Chinese celebrity chef roasts Michelin’s Beijing guide

Michelin, the French dining guide, has come under attack in China after launching its first Beijing edition on November 28, featuring 23 starred restaurants (Xin Rong Ji was the only three-starred restaurant) and 77 other recommendations. Some Beijingers and food critics were disappointed by Michelin’s selection of food items, which they say are not exactly representative of China.

Unlike the Michelin editions in Shanghai and Guangzhou, the Beijing edition included more local specialty foods, including mung bean milk (豆汁 dòuzhī, a fermented byproduct of cellophane noodles that smells like raw egg), bitter flapjack (卤煮火烧 lǔzhǔ huǒshāo, a stew of pork lungs, intestines, and livers served with flatbread), 炒肝 chǎo gān (starchy pork livers and intestines), 爆肚 bàodǔ (halal tripe traditionally prepared by the Muslim Hui people), Peking crispy-skinned duck, and noodles with soybean paste (炸酱面 zhájiàngmiàn).

Dǒng Zhènxiáng 董振祥, a Beijing celebrity chef and the founder of the school of Imaginative Cuisine, claimed in an widely-circulated essay, titled “Pursuing Aroma and Expelling Stench in Food: A Reflection of Michelin’s Rating of Chinese Restaurants,” that Michelin’s selection of Beijing local dishes was fraught with ancient stereotypes. Dong cited the 1972 documentary Chung Kuo, Cina by Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni, which “reflected the real situation of China at the time, but was filled with novelty-seeking scenes of the darkest sides of Chinese society — like foot-binding and jumpsuits.”

“Michelin’s ratings are on par with this kind of novelty-seeking attitude,” wrote Dong, who founded the Peking duck restaurant Da Dong (two separate branches in Beijing each received one Michelin star; he also owns the one in New York, stylized “DaDong”).

“The sense of cultural superiority communicated in their selection of Beijing dishes creates an illusion that the culinary level of ordinary people in China remains on tripes, offal, and viscera. But these foods obviously do not capture mainstream Chinese culinary culture, let alone the artistic elegance of Chinese cuisine.

“We hope Michelin can obtain a deeper understanding of the place where the food is inspected. Get rid of the arrogance, ignorance, and prejudice, and be left with our shared passion for the soul of gastronomy.”

Michelin has been rating restaurants in Hong Kong and Macau since 2009. Shanghai became the first Michelin city in mainland China in 2016, where 26 restaurants were awarded, with Ultraviolet getting a coveted three stars. Guangzhou was added two years later.

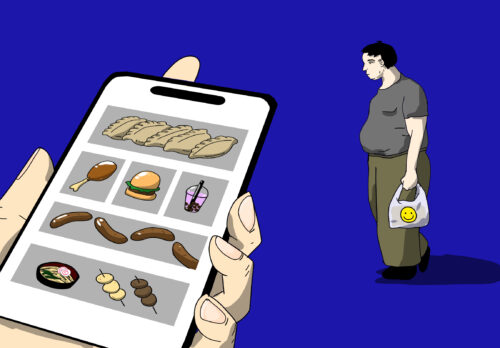

Michelin has not gained much traction in mainland China. Although its selections may attract some deep-pocketed diners, it has not become a particularly sought-after guide. Its spinoff guides for the more value-conscious — Bib Gourmand and Good Plates — also has a hard time competing with Dianping, the Chinese equivalent of Yelp. And Michelin remains foreign, for better or for worse. Some locals in Guangzhou denounced Michelin’s debut in the city in 2018, claiming that the starred restaurants, with their exorbitant Cantonese dishes chosen by inspectors with Eurocentric tastebuds, were out of sync with the ethos of Cantonese food.

Dong ended his article by stating his hope that there would be new lists capable of expressing Chinese “cultural confidence.”

The largest food delivery and service group, Meituan Dianping, created a “Black Pearl” rating system in 2018, aiming to rate Chinese haute cuisine with “a deep love and understanding of Chinese culture and food.” Black Pearl 2019, announced in January, awarded 287 restaurants, including 20 three-stars and 77 two-stars, in 22 Chinese and five foreign cities. Some 70 percent of these restaurants serve Chinese food. The average spending per guest is at RMB 836 ($120).

Black Pearl‘s rating mechanism is similar to that of Michelin’s, with a council of food critics and inspectors who go to restaurants and inspect based on vague culinary aesthetics. While Michelin assesses the quality of the products, mastery of flavors, cooking techniques, the personality of the chef, harmony of flavors, and consistency, Black Pearl judges standards of cooking, diner experience, and innovation in cultural heritage.

On paper, Black Pearl has a grandiose mission to promote Chinese cultural confidence, which, of course, would please many. According to Meituan, a company that occupies 65.8 percent market share in takeout delivery services, it knows more about Chinese food than foreigners, namely the people behind Michelin.

Dianping CEO Wáng Xìng 王兴 said at a 2018 press conference that “Meituan does not want to earn money from the list,” and that a desire for profit will make the game unfair. Perhaps Black Pearl itself does not generate revenue, but it creates more venues and opportunities for the expansion of the Meituan digital service empire. Meituan stated in 2019 that restaurants listed by Black Pearl saw an average of a 97 percent increase in online traffic and 30 to 70 percent in guest flow. Restaurants would be incentivized to use Meituan’s cashing services, catering software, and its B2B food supply-sourcing platform Kuailu Jinghuo. As Meituan expands to the realm of high-end dining, Black Pearl is Meituan’s stepping stone for connecting with restaurants.