‘Song at Midnight’: China’s brilliant take on Phantom of the Opera

We’re commencing the countdown to Halloween with a series of film columns about Chinese horror flicks. This week: Song at Midnight, the father of Chinese horror cinema, based off Phantom of the Opera. Despite frequent remakes, it is the original that remains the most eerie, heartwrenching, and stellar.

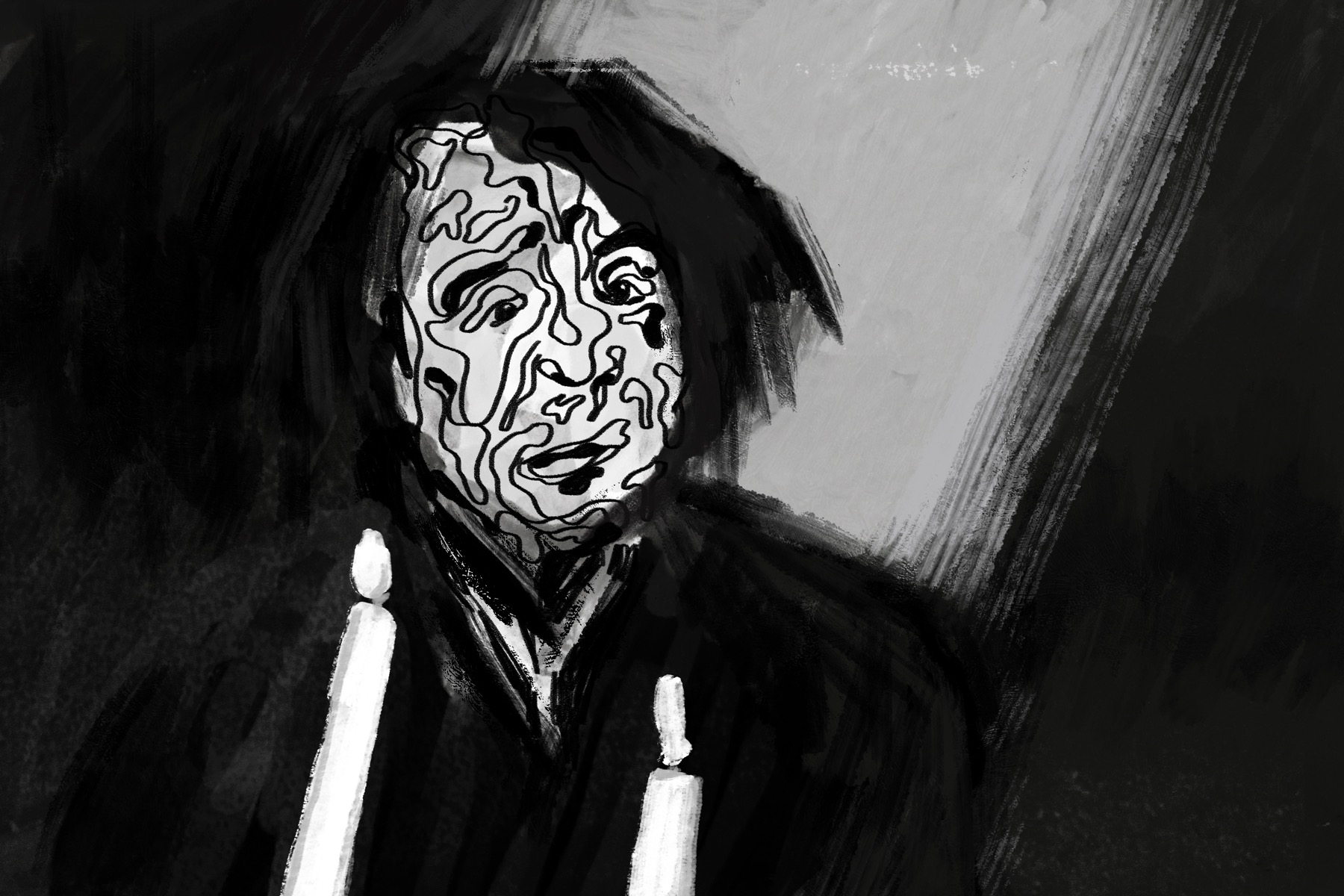

Image by Anna Vignet

In February 1937, filmgoers and passerby in Shanghai were shocked and intrigued by a strange poster outside the gate of the city’s popular Jincheng Theater. The picture, an advertisement for a new movie called Song at Midnight (夜半歌声 yèbàn gēshēng), depicted a deformed, grotesque figure with green lightbulbs for eyes. Only a day after the gruesome portrait was put up, a newspaper reported that a child who saw it was so freaked out that they died from fright. Never mind that the story was likely just a rumor; the movie’s marketing now cautioned adult viewers not to bring their kids to screenings, a warning that made everyone even more curious.

With Song at Midnight, director Mǎ-Xú Wéibāng 马徐维邦 would become the father of Chinese horror cinema. Based on Gaston Leroux’s Phantom of the Opera, and inspired by Lon Chaney’s classic Hollywood adaptation of the tale, Ma-Xu’s rendition was very much a unique take. Ma-Xu changed the setting to an abandoned theater in contemporary China, making his phantom on the movie’s infamous poster a former revolutionary and opera singer named Song Danping. Song at Midnight, with its unique blend of German Expressionist-style visuals and Chinese music, was a great hit at the box office. Its songs by legendary musicians Tián Hàn 田汉 and Xiǎn Xīnghǎi 冼星海 were popular for decades, while the film itself would inspire countless other Chinese horror movies.

The phantom, played by actor Jīn Shān 金山, is a lot more sympathetic than traditional portrayals of the disgraced opera singer. Song, disguised in a black robe, haunts the grounds of a theater that was burned down and abandoned. After an opera troupe comes to the theater to help fix it up, a young actor named Sun Xiao’ou is struggling to practice a song when Song appears and guides him through the piece. Sun is grateful, but afraid that his mysterious teacher might be a ghost. Taking off his hood, Song reveals his identity to Sun, bearing his charred, disfigured face. Over the course of a long flashback, Song reminiscences about the events that led him to become the theater’s gloomy phantom.

A decade earlier, Song was an accomplished actor and leftist revolutionary during China’s chaotic warlords period. The woman he loves, Li Xiaoxia, is a landlord’s daughter. The elder Li hates Song for his political activities, and orders the man to be tied up and whipped. Even after being tortured, Song refuses to give up his love for Xiaoxia. A jealous rival, Tang Jun, attacks Song and throws acid into his face. Although he survives, Song’s face has become permanently scarred. Too ashamed to show himself to Xiaoxia, Song fakes his death and takes refuge in the theater where he used to perform. Every night, he sings a song from the attic to comfort Xiaoxia, who lives nearby and has gone mad from grief.

Standing in the shadows, Song encourages Sun and pushes his fellow actors to perform Song’s trademark Hot Blood, a play that resurrects the troubled troupe’s career. When Tang Jun reappears, however, the characters’ fortunes take a radical reversal. Song at Midnight ends in tragedy, a mood carried by Jin Shan’s haunting performance of the doomed phantom. Ma-Xu’s direction is also commendable, with a talent for framing and building up suspense.

A perfect demonstration can be seen after Song’s acid attack. At the start of the scene, Song is surrounded by his family as his bandages are slowly removed, his body off-screen. When the bandages are off, Song’s mother and sister scream, while his father and a messenger stare at him dumbfounded. With his back to the camera, Song stumbles into view and wanders to a mirror, where the angle calmly shifts and reveals the man’s ghoulish face in the reflection. Ma-Xu’s handling of long stretches of silence, as when the opera troupe walks down a lonely corridor to a creepy room, also makes the atmosphere effectively eerie. Lastly, there’s the wonderful original soundtrack, a trio of songs that are both beautiful and sorrowful.

Song at Midnight would seal Ma-Xu’s reputation as a horror director. During the Second Sino-Japanese War, Ma-Xu made a spree of horror movies, including a direct sequel to his earlier masterpiece. Song at Midnight, Part II (夜半歌声续集 yèbàn gēshēng xùjí) (1941) needlessly brought back Song Danping with a Frankenstein-like story. While it provides a more bittersweet ending to Song’s downbeat life, like so many other horror sequels, Part II feels too tacked-on. A few years later, Ma-Xu collaborated with the Japanese on a propaganda flick about the Opium War, Eternity (萬世流芳 wànshì liúfāng) (1943). The movie practically ruined Ma-Xu’s reputation on the mainland, and he decided to exile himself to Hong Kong to work in the industry there. Appropriately, for a man devoted to the macabre, Ma-Xu died after being run down by a car in 1961.

He’s long been gone, but Ma-Xu Weibang and Song at Midnight have remained an important influence on Chinese horror. In 1962, the movie was resurrected with a two-part remake by Shaw Brothers Studio. Twenty years later, Song at Midnight was rebooted yet again under the same name, with a version in color by mainland director Yáng Yánjìn 杨延晋. An outing in 1995, The Phantom Lover (the same title of the original, 夜半歌声, in Chinese) featured Leslie Cheung (张国荣 Zhāng Guóróng) as Song Danping, emphasizing the story’s romantic themes and updating the setting to the 1940s. The fourth and most recent remake — and probably not the last — debuted as a mainland TV series in 2005, expanding the plot and butchering the horror elements over a 30-episode season. Still, even after all these remakes, you can’t beat the original with its stellar direction, shadowy cinematography, and its powerful phantom.

Film Friday is The China Project’s film recommendation column. Have a recommendation? Get in touch: editors@thechinaproject.com