‘The ambiguity between truth and fiction’

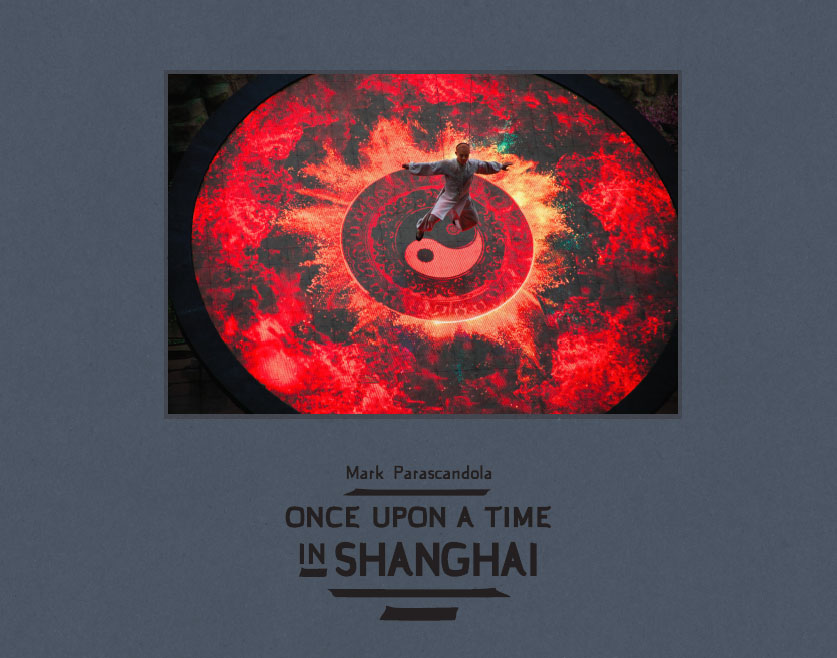

Starting tomorrow until Friday, December 6, our photo section will feature images from photographer Mark Parascandola’s most recent book, Once Upon a Time in Shanghai, on sale as of today via Daylight Books.

Chinese cinema appears to be on the cusp of a golden age. According to some estimates, it will be the world’s largest cinema market by next year. In order to keep up with heightened demand, vast content production facilities are springing up, some comprising entire towns, including one that boasts a reconstruction of the Forbidden City.

Mark Parascandola, a Washington, D.C.-based photographer whose work examines the role of film and images in shaping collective perceptions of reality, has sought to capture the spirit of these immense content production facilities. His recent book, Once Upon a Time in Shanghai, sheds light on China’s rapidly expanding film industry and explores the tensions between truth and fiction, past and present.

We recently spoke to him about his work.

The China Project: What led you to embark on this project?

MP: I actually have a background in public health research, which is not necessarily directly related to this project, but it has informed my photography work. That’s part of what’s driven my interest in the history of places, and trying to understand the culture around them. I did a previous book called Once Upon a Time in Almería, which was about the legacy of Hollywood in Spain in the 1960s and ’70s, where under the Franco regime Hollywood directors actually went to Spain, making a lot of films there. At the time, the Franco regime was seeking foreign investment, promoting tourism, and also promoting filmmaking there because they wanted to give the world a different version of what they read in the news about Spain at the time. There were also a lot of Spaghetti Westerns made in Almería — by Sergio Leone as well as a lot of films with Clint Eastwood were made there. So I photographed all of the locations and some of those old Western movie towns that are still there. So that was what got me interested initially in the whole theme of movies and movie sets.

Why did you choose China for this project? What was the initial spark that led you from Almería to here?

MP: I hadn’t had much experience with China before, apart from visiting a couple of times for personal travel, until about five years ago when I had a fellowship in Beijing. I was living in Beijing for about three months, and so I got a chance to get to know China a little better. And at the time I read an article about how you could go visit one of the movie production sites — this was the China Film and Television Base (中国电影旅游拍摄基地 zhōngguó diànyǐng lǚyóu pāishè jīdì) in Huairou, outside Beijing. So I thought, this sounds cool, as I had already been photographing these films sites in Spain, so I thought I should go check it out.

One important aspect when considering the case of China, and especially its domestic movie industry that is taking off, is the role of the state, which is far greater here than it is elsewhere — certainly in Hollywood. When you were photographing these sites, did you see the presence of the state manifesting itself?

MP: I think it’s clearly an important part of understanding, especially the large sets that are constructed, such as the Hengdian World Studios (横店影视城 héngdiàn yǐngshì chéng), where they reconstructed the entire Forbidden City. Because there is a lot of state control and censorship of the mainland Chinese film industry, there are a limited number of themes that filmmakers can deal with, so they tend to fall back on the familiar historical themes. A few of the same themes we see over and over again: we see dramas set in the Forbidden City, we see Shanghai under the Japanese occupation, we see the Communist Revolution, and certain important themes in Chinese history that recur over and over again in films and television. So that means that it’s actually worthwhile to build these huge sets because they are used over and over again, whereas that might not be the case in Hollywood. What I noticed in visiting these sites is that it’s not so much the direct influence of the state, but the fact that the history of China is always present because all of these set pieces are all built around certain historical episodes.

The China Project: Some of these sites have even become tourist attractions of their own. But of course, they’re not real historical sites — to some extent they’re illusions. How does this phenomenon relate to your previous interest in exploring the ambiguity between truth and fiction?

MP: Some of the sites are open for tourists. Hengdian in particular received around 12 million visitors last year, so they really depend heavily on tourism as an important source of revenue. It’s almost entirely tourists from mainland China; I see very few foreigners visiting these sites. And [mainland Chinese tourists] are of course familiar with the settings and they know the films that were made there, so it has more significance to them. But I found it fascinating that people travel so far to visit a fake Forbidden City, when they could go to the real one instead.

The size of these sets and film production villages that have cropped up over recent decades is unprecedented — could you speak a bit more about the scale of the sites, and how they differed from other facilities you’ve photographed?

MP: I don’t think there is anything on this scale anywhere else in the world. Even in Hollywood these days, they don’t construct sets like this, as a lot more work is done in the studio or on location. So to me it harks back to the times of Cecil B. DeMille and other early filmmakers who used large-scale productions with casts of thousands. This is the scale that you see in these massive Chinese film sets. There are other sites — the Shanghai Film Park (上海影视乐园 shànghǎi yǐngshì lèyuán) has several city blocks reconstructing Nanjing Road circa 1930s — and they’re not just facades, they’re actually complete buildings and city neighborhoods that have been constructed.

About a dozen of these “movie towns” are represented in the book, but there are many more around the country. Many that I visited were around Shanghai, but I also visited Changchun (长春电影集团公司 zhǎngchūn diànyǐng jítuán gōngsī) in the north, which was one of the early studios that was important for the 20th-century Chinese film industry. And also the Zhenbeibao Western Film Studio (镇北堡西部影城 zhèn běi bǎo xībù yǐng chéng) in Yinchuan, which is where they have produced a lot of epic historical films.

These films are largely consumed by the Chinese public, and are not being watched abroad very much, whereas Hollywood films have tended to have a more universal viewership. Even the sites you mentioned in Spain were based largely on the Hollywood Western image. Do you think there is potential for Chinese films — produced on this scale and with vast amounts of resources — to expand their reach globally over the coming decades, or will the industry remain relatively insulated?

MP: I think it’s inevitable that the Chinese film industry will become more global, and we’re already starting to see that. This year the Wandering Earth (流浪地球 liúlàng dìqiú), a blockbuster science fiction film — kind of different for China — actually got shown in American theaters and is now on Netflix as well. So, some of the newer films are starting to get more of an audience in the U.S. I think also that because the Chinese film-viewing market is now the second largest in the world, and is probably going to overtake the U.S. soon, Hollywood is also increasingly looking to China. So I think we’ll likely see more U.S.-China co-productions.

Did you witness any foreign collaboration when you were photographing the sites?

MP: Yes. At the Xiangshan Film and Television City (象山影视城 xiàngshān yǐngshì chéng), one of the major film cities south of Ningbo, there was a production going on for a movie about an American pilot during World War II who lands in China and is helped by the locals. So this is a Chinese film, but it has a very international theme that might appeal to a U.S. audience. They had reconstructed the former American Chengkung Airfield (Yunnan Province) on an empty field there, which certainly seemed a little odd and out of place.

A common trend in your work is to examine various tensions between history and the present. How did you attempt to explore this theme while photographing these subjects in China?

MP: I found it fascinating to see the contrast between history and the present. So many of the movies and TV series that are made in China have a historical theme. But yet, China obviously is rapidly changing, so there is definitely a contrast that is striking. Also I think it’s intriguing in the sense that the historical films are historical but they’re also make-believe; so they’re not necessarily seeking the truth, they’re telling a particular version of Chinese history.

Once Upon a Time in Shanghai includes 70 color photographs and an essay by UCLA China scholar Michael Berry. You can purchase it on Amazon.