Ilham Tohti’s Sakharov Prize and the desecration of Uyghur society

Ilham Tohti was famous for pushing back against the material and social dispossession of Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims. When even this moderate scholar was silenced five years ago, it signalled that there was no more space to publicly suggest ways to oppose the elimination of Uyghur culture. The Sakharov Prize honors the dignity of Uyghur social life and the way Ilham Tohti strove to protect it.

Ilham Tohti was famous for pushing back against the material and social dispossession of Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims. When even this moderate scholar was silenced five years ago, it signalled that there was no more space to publicly suggest ways to oppose the elimination of Uyghur culture.

The Sakharov Prize honors the dignity of Uyghur social life and the way Ilham Tohti strove to protect it.

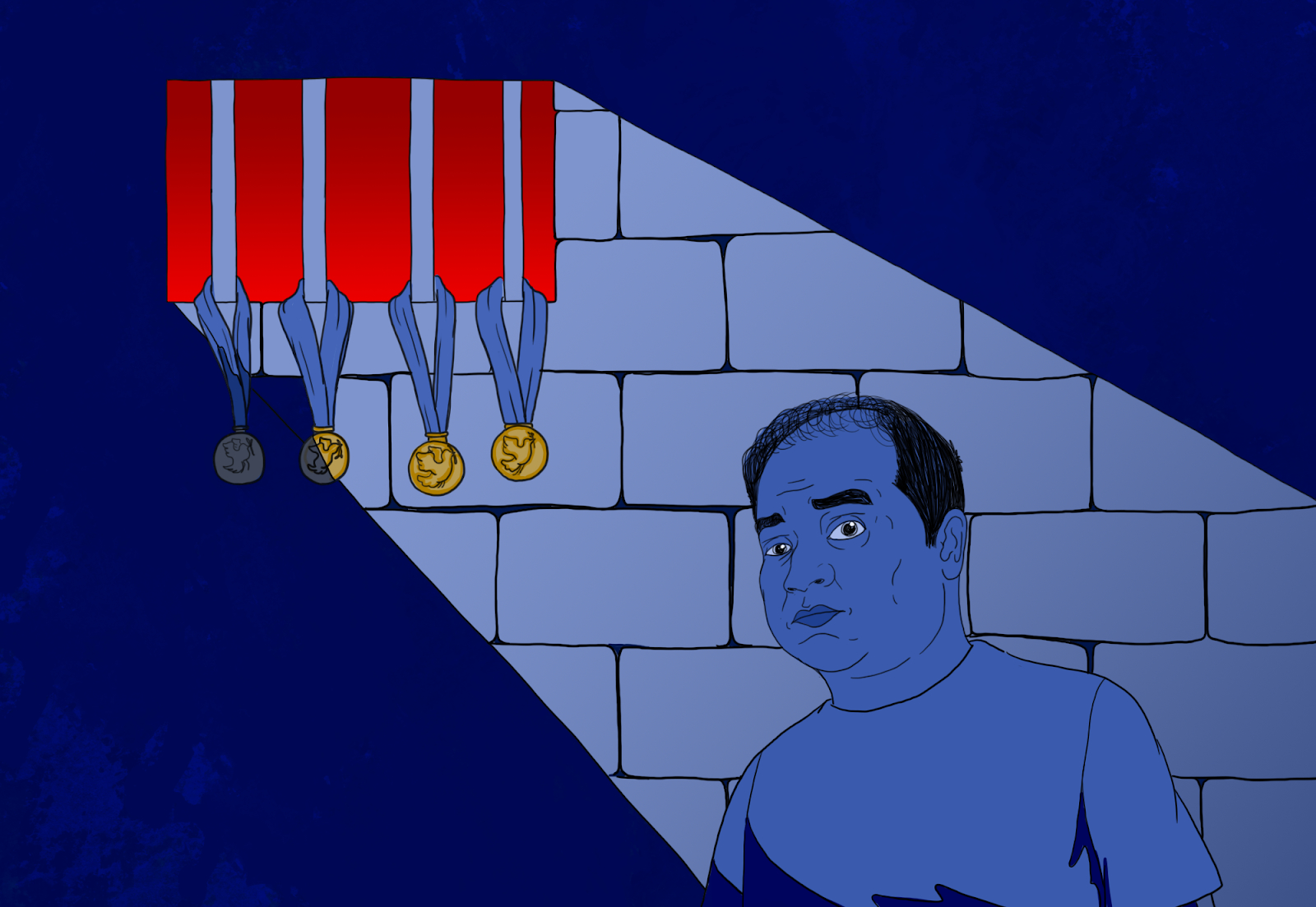

Illustration by Derek Zheng

On October 24, 2019, it was announced that the Uyghur public intellectual Ilham Tohti would be awarded the European Parliament’s highest human rights award: the Sakharov Prize. Ilham, a marxist economist from Beijing’s Minzu University, was famous for pushing back against the material and social dispossession of the Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims.

Up until July 6, 2009, a day after large scale protests and violence began in Ürümchi, Ilham had edited a Chinese language website based in China called “UighurBiz.cn,” which in Uyghur means “We are Uyghurs.” Like his friend Ai Weiwei, who also grew up in Xinjiang, Ilham used his position of influence to build a digital platform that advocated for the civil rights of those who were most vulnerable in contemporary China. Whether it was the victims of the Wenchuan earthquake or Uyghurs who were losing their land, loved ones, or right to study their own language, both of them asked Chinese authorities to defend the rule of law as enshrined in the Chinese constitution.

After July 5, 2009, both of their websites were blocked. Up to that point, Ilham’s site, as the only source of independent news and commentary on Xinjiang in China, had reportedly received 1.2–1.5 million page views in China per day, making his audience share significantly larger than Ai Weiwei’s reach of 70,000 followers.

In the years that followed, Ilham, with the help of Uyghur students and colleagues, built a new website called UyghurBiz.net that was based in the United States. For the next four years, the site reportedly continued to have up to 300,000 page views from visitors in China each day. The size of Ilham’s audience is important, because it meant that he had significant influence in the urban Uyghur community back in Xinjiang, among those who had access to the internet and in the broader Han community. It is likely that he was seen as a threat to Chinese state authority simply because of the scale of his digital media platform.

Ilham Tohti takes a selfie with Tsering Woeser and Ai Weiwei in May 2013.

I first came across Ilham Tohti’s work in 2013. As a language student, I poured over his website translating his essays and reports into English as a way of sharpening my Chinese research skills. Over and over I was taken with how fair and precise he was in assessing the material conditions and structural violence that confronted Uyghurs.

For instance, in his most famous systematic account of the situation, a 2013 policy brief written at the request of Chinese authorities, he noted that “according to official government data, only 17 percent of ethnic Uyghur university students in Xinjiang manage to secure a full-time job by the time they graduate.” Continuing, he noted that the vast majority of Uyghurs were excluded from even this precarious path to employment. Only around 10 percent of the entire population of Uyghurs made it to regional centers either as migrant workers or students. He wrote, “most of Xinjiang’s Uighur population is concentrated in the rural south, where the average amount of arable land per capita is less than one mu [亩 mǔ], or one-sixth of an acre.” Based on his analysis of the material conditions and modes of economic production in Uyghur society, the causes of conflict in Xinjiang stemmed from widespread unemployment, the erasure of Uyghur language education, religious restrictions, ethnic alienation, distrust of minority officials, the presence of the paramilitary “bingtuan” organization, and the ineffectiveness of regional Han officials.

In my reading of his website, one article in particular stood out to me. It was a story from early 2013 that described the way the local authorities in the city of Shihezi, the capital of the People’s Production and Construction Corps, were planning to demolish a Muslim cemetery to make way for real estate development. Although UyghurBiz.net was deleted and much of its archive was lost when Ilham was arrested in January 2014, a new website called Uyghur Archive recently recovered more than 2,700 articles from the site, including this piece on the Shihezi cemetery. Rereading it led me to a later article posted by Radio Free Asia on November 1, 2013, where they describe the way the destruction of the Uyghur cemetery was at least temporarily halted by the protests of reportedly more than 1,000 Uyghurs and other Muslims. The story described a tense standoff between police and Uyghur women who camped in the cemetery for several days to prevent the bulldozers from moving in. It is unclear how the standoff ended.

Uyghur and other Muslim women and men stand in protest of the destruction and desecration of a Muslim cemetery in Shihezi, Xinjiang in October 2013. (Image by anonymous via RFA)

On November 2, 2013, one day after the story of the cemetery demolition protest was published, state agents rammed Ilham’s car near the Beijing airport, terrifying his two small children who were in the back seat. Although the cemetery protest and the violent confrontation with the police in Beijing were likely not directly linked, what the agents told Ilham was quite similar to what the police were telling protestors in Shihezi. As the Han dissident Hu Jia noted in a conversation with journalist Ian Johnson, the state operatives told Ilham repeatedly that they wanted to nongsi (弄死 nòngsǐ) his family. This term, Hu explained, implied that they wanted to put his entire family to death.

The state agents in Beijing, like the police in Shihezi, were threatening to remove all traces of Uyghur social life from the space that Chinese authorities had claimed their own.

I heard the news that Ilham had been sentenced to life in prison while I was living in Ürümchi in September 2014. It sent a chill through the Uyghur student body at the college where I was based. They whispered to each other about the significance of the sentence. It was much longer than anyone had expected. Nearly all of the Uyghurs I spoke with, both students and public intellectuals, had agreed with Ilham’s moderate stance toward resolving the antagonism between Uyghurs and the Chinese state. Now, like Ilham, they realized that all of them could be accused of “separatism.” There was no space to publicly suggest ways to oppose the elimination of Uyghur culture. They told stories of people being arrested for accessing the UyghurBiz site or downloading videos that discussed the injustice of his trial.

Nearly all of the Uyghurs I spoke with, both students and public intellectuals, had agreed with Ilham’s moderate stance toward resolving the antagonism between Uyghurs and the Chinese state. Now, like Ilham, they realized that all of them could be accused of “separatism.”

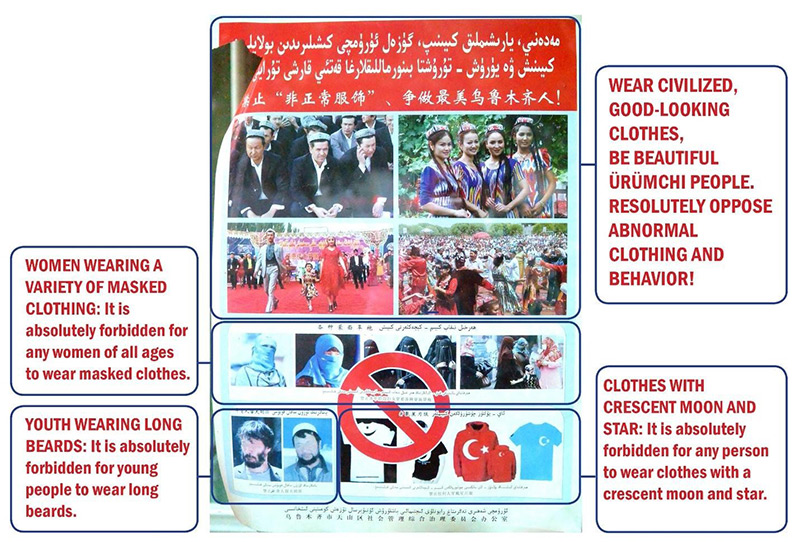

During the same week that his sentence was announced, authorities in Ürümchi pasted large posters throughout Uyghur neighborhoods offering rewards to anyone who turned in a potential “extremist.” The posters, which were posted by neighborhood watch units that monitored every housing complex, stated clearly that they would detain any young person who had a religious appearance or any Islamic symbolism on their clothing. Religious discrimination was now institutionalized in public, and the mass detention and “reeducation” of the Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims began to swing into motion.

Posters that were erected throughout the Uyghur majority areas of Ürümchi in September 2014, the same month that Ilham Tohti was sentenced. (Image by Timothy Grose)

In the months leading up to the announcement of the 2019 Sakharov Prize, there have been numerous reports of the systematic desecration and destruction of Uyghur cemeteries and associated holy shrines. Unlike in 2013, now there are no protests against these erasures of Uyghur Indigenous life. Instead there is resigned acceptance.

The reverence Uyghurs have for their ancestors and the Indigenous traditions and places they came from is at the heart of what Ilham stood for and why the Sakharov committee recognized his work.

In a new report published by the Uyghur scholar Bahram Sintash, multiple Uyghurs recount the anger and despair they felt as they saw notices announcing the demolition of the cemeteries where their parents were buried and, soon after, the way cemeteries were turned into parking lots, real estate developments, “happiness” parks and blank spaces. A young Uyghur woman named Marpigha Yusup told Sintash:

The Uyghur community in Hotan cares about each other and would have willingly volunteered to help move graves of strangers, especially in this kind of situation, but so many people are being held in camps and people outside worry about being targeted for seeming religious in the government’s eyes. We worry that my grandfather’s grave would end up as an unclaimed grave and that the government will treat his remains as trash. The government does not even care about us and our culture while we are alive, so I don’t believe they would care about the dead Uyghurs inside the graves.

A close Uyghur friend of mine who lives now in North America told me that he recently asked his mother if she visits the grave of his grandmother. When he was a child, his father had taught him to visit it every Monday and Thursday to say a prayer for his grandmother’s wellbeing in the afterlife. His mother shook her head. She said, “We just visit it from the road when we are driving by. The authorities put a fence around it so we can’t go inside. They told us that soon they will move it.”

The threat of “putting his family to death,” which state agents used to terrify Ilham’s family in November 2013, has slowly been implemented on the level of Uyghur social life itself. This looks like the slow death of mass detention and the removal of cultural leaders like Ilham, but it is also present in the erasure of the traces of ancestors.

As the work of Rian Thum and others have shown, the spiritual life of Indigenous Uyghur society and history is tied directly to these sacred landscapes. It is this life, and Uyghur civil rights, that Ilham Tohti worked so hard to protect. In an October 2019 presentation on life after the desecration of Uyghur sacred landscapes, the scholar Elise Anderson described a visit to the shrine to Mahmoud Kashgari. Her Uyghur acquaintance had brought a bottle with her to fill with the water that flowed from a spring at the shrine. As they knelt by the stream she asked Dr. Anderson, “Can’t you see why people would see a place like this as holy?” For Turkic Muslims, cemeteries and shrines are peaceful, blessed places. They are places that always welcome travelers and give comfort to those who were suffering. Destroying such sites is not only a way of desecrating Indigenous ancestors, but also a way of eliminating Indigenous futures.

Anyone who has spent time with Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and others in northwest China and really seen how they interact with their land can understand the reverence they have for their ancestors and the Indigenous traditions and places they came from. This respect is at the heart of what Ilham stood for and why the Sakharov committee recognized his work. Regarding these forms of social elimination and opposition to them, Dr. Anderson quoted a Uyghur proverb, “You can’t cover the sun with a coat flap” (Uy: künni ıtek bilen yapqili bolmas). The “putting to death” of Ilham and the way of life he stood for cannot be covered over; the dignity of Uyghur society will always shine through. The 2019 Sakharov Prize has helped to ensure just that.

Darren Byler’s Xinjiang Column is published on the first Wednesday of every month. Previously:

Xinjiang education reform and the eradication of Uyghur-language books