenny G, Going Home

Jump to decade: 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | List View

Kenny G’s “Going Home” is as Chinese as Lanzhou hand-pulled noodles — a continuous, unavoidable, pervasive part of the urban fabric. Malls will play it at closing times. Elevators will blast it at odd hours. It’ll waft from public speakers and PA systems in schools when classes are over. Five hundred million people have been conditioned to “go home” with the simple three-note melody of this song. It is, without a doubt, one of the most recognizable pieces of music in China.

Kenny moves people here in a way that’s hard to describe. But why describe when I can show you the greatest Kenny G video of all time, recorded at one of his China gigs. I’ve been sitting on this for years:

1991 — Pearl of the Orient

Kimberly Jin in The China Project:

In 1986, Lo Ta-yu (罗大佑 Luō Dàyòu), a Taiwanese singer-songwriter and a cultural icon in Mandopop, went to Hong Kong and wrote a song called “Pearl of the Orient,” Hong Kong’s nickname. In the lyrics, he called Hong Kong his lover and admired the city’s splendor and “romantic demeanor.” More importantly, he sympathized with the city’s suffering under colonial rule and traced its cultural roots to China.

It’s a complicated song. Lo is holding ambiguous ideas of nation and culture in tension, but that ambiguity is dangerously fragile.

In the process of “termination” and “return,” the vast majority of Hong Kong people lost their grip on political decisions. Nor were they certain of their personal future. “History” failed to bring hope to this city; instead, it pushed it towards the nostalgia of the past. Three decades later, Lo’s “Pearl of the Orient” still resonates with many Hong Kongers questioning the city’s future.

1992: Glam rock hair metal!

Tang Dynasty, A Dream Return to Tang Dynasty

Black Panther, Don’t Break My Heart

Hair metal glam rock excess in early-’90s China. A lot has been written about them pretty much everywhere. Jonathan Campbell’s Red Rock is a good place to start.

1993: Beyond

Hong Kong band formed in 1983. “Boundless Oceans, Vast Skies” (海阔天空 hǎi kuò tiān kōng) was recorded in 1993, the same year that lead singer Wong Ka Kui (黄家驹 Huáng Jiājū) died on the set of a Japanese game show when he fell off a three-meter platform.

1994: Dòu Wéi 窦唯, Be Good, Boy; Zhāng Chǔ 窦唯, The Ant

“Husband of famous singer Faye Wong gleefully dabbles in works of music.”

What if I told you that Zhang Chu’s ‘The Ant” was Part 2 of an epic musical trilogy adventure that spanned four continents and six decades? It’s true! You can read about it here.

1995: Campus Folk Movement

In 1976, a young Taiwanese musician named Lee Shuang-tze (李双泽 Lǐ Shuāngzé) stormed a stage at a folk music festival in Taiwan’s Tamkang University, shouting, “We should sing our own songs!”

Then he smashed a Coke bottle and decried the excessive Western influence on local music. This, the Tamkang Incident (淡江事件 Dànjiāng shìjiàn), led to the Campus Folk Movement (校园歌运动 xiàoyuán gē yùndòng) that would produce startling, simple songs with a wounded heart and nostalgic mood.

Mainland China’s campus folk movement only took root 20 years later, but singers like Lǎo Láng 老狼 (featured above with the song “You, My Deskmate” [同桌的你 tóng zhuō de nǐ]) and Gāo Xiǎosōng 高晓松 seemed to channel that same spirit, albeit with traumas that were larger and more immediate.

The writer Madeleine O’Dea refers to a “wounded romantic spirit” that took root in artists in this post-Tiananmen era. In her book The Phoenix Years:

Ömärjan Alim, Mehman Bashlidim (I Brought Home a Guest)

Audio Unavailable

In 1995, the seminal Uyghur poet Abdurehim Ötkur died in Ürümchi in the far west province of Xinjiang. His funeral was an emotional affair — his novels and poetry were widely read and beloved, serving as powerful reminders of the “unfinished journey” of the Uyghur people to claim their identity and dignity.

A number of musicians put out cassettes in tribute. They spread widely, quickly — Urumqi’s bazaar networks had developed a vibrant trade in cassette tapes, and one stood out at this time: Ömärjan Alim. The ethnomusicologist Rachel Harris writes:

Alongside the titular poem by Ötkur, it included many other politically resonant songs written by contemporary Uyghur poets. These songs took the standard state narrative of China’s “big family of friendly nationalities,” and recast the relationship between Han Chinese and Uyghurs as that of colonizer to colonized (Smith 2007). They also offered a stringent critique of contemporary Uyghur society and culture. The lyrics sung by Ömärjan Alim lamented the Uyghur national character as they sang it into being — it was a character marked by passivity, opportunism, decadence, and disunity.

This song, in particular, anticipates some of the tensions underlying burgeoning Han migration to the region, likening, as Harris puts it, “the tradition of hospitality — a founding principle of the Uyghur national character — to gullibility.”

I invited a guest into my home

Asked him to sit on a soft cushion

And now I can’t get in

To the home I built myself

1996: A Story of Spring

“A Story of Spring” offers an interesting counterpoint to songs from the revolutionary era. It’s a song about the end of Mao’s personality cult and yet ends up, ultimately, becoming a paean to another personality — Deng Xiaoping. From China Media Project:

These are lyrics penned by an ordinary man moved by Deng Xiaoping and the reform movement he represented. But the song gained in popularity only after 1996, as Deng Xiaoping fell gravely ill. It is perhaps impossible to know whether the paramount leader ever even heard “A Story of Spring” before he passed away in February 1997.

1997: Tengger, Heaven

I love Tengger (腾格尔 Ténggé’ěr). He was among the earliest breakout stars from the Mongolian musical traditions, seeding the sounds and timbre of the region to a prime-time audience before bands like Hanggai and Huun Huur Tu took it global.

Tengger was also among the few popular post-Mao non-Han musicians who resisted drawing on some idealized vision of their “traditional culture,” and attempted to build a musical identity beyond being spokespeople for their roots:

I can’t sing anymore the kind of songs that deceive oneself as well as others, like “The Beautiful Grassland Is My Home.” My elders and my fellow people will not forgive…In my native land, Ordos grassland, the herding people live year after year in drought and poverty. The lushness of the grassland belongs only to the past.

1998: SMZB and Wuhan Punk

Wuhan punk rock represent!

Formed in 1996 and fronted by the amazing Wú Wéi 吴维, SMZB are punk pioneers. Sharp, uncompromising, staunchly DIY — they gave Wuhan its “punk rock” branding that’s stood proudly for two decades. For more on Wuhan, get this issue of Maximum Rock & Roll, which includes an annotated discography and a scene report from the city!

Early 1999: Dakou and Boredom

There are two overlapping trends to unpack here.

One was dǎkǒu 打口, referring to hundreds of thousands of unsold cassette tapes and CD stock that was dumped in China. As the throwback expat magazine Beijing Scene describes it:

Da kou is the Chinese term for catalog cut-out CDs and cassettes that have been gashed with a saw to prevent resale. Record companies in the West can save money by destroying surplus stock, but the law only requires that a small gash be sawed into the disk or cassette (and packaging), which renders the product “destroyed,” in a legal sense. The music is still listenable: sawn cassettes are easy to repair, and on CDs the gash only ruins the last song or two of an average-length LP.

These made their way in unsorted piles to streetside shops all over China, leading to an entire generation discovering, almost at random, everything from Madonna and Bob Marley to Morrissey and Sonic Youth. Jeroen De Kloet’s book, China With a Cut, is a great place to learn more.

The second trend was boredom. The idleness of China’s so-called “wasted youth,” kids who’d dropped out or were asked to drop out of the narrow path to money and success, led to a very particular kind of ferment — in art, in music, in writing. Beijing’s punk scene, especially the cluster of bands that formed around Scream Club in Haidian, were of this ilk, and Wuliao JunDui (The Bored Contingent) laid the foundations for an entire country’s punk underground out of sheer boredom. The always brilliant Nathanel Amar has an essay on them here.

Mid-1999: The Flowers

If you were a teenager in 1999, The Flowers (花儿乐队 huā’er yuèduì) was the band that made you want to pick up a guitar and shred. The song above is “Stillness” (静止 jìngzhǐ).

Late 1999: New Boy

The Beijing-based label Taihe Rye Music was signing up some of China’s most interesting artists in the late 1990s, Pǔ Shù 朴树 among them. His debut album, I Want to Go to the Year 2000, was a runaway success, selling over 300,000 legal copies and around a gazillion pirated ones. From Shanghai-based Finn Yan:

This album really represents that generation…the world was changing too fast in front of our eyes: the Internet, a whole new century, all kinds of new things flooding in. Pu Shu captured that rush — both our wide-eyed curiosity and our naive simplicity.

Fun fact: The song 冲出你的窗口 (chōng chū nǐ de chuāngkǒu — “rushing out your window”) from this album was used to promote Microsoft’s Windows XP in China.

2000: Faye Wong

Jump to decade: 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | List View

Wong Faye (王菲 Wáng Fēi).

Her impact, her reach, her stature. It’s impossible to reduce it to a song. Or even an album. This, her 17th studio album, is not her most popular or influential. But it captures what made her so fascinating.

The first five songs are explorations of Buddhist themes, with complex songwriting that seems to channel someone like Bjork. Then come the radio-friendly unit-shifters, followed by two songs that somehow meld these two strands together. It’s Wong Faye at her most experimental, before her divisive 18th album and a long hiatus.

2001: Jay Chou

Jiayun Feng in The China Project:

This was the first Jay Chou song I ever heard, and I found it irritatingly jarring at the time. Who’s this average-looking boy sing-talking about his fondness for nunchucks, and doesn’t he know what a proper song should sound like? What I would soon learn was: No, Chou was not here to play by the rules. He’s a straight-up music genius who for a long time stayed ahead of the curve by writing songs like this, which, given a second chance, I’ve found to be insanely catchy.

Jay Chou (周杰伦 Zhōu Jiélún) is a sensation. The biggest Mandopop star of the 21st century. Even in 2019, a new Jay Chou song breaks streaming records and brings websites down.

2002: Xǔ Wēi 许巍, Blue Lotus (蓝莲花 lán liánhuā)

Hey, it was super popular and won every award!

2003: Hang on the Box

Twenty years ago, Wáng Yuè 王悦, Yilinna 隐退 (Yǐntuì), and Yáng Fān 扬帆 of the band Hang on the Box made the Beijing punk scene an international topic, posing in Tiananmen Square for a February 1999 cover of American magazine Newsweek. Crouched under the headline “China: The Limits on Freedom,” the three teenagers were put forward as bold iconoclasts, the new face of alternative Chinese youth.

They quickly became an international sensation, signing with a Japanese record label and becoming one of the first Chinese bands to perform at the South by Southwest music festival in Austin, Texas. Their original members — singer Wang Yue, better known as Gia; Yang Fan, who started on drums and later moved to guitar; Yilinna, the band’s original bassist; and Shén Jìng 沈静, who replaced Yang Fan on drums in 1999 — all remain active musicians and cultural influencers.

The writer Josh Feola and I drew a whole comic about the story of “Hang on the Box.” You can read that right here.

2004: Joyside

This boozy, sloppy drunk-punk band built a cult following in the early 2000s and then pulled China’s first LCD Soundsystem-style “reunion tour.” Joyside (and later Carsick Cars) precipitated the indie rock scene in Beijing around the venue D-22 — a scene that is both rightly hailed and over-covered by international media.

Torturing Nurse, JUNKYISUZU

A household name in harsh noise circles around the world, Torturing Nurse has gone through many lineup changes in its lifespan to date, but it has since 2015 been the solo project of original co-founder Cao Junjun, better known as Junky. Cao got his start as a musician playing drums in Junkyard, a near-mythical Shanghai band that formed in 2001 and managed to fire off one album, Junk & Retain Junk, before its members split off in different directions. Very different directions. Two of Junkyard’s members, B6 and Ma Haiping (aka MHP), have gone on to become two of Shanghai’s most polished, accomplished electronic music producers. Junky, on the other hand, “wanted to make something more extreme.”

It’s fair to say that Torturing Nurse is the most extreme band in China, with performances that have included bondage, S&M, and varying grades of violence. It may be hard to understand the point of Harsh Noise, but think of it as elemental particles…experiments by groups like Torturing Nurse form the primordial soup of sound from which more…palatable bands draw.

2005: The Pig Song

Dan Rothwell, writing in a Friday Song for The China Project, on China’s first “viral” star:

The year’s 2005, and according to Internet Live Chart, only 8.5% of the population in China has access to the internet at home, connected via “any device type and connection.” One of the 8.5%, Wáng Jǐnméi 王瑾玫, decided to hook up a headset to a computer, don the moniker Xiāng Xiāng 香香 (literally, “fragrant fragrant”), and record a song about a pig in the hope of getting signed.

It worked.

Knowing that intellectual property rights weren’t necessarily at the top of the e-pirates’ priorities, putting the track online for free soon lead to more than 1 billion downloads, a record deal generating over 40 million RMB ($6 million) in record sales, and being forever known as China’s first internet pop icon.

FM3, Buddha Machine

“Calm on the Box”?

FM3 pulled off a minor miracle with its Buddha Machine, a little plastic box that blasted snatches of drone and ambient music recorded around Beijing. It got the attention of Brian Eno, Throbbing Gristle, and Talking Heads’ David Byrne (he called it “the future of music,” which…come on, dude).

The members of FM3, like many musicians in China, were masters of adaptation. They were making electronic music before alternative nightclubs, in the height of the SARS epidemic, under a curfew. The Buddha Machine was their clever chabuduo hack, a little piece of magic that punched above its weight — much like FM3 themselves.

2006: Khalil Fong

A thoughtful, multilingual pop star who fused Mandopop with soul and R&B, and embraced a more DIY approach to pop production. Khalil (方大同 Fāng Dàtóng) is a treasure, and this song was his breakout smash hit.

New Pants (新裤子 xīn kùzi), Bye Bye Disco

An enduring indie hit. The “Shins, New Slang” of Chinese music. (Sorry.)

2007: Carsick Cars

The word “scene” is overused in China (I’m guilty as charged).

If you really dig into it, very few clusters of bands in China became a “scene” — which I loosely define as a self-contained bubble of music, ideas, fashion, writing, and film that bounced off individual members and was rooted in a particular place and time.

While acknowledging that it was perhaps a bit too courting of media attention, the music that came out of D-22 (a tiny dive bar in Beijing) was one of China’s few halcyon “scenes.” These kids sparked a small revolution in pre-Olympics Beijing and captured a time — and a mood — that has not been replicated since. Just those five years (2007–2012) produced so many colliding ideas across mediums. It was heady, it was charged, it was special.

Here’s a photo of Carsick Cars by Rèn Háng 任航 (RIP):

Zuriaake, God of Scotch Mist

Zuriaake invented Chinese black metal. They are a spectacular live act, wearing costumes meant to evoke distant figures in old Chinese landscape paintings.

From an interview with core members Bloodfire and Bloodsea by the AFP:

“If you’ve understood the essence of a Western genre and are still just imitating the form, you’ll slowly become mediocre. We’re playing pure Western metal, but we’re unique,” said Bloodfire, refusing to give his real name.

In China, horror is “more subtle and veiled, about the unknown” rather than gore, he explained. “I want to express Chinese-style horror, and ancient Chinese-style withdrawal from society, nobility and virtue,” he said.

To do that, the band turned to the chaotic Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods from around 771 to 221BC for inspiration – the last time they felt Chinese literature held an emotional intensity and despair that paired well with the black metal aesthetic.

“From that time on, Chinese poetry became more and more formalised, and became increasingly sunny – it lacked darkness,” Bloodfire said. The band’s music, he said, tries to convey the feelings of bygone Chinese literati who sought to “live in seclusion and not involve themselves in worldly affairs, despite having a clear picture of the world and its problems.”

The idea that 2,000 years of Chinese history has been discarded for not being “metal” enough is a thought that gives me joy on dark days.

2008: Yin San’r, i.e., IN3

From Jeremy Goldkorn in The China Project:

Yin San’r formed in 2007 in Beijing and have released a bunch of songs online. Their rhymes are sung in dirty, Beijing- accented Chinese. They rap about hypocrisies and daily injustices in society, and sometimes they just like to let loose a volley of curse words. In 2015, they were blacklisted by the Ministry of Culture for vulgarity, and their songs were removed from online stores and music platforms.

“Beijing Evening News” (a local tabloid) is about the gap between what you can read in the newspaper and what is really going on in society. About how so much of what goes on in Beijing is “hanging up a sheep head but selling dog meat” (挂羊头卖狗肉) — trickery, deception, and passing off dodgy dealings as honest business.

The song is also about feeling alienated in Beijing. And how when you live in Beijing, sometimes a familiar smell or a sound — like the newspaper vendor calling out “Beijing Wanbao” — suddenly makes you feel at home.

2009: Chris Lee

Chris Lee (李宇春 Lǐ Yǔchūn) was a new kind of pop star. She won a reality TV show, charming both the judges and the crowd with her spiky, androgynous look and non-traditional fashion (“loose jeans and button-down shirts, with no make-up”).

She exists now in the strange liminal space afforded to the upper echelon of pop stars in China — transcending her music to be a style icon and ambassador for a dizzying number of brands and organizations.

This shamelessly confident ripoff of MIKA’s “Lollipop” was one of Chris Lee’s earliest calling cards — her annual concert tours are still called “Why Me.”

Shānrén 山人, 30 Years

Shanren began as an indie rock band that channeled folk songs from the traditions of the Yi ethnic minority of Yunnan. Their popularity made them shift gears, expanding their vision to represent a much larger set of music from the region. They spent years living with and learning from the Nu and the Wa in rural Yunnan. They were now a self-described “agricultural rock band,” championing the rural masses and critiquing excessive urbanization.

Xiaorong Yuan in his thesis on Shanren and “authenticity”:

Although Shanren shies away from political metaphor, the portrayal of the reality of living in Beijing reflects fundamental issues that have occurred during the Reform and Opening period (1980s to present). For example, their song “Thirty Years,” reflects the challenges rural people face living in large urban areas during this period. Instead of singing about how happy they are about the economic development of China, like mainstream media’s minority songs, they express doubt and mock themselves throughout their songs, as well as reveal an intense desire to be honest with themselves.

2010: Omnipotent Youth Society

Jump to decade: 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | List View

There has never been a more majestic album of indie music in China.

Shijiazhuang’s Omnipotent Youth Society made a document of everyday joys, surreal humor, and dark underbellies — bright brass tempered by crunchy guitars over earthy vocals. It was so good that the band hasn’t written a single thing since, and continue to play the same nine songs to huge audiences that haven’t tired of them one bit.

Hua Lun, Shanghai Tourists

There was always something perfect about the popularity of “post-rock” in China — a genre of cyclical booms and busts, temperamental sentimentality and the conjuring of dread, existential malaise and desolate beauty.

Bands like Huā Lùn and Dalian’s Wǎng Wén 惘闻 owned the genre, finding reserves of energy and innovation long after the rest of the world had discarded the sound. Hua Lun, in particular, were masters of mood with uneven pacing — this 2010 album is like an old Jiǎ Zhāngkē 贾樟柯 film in audio form.

Hua Lun went on to write the score for An Elephant Sitting Still, a bleak film underscored by tragedy: director Hú Bō 胡波 committed suicide soon after finishing the film, age 29. As tribute, as elegy, as memory, as grief: Hua Lun and Chinese post-rock are a vital counterpoint to China’s syrupy pop positivity.

2011: Escape Plan

Escape Plan represents a dream. A trajectory of fame unique to music in China.

I first saw Escape Plan play its Coldplay-esque Britpop at Beijing’s old Mao Livehouse in 2011 to a crowd of roughly 100 people. They were already five years old at this point, having just changed their name from “Perdel.”

By 2014, they were on primetime TV, buoyed by the huge success of their single “The Brightest Star in the Sky” (夜空中最亮的星 yèkōng zhōng zuì liàng de xīng). They were well-suited to mainstream attention — headlining festivals, playing commercial opportunities, signing deals, dropping in on reality TV shows.

In 2019, they were on the CCTV Spring Festival Gala.

Whatever your opinion of their music, the existence of this ladder — from dive bars to the biggest stage in China — built purely on music and nothing else, is worth celebrating, even as it appears that it’s been kicked down.

2012: Hedgehog

The Little Big Band that could.

Hedgehog was the underdog football team. The one that made it despite the odds. For fans who’ve stuck with them since the early days, we’ve seen it all. Glorious, transcendent shows. Shitty, nightmare shows. Amazing albums. Meh albums. The good times and the bad. A long hiatus, kids and families. And finally, a…reality TV show triumph that ultimately sealed its legacy?

China’s weird. But if it means more Hedgehog for everyone, we’ll take it.

2013: Duck Fight Goose

Sinofuturism now!

Duck Fight Goose is a great example of how elemental particles (like Torturing Nurse and other painfully abstract music) produce, down the line, works of extraordinary clarity and immediate relevance.

Also, its bassist 33EMYBW is going to be a future star.

2014: EXO-M

Where would China’s music be without Lùhán 鹿晗 and Kris Wu (吴亦凡 Wú Yìfán)?

It would…probably be exactly in the same place musically.

But the aesthetics of pop music in China was changed forever with the ascent of Luhan, Kris Wu, and others collectively referred to as 小鲜肉 (xiǎo xiānròu), or “little fresh meats.” Their immaculate grooming and androgynous looks sit at an odd intersection between legions of adoring fans and a growing displeasure from China’s culture barons at their perceived “sissiness” and “lack of masculinity.”

Lauren Teixeira in Foreign Policy:

For party elders raised on an ideology of hardness and struggle, the growing influence of xiao xian rou is hard to accept, especially as the military steps up recruitment with increasingly macho propaganda aimed at young men. But while young men are the future of China’s military, young women play an increasingly important role in maintaining the country’s economic might — and soft boys are part of the deal.

2015: Social Shake

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1jrWQ0PpuXs

From Tianyu Fang in The China Project:

Remember when the world was obsessed with Psy’s K-pop single Gangnam Style, which spread like a virus? Young people in China, especially in rural areas, are having a similar craze with the shehui 社会 subculture, translated literally as “society,” referring to a type of rough-and-tumble street culture.

Xiāo Quán’s 萧全 2015 song worked like a “greatest hits” version of different “social shake” dances, a symbol of the “shehui” lifestyle. Needless to say, it went very viral, and is a good example of the modus operandi that drives China’s social media fame economy.

Wutiaoren, Canton Girl

Sometimes you need the grandiose. And sometimes you need the intimate.

Wǔtiáorén 五条人 is the latter — just lovely, understated, heartfelt songs about everyday concerns and daily observations, sung in a lilting regional Haifeng dialect. Guangdong has an entire trajectory of alternative music parallel from the rest of China, and whatever strands collided to produce Wutiaoren: thank you.

2016: No Party for Cao Dong

The band that gives this music industry hope.

Taipei’s No Party for Cao Dong is massive in China — it went from small shows in dive bars to filling out stadiums. You can find its songs in KTV booths nationwide.

But fame hasn’t diluted the band one single bit. Still as loud, harsh, uncompromising, intelligent, and emotionally resonant as ever, this is that rarest of bands that is universally acclaimed for no reason other than the force of its songwriting.

Hyph11e, Leaf

Shanghai, for a while, was one of Asia’s club capitals.

It hosted new sounds (like South African Gqom) long before many other cities in the region did. Its spiderweb of small labels and collectives forged cross-continent friendships and collaborations with fellow up-and-comers in clubs around the world. It began to generate its own, unmistakable sound.

Hyph11e (a.k.a., Tess) was the co-founder of one of those collectives, the fashion-forward Genome 6.66 Mbp. Her breakneck beats, propulsive start-stop rhythms, and chitinous artwork were a perfect storm — the entire scene, defined, in one single song: her 2016 single 叶子 (Leaf).

2017: Atilar

Abdurehim Heyit: the Uyghur Bob Dylan.

Heyit, born in Kashgar in 1964, was a virtuoso composer whose versions of old Uyghur folk songs were so beloved that bootleg cassettes far outstripped official supply. He was a sensation on the long-necked dutar lute, and an icon of the Uyghur nation.

He radiated a cocky boldness (even his dutar was bigger than anyone else’s), far removed from the Chinese state’s preferred image of ethnic minorities as smiling, welcoming hosts to their Han “big brothers.” Like Dylan and New York in the 1960s and ’70s, Heyit’s life in song was part of a mosaic of pop, folk, and underground music in Xinjiang.

But that changed after the summer of 2009, when interethnic tensions exploded into riots that left at least 200 dead in Urumchi. Over the next few years, an intense security crackdown straitjacketed the region, resulting in a widespread cultural freeze and, by 2017, detentions of an estimated one million mostly Muslim ethnic minorities — many of them Uyghurs — in a vast network of “re-education” camps.

Heyit was arrested in 2017, too, and disappeared from public view. Some sources say it was because of a performance of this song — “Fathers.”

His music, even in captivity, would have a strange and powerful calling. In February 2019, rumors of his death swirled in nearby Turkey, where his music is beloved, forcing the Chinese government to release a video claiming to show Heyit in good health. But shaved of his trademark mustache and boundless confidence, the star that Uyghurs had known was gone.

The video sparked a furious and spontaneous social media movement. Activists and ordinary Uyghurs took to Twitter and Facebook using the hashtag #MeTooUyghur to ask for proof that their loved ones, too, were still alive.

Heyit’s current status is unknown, and his music now soundtracks a landscape of grief and loss.

David Boring, I Can’t

David Boring’s debut album was a crystal ball. A jagged, sharp, screeching work of Hong Kong ennui and Hong Kong anger.

Everything is beautiful and everywhere hurts.

Everyone’s a victim.

Everything is boring.

Their world — withdrawn, alienating, gloriously noisy — was a “self-indulgent celebration of new age sufferings.” It was a mood board for the frustration and anger of the post-Occupy years. Their anger then is the anger we see now on the streets of Hong Kong — a grief and rage, considered and thoughtful and impatient and untamed.

They’re my absolute favorite band in the world right now.

2018: Lexie Liu

The Higher Brothers are canceled.

Lexie Liu, the multi-incarnate cyberpunk hip-hopstress, is the Chinese rap artist that I think defines the current wave. There’s pride and uncertainty in her songs, there’s defiance and acceptance, and there’s vision…a thousand ideas on where Chinese hip-hop could go. “Nada,” from 2018, seems to draw on at least 10 artists in this list — Duck Fight Goose chief among them — and its sense of lineage combined with a relentless striving toward the future is what I find exciting about Lexie.

She’s called Chinese hip-hop a “sausage party” and wants to break that. She finds macho swagger unsettling, and wants to bring more introspection into the genre. Plus she’s signed to 88Rising, a phenomenon in pan-Asian if there ever was one.

Lexie Liu > Higher Brothers. @ me all you want.

2019: Glory to Hong Kong

An anthem written by Hongkongers for Hong Kong, “Glory to Hong” (願榮光歸香港 yuàn róngguāng guī xiānggǎng), originally released on August 31, has become the anthem of the Hong Kong protests.

CrimethInc. on the last three months in the beleaguered city:

For others, the imagined catastrophe is seen as a means by which to restore Hong Kong’s rightful place among the foremost cities of the world, something that is indicated in the most popular slogan of the struggle: “Restore Hong Kong to glory, revolution of our times.” The “glory” referenced in the slogan is a fantasy of prelapsarian purity—the Hong Kong of hard work, the individual initiative of the honest, entrepreneurial common man, whose life is unsullied by the machinations of big politics.

While it’s fine to hypothesize about a situation of common ruin, why can’t we also think about how to create the material basis for everyone to thrive and flourish together? And what could this “together” mean, who does it encompass, when everyone we customarily exclude from the picture—ethnic minorities and their second-generation offspring, domestic migrant workers, new migrants from China, and mainlanders who await the right of abode—is implicated in the future of the city? Why do we believe that these questions should be deferred until a government is elected to address them, when there are so many instances of autonomy in this struggle that could serve as premises upon which to develop these conversations right now?

That’s it! Thanks for reading. I hope you discovered something cool.

I’d love to hear critique, feedback, and suggestions. I’m @krishraghav on Twitter, or krish DOT raghav at the Google mails.

If you liked this project, do check out my forthcoming comic book history of the Beijing music underground!