China’s longest-surviving — and very illegal — LGBT magazine

Beijing-based GS began as a listings and lifestyle magazine geared toward the gay community before evolving into a respected outlet for commentary and longform journalism, dedicated to recording landmark events for the Chinese LGBT community. Twelve years later, amid a tightening media environment, it is the longest-running queer print publication in the country, and believed by many to be the last one standing.

In 2015, after a decade in circulation, the Chinese lesbian-oriented print magazine Les+ shut its doors for good when its co-founder and editor Sān Mù 三木 (pen name), or Sam, moved on to other projects. “I’ve had a predicament,” she wrote in a blog post announcing the closure. “Just how much impact can an underground publication have?”

Sam tried to sound upbeat about other means of advocacy, but the closure of Les+ came as a blow for another publication, whose staff worked just across the hall: a magazine called GS.

It was “like two people walking side by side, for one to suddenly vanish,” says Samuel Su (苏释 Sū Shì), GS’s editor-in-chief. A quasi-sister publication of Les+, GS had been around equally long. Now, four years later, it finds itself at a similar crossroads.

Many LGBT researchers in China believe that, today, GS — short for GaySpot (乐点 lè diǎn) — is not only the longest-surviving queer print magazine in the country, but also the last remaining, even as China increasingly clamps down on the visibility of an estimated 70 million queer people. But rather than lay low, as it has done for years, GS is trying to ramp up its reporting.

GS, with its three staff and team of freelancers, is a nonprofit started in 2007 as a source of event information for the gay community. Those were the days before gay dating apps like Grindr and its Chinese equivalent, Blued — and even before mainstream social media platforms like WeChat, which has become indispensable to gatherings.

By the time Su replaced GS’s founding editor in 2013, it had already grown into a male-oriented lifestyle magazine analogous to GQ. Sex, nightlife, celebrities, film, relationship advice, photos of buff guys: these were the needs at the time of Chinese gays seeking the material life, Su says, and indicative of the lax media environment that preceded China’s current regime.

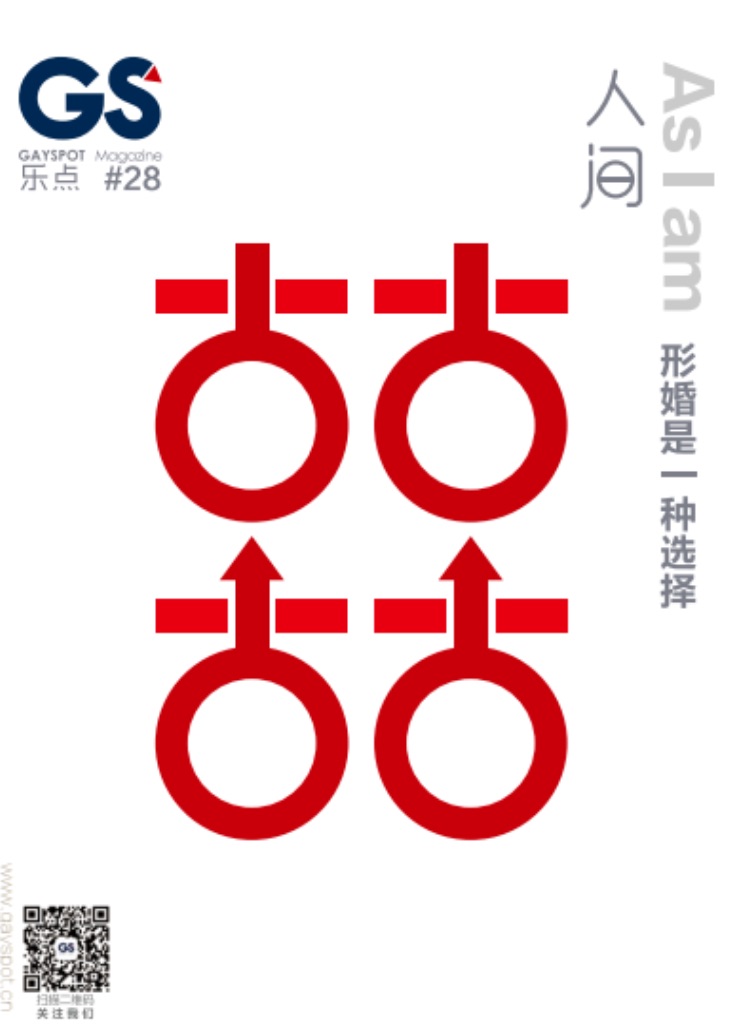

But under Su, GS morphed again, this time becoming a literary magazine that tried to tackle bigger issues using longform and narrative reporting. Occasionally it would dedicate an entire issue to one theme, such as its 28th installment on sham marriages, still common among Chinese LGBT people who are under immense pressure from their families to wed the opposite sex.

In 2015, China saw its first legal challenge to marriage laws when two men sued authorities in their town in central China’s Hunan Province for rejecting their marital application. The case drew widespread coverage, including from foreign media, but was eventually dismissed by the courts. In its five-page feature, GS got access not just to the men, but also their families, friends, and even previous partners, chronicling their upbringing, relationship, the trial, and their subsequent attempts to return to normal lives.

GS “3.0” had a penchant for documenting legal cases: China’s first discrimination suit brought by a transgender person in 2016 as well as a separate suit the same year involving coerced institutionalization; the first gay conversion therapy suit in 2017; discrimination trials won by a gay school teacher and an HIV-positive person in 2018; and high-profile suicides dotted throughout. These incidents, landmarks to the Chinese queer community, are sometimes glossed over or ignored entirely by mainstream papers. Su chose writers who could dive into the legal language to shed light on China’s system and its pitfalls, so that even if a case was lost, at least there would be a record.

According to Péng Yànhuī 彭燕辉 (who goes by Yànzi 燕子), head of the Rainbow Media Awards who researches Chinese law and journalism, GS’s pieces have been shared within the legal community as case studies.

Nowadays, the team only prints about two issues a year and posts a handful of articles a week on its public WeChat account (ID: gayspot) to a small but loyal fanbase, each fetching page views only in the low thousands. In comparison, Lifehack, another account that does gay male consumer-oriented workout tutorials, casual news, and product reviews, replete with photos of shirtless guys, celebrities, and memes, draws tens of thousands of clicks per article. GS’s funding, which used to come from foreign embassies in China, has been heavily restricted under China’s sweeping 2016 Foreign NGO Law.

Still, GS is a fixture, at least among activists. In late June, the annual Rainbow Media Awards took place in Shanghai, serving as both a finale for the city’s Pride events as well as a year-in-review of the best reporting on Chinese LGBT subject matter. In front of attendees and foreign dignitaries totaling several hundred — sizeable given the government’s hostility toward political gatherings and perceived “foreign influence” — one of GS’s co-founders was invited onstage as an award presenter, alongside representatives of the U.N.

GS’s small, relative successes have come amid an increasingly restrictive environment for LGBT content.

Just in the last year or so, Chinese social media companies scrubbed gay, then lesbian discussions from its platforms. Thanks to public outcry, these were later reversed, though only in part. Public opinion has not moved the authorities, however, who’ve been pushing chauvinism in the country by setting up new finishing schools and courses for young women, lashing out in state media at the supposed damage effeminate men do to the national image, and banning depictions of same-sex relationships, and even men’s earrings, on TV.

And in November, a prominent author of homoerotic fiction was sentenced to a staggering 10 years in jail for selling her book, in a case that shocked China’s fiction community. The incident was keenly felt by Su and his team because, like the novel and Les+, GS’s periodical is not approved for government-issued licenses that are required of every last print publication.

“Whereas before you could get away with being underground, now there were consequences,” Su says. For the most part, he shrugs off these events. In our conversations, Su’s answers — coming in quick, with little hesitation — were terse and dismissive.

But the chill on media has been real and widespread.

According to the Rainbow Media Awards organizers, increasingly pervasive censorship has caused a shift in LGBT coverage in mainstream outlets over the last 12 months. Their annual report, published in July, described double-digit declines in the number of articles on “rights and discrimination” and “workplace and society,” the previous year’s top two categories. “Cultural commentaries” and “celebrity news” — topics thought to be safe — have surged. An editor at one Shanghai-based outlet, where LGBT was a major topic, said his publication cut its output by two-thirds between 2016 and 2018. He suspected that management had put a quota in place.

To survive, GS has kept its head down. For one, the team is content with its mediocre traffic. The writing style is also deliberate: Hard news is too bellicose; a soft, narrative tone is less likely to trip the censors, according to Su. The staff gives the magazine away for free to eliminate any profit, and is tight-lipped when it comes to circulation numbers (for fear of appearing influential and drawing attention from the authorities), beyond a vague claim of being in more than 60 cities across China.

“It’s incredible that the magazine lives on,” says Peng, head of the Rainbow Media Awards, with all things considered. Given widespread efforts to “survive first, grow audience second,” it’s not surprising that even among long-time Chinese LGBT researchers and activists, several of whom I reached out to, few are aware that at least one other queer magazine had recently surfaced. “Missionary,” with two issues out, seems to have adopted a strategy similar to GS’s.

When I asked Su if the low clicks meant that ordinary queer people didn’t actually care much for GS’s content, he answered that it didn’t matter.

“Chinese gays are such letdowns,” he said. “In the big cities, their lives are all converging. They all work out. They all have the same haircut. They have facial hair and wear shorts like these.”

He gestured at the chinos and polo I had worn to the interview. “All they care about is their little joys,” he said.

GS, you see, needs to have vision. In fact, Su has a two-year plan. While the team works on its upcoming issue on queer life in small-town China, it has partnered with the Rainbow Media Awards to reach out to mainstream outlets to try to help them navigate censorship and shore up their LGBT coverage, going as far as to offer them copy. In doing so, it is trading in the safety of its long-nurtured cult status and risking exposure.

“We need to actively try and expand, otherwise, this space will only shrink,” says Peng, who added that there is still room for LGBT stories to be told.

“It’s possible that this will bring risks. I don’t know. But we have a responsibility,” says Su. “All I know is that it’s the right thing to do.”