Apologizing for the Cultural Revolution (who should do it?)

This month’s Kuoras have examined the Cultural Revolution. Last week’s column was about foreigners who lived in China during the era. To wrap up the series, this week’s column comes from one of Kaiser’s answers originally posted to Quora on August 29, 2014:

Should the Chinese Communist Party apologize to Chinese citizens for what they did during the Cultural Revolution?

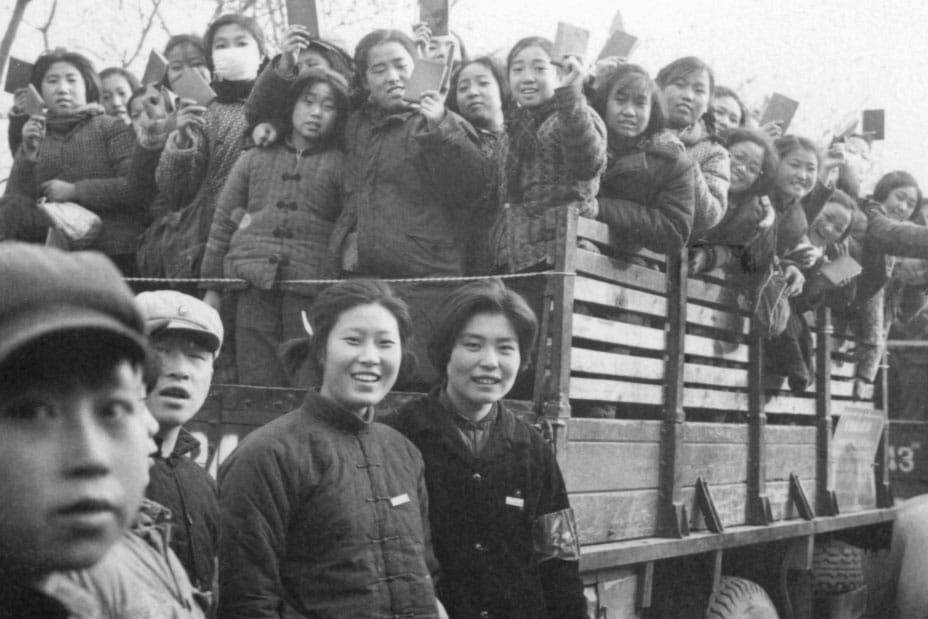

There have been a number of apologies, but these are issuing not from the Chinese Communist Party itself but rather from individuals who took part — usually as Red Guards — in the persecution of innocents who were denounced, beaten, tortured, and imprisoned during the Cultural Revolution. What is significant is that the Party/state has allowed these acts of public contrition to run in state-controlled media.

Should the Party apologize? There’s no question that the leadership since Mao’s death, under Huá Guófēng 华国锋, Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平, Jiāng Zémín 江泽民, Hú Jǐntāo 胡锦涛, and Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 in that order, hasn’t had a real reckoning with that dark chapter, hasn’t encouraged a public reckoning, and has at best just recently begun to allow the apologies to begin. But I suspect that most people who think it should actually apologize don’t quite understand what happened during the Cultural Revolution.

Two important things to know: First, the Party was itself the primary target of the Cultural Revolution. That strikes many people as odd: Wasn’t Mao, the leader of that very party, the man responsible for the Cultural Revolution? Yes he was. But he had been “kicked upstairs” during an interregnum that spanned the years 1961 to 1965, when the actual Party leadership was in the hands of Liú Shǎoqí 刘少奇 and Deng Xiaoping, and the folly of the Great Leap Forward and resulting horrific famine had caused many within the Party to champion the more technocratically-driven, centrally-planned economic policies that Liu and Deng represented. In the spring of 1966, Mao basically mobilized “the people,” calling on them to attack the “capitalist roaders” and tear down all these structures of what he called bureaucratism and elitism. The Communist Party was chief among these.

Red Guards attacked not only the Party, of course; they also went after intellectuals, professors, and schoolteachers, hospital administrators and doctors, factory managers, and just about anyone else in a position of putative or actual authority.

The second thing to know is that the Communist Party as it is today, while it still refuses to disavow or renounce Mao and his legacy, came to power in 1978 in direct opposition to the policies of the Cultural Revolution. Deng’s rise to the top was all about reversing the Cultural Revolution and undoing its damage, by rehabilitating people who had been persecuted, bringing back urbanites who had been sent down to the countryside, dismantling radical collectivization in agriculture, and so on.

Kuora: Mao Zedong’s legacy — and Deng Xiaoping’s role in preserving it

Perhaps the Party today, because it does still bear the same name and still ostensibly subscribes to the same core ideology that the Party did under Mao, bears some blame for the Cultural Revolution. But when you consider that the current president was himself the son of an official (Xí Zhòngxūn 习仲勋) who was purged by Mao, sent down to work in a factory in Henan in 1966, then actually jailed in 1968, I have to wonder whether “apology” is appropriate. A reckoning, yes. Allowing any and all apologies by perpetrators of crimes during that time, yes. And I’d love to see a more honest appraisal of Mao’s record. But probably not a Party apology per se.

Kuora is a weekly column.