Rising sea levels to turn Shanghai into a swamp — study

The new study finds that the number of people vulnerable to sea level rise is tens of millions higher than previously thought, and that China is one of the countries worst affected.

A new study on sea level rise due to climate change was published on Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications, titled, “New elevation data triple estimates of global vulnerability to sea-level rise and coastal flooding.” It has major implications for Chinese coastal cities like Shanghai and Guangzhou.

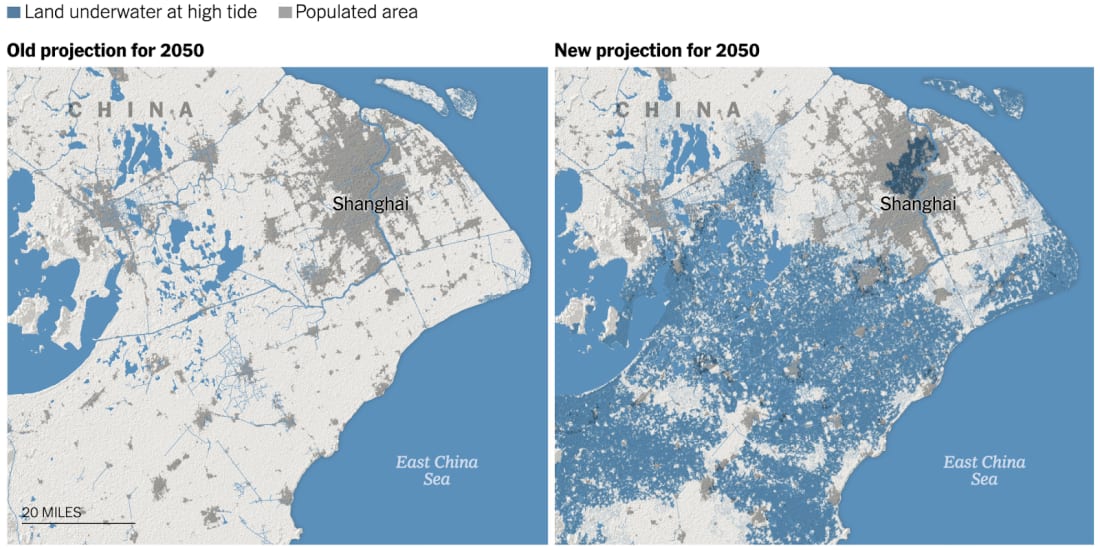

The study measured land elevation from satellite data using a method that the authors claim is far more accurate than previous methods, which “struggle to differentiate the true ground level from the tops of trees or buildings,” Scott Kulp, a researcher at Climate Central and one of the paper’s authors, told the New York Times.

Comparing the true elevation data to the populations of coastal cities and consensus estimates of sea level rise (from 0.5 to as much as 2 meters by the end of the century), the authors found that the number of people vulnerable to sea level rise is tens of millions higher than previously thought. China is one of the countries worst affected:

- Approximately 43 million to 57 million people in China currently live on land that will be underwater by the end of the 21st century, according to models in the paper.

- China alone accounts for 15 to 28 percent of the world’s total populated land that will likely be under sea level.

- This is largely because the Yangtze River Delta, where Shanghai is located, and the Pearl River Delta, where Guangzhou and other cities are located, have high concentrations of people in low-lying land.

- Besides mass relocations of people, there are defensive measures like levies that will have to be built to deal with this problem in the long term. Per the NYT:

The findings don’t have to spell the end of those areas. The new data shows that 110 million people already live in places that are below the high tide line, which [Benjamin Strauss, a paper coauthor] attributes to protective measures like seawalls and other barriers. Cities must invest vastly greater sums in such defenses, Mr. Strauss said, and they must do it quickly.

But even if that investment happens, defensive measures can go only so far. Mr. Strauss offered the example of New Orleans, a city below sea level that was devastated in 2005 when its extensive levees and other protections failed during Hurricane Katrina. “How deep a bowl do we want to live in?” he asked.