The making of an icon: Sanmao’s ‘Stories of the Sahara’

Confessional prose, a wanderlust travel persona, and personal tragedy have helped sustain Sanmao’s enduring legacy.

Since Sanmao’s self-reflective essay collection Stories of the Sahara was first published in Taiwan in the mid-1970s, her writing has captivated readers on both sides of the Taiwan Strait, and inspired generations of young Chinese women to adopt the author’s English name, Echo. This collection is now available to English-language readers for the first time via a translation by Mike Fu, published through Bloomsbury Press on January 14.

Born Chén Màopíng 陈懋平 in 1943 in the mainland Chinese city of Chongqing, Sānmáo 三毛 grew up in Taiwan. Her passion for literature was apparent from a young age. She read the Chinese classics and studied English literature while in middle school, even taking a year away from formal education to concentrate on the latter with tutors. As a young woman, she learned German and Spanish and studied in Spain, where she met her future husband, José, and worked in the law library at the University of Illinois.

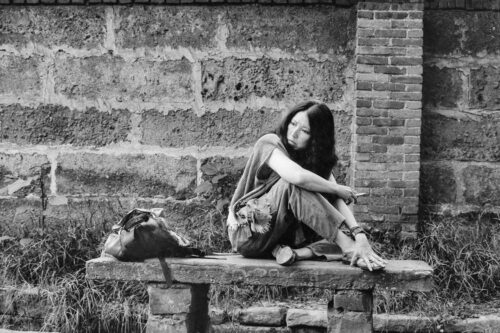

From the book’s earliest essays, it becomes clear how Sanmao’s whimsical solo traveler persona came to symbolize an alternative way of life among her earliest generation of readers, whose own lives were shaped by the oppressive political environments of mainland China and Taiwan during the 1970s.

Sanmao explains in her writings what drew her to the desert in the first place: the desire to be the “first female explorer to cross the Sahara,” even noting that the thought of it often kept her awake at night. Sanmao is a capable and worldly traveler, detailing her endeavors deep in the desert. She even confronts a strange man in the middle of a cemetery while on her way home one night.

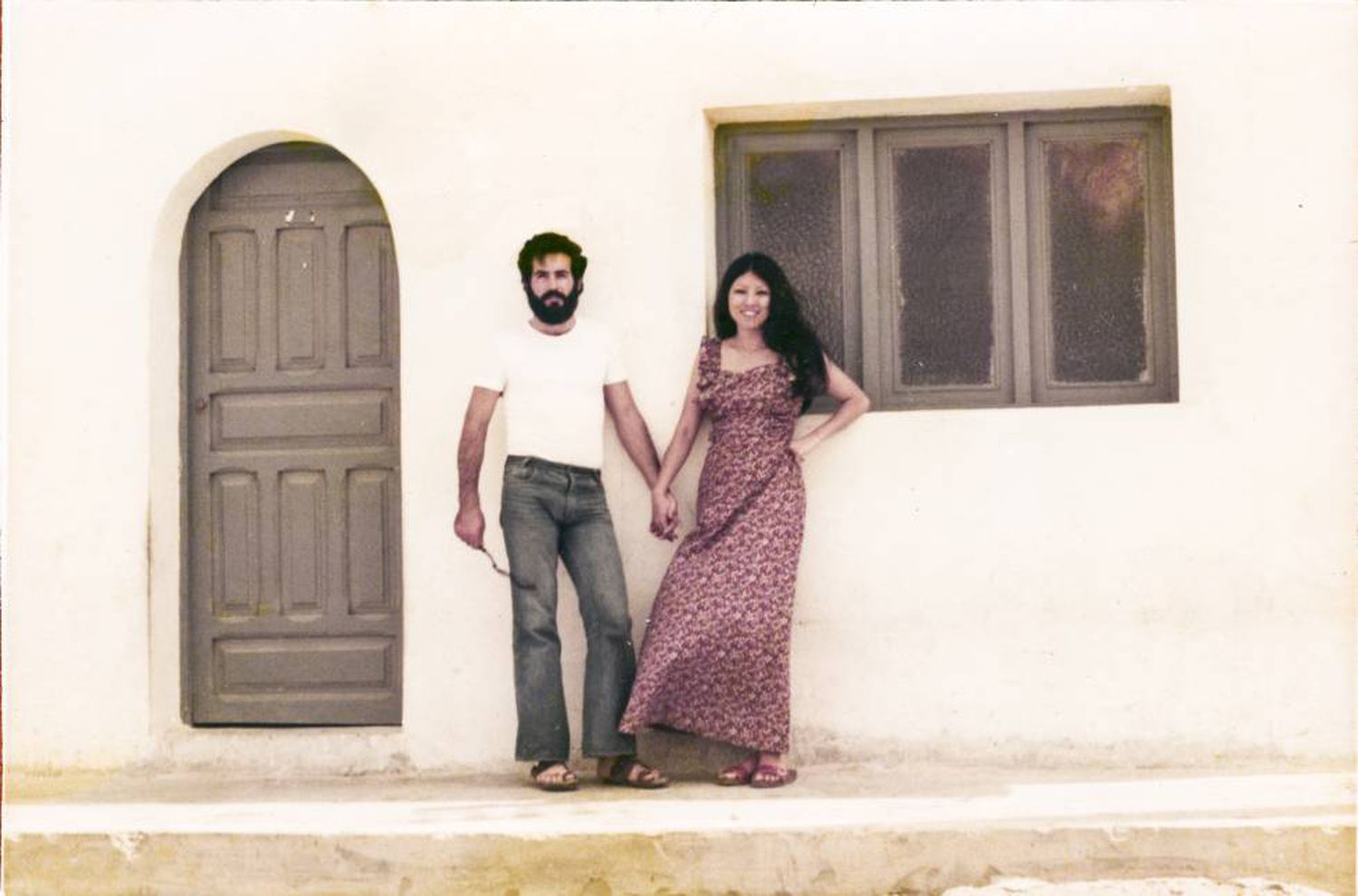

Sanmao’s longing for exploration and, in turn, independence from the social expectations of the time becomes even more explicit in another essay detailing her wedding to José, which takes place only after the pair relocate to the Sahara. Sanmao asserts that while she was prepared to marry José, she was not “willing to toss aside” her “independence” and “carefree spirit.” If marriage were to come at the expense of these things, she warns they’d better “scrap the whole idea.” José chooses to respect Sanmao’s independence, and Sanmao in her writing quickly establishes José, who appears as a key character throughout the majority of the chapters, as her endearing — though more apprehensive — partner in crime.

Elsewhere, Sanmao infuses a certain romanticism and creativity into her rejection of the conventional. There is a distinct glamour to her low-key wedding, to which she wears a linen dress and a pair of flat sandals, only bothering to notify her parents after the fact. And it is the same creative flair that she uses to get herself out of serious trouble — in one scene, Sanmao is able to save José from drowning in a swamp by crafting a makeshift life raft out of a spare tire while stripping her own clothing and fending off a group of licentious men. That flair also enables her to renovate the couple’s “shabby” house in the unfashionable cemetery district into a stylish villa admired by locals and expats alike.

Social media influencer avant la lettre?

As the New York Times observed in an obituary, Sanmao’s collection retains the ability to resonate with the present-day reader in part because her writing style, which blends a romanticized solo traveler persona with brutal self-honesty, has much in common with what one might find on social media. While Sanmao may be both glamorous and intrepid, she is also relatable. She is candid about the loneliness that desert life brings and her doubts over her decision to move, and even admits that her relationship with José is based on a certain comfort rather than passion.

And it is perhaps this unusual combination of traits that inspires the reader most. Even when Sanmao talks about the inescapable loneliness of traveling alone, her knack for dodging real trouble gives readers the impression that such solo sojourns are possible. Sanmao is like us, but better. She represents what we could be.

Yet while her confessional style may feel particularly present-day, a point Sharlene Teo notes in the new English edition’s preface, in other ways, her descriptions of local Sahrawi life leap out as jarringly problematic artifacts. While Sanmao’s relative progressiveness constitutes a key part of her wanderlust persona, it does not extend far enough to prevent readers from wincing at some of her descriptions of the local Sahrawi population. Remarks about the hygiene practices of certain Sahrawi characters spark a particular discomfort, something translator Mike Fu notes he had to grapple with at the end of the book before opting to leave in, out of fidelity to the original.

Similarly, while the reader is constantly aware of the book’s physical setting, with the oddities of Sahara life driving the plot of nearly every story, the political dynamics of colonial El Aaiún rarely get exclusive attention. It is only in the book’s closing chapters that Sanmao opts to shift explicit focus to the area’s racial and political tensions. This is something that may frustrate the more politically inclined reader accustomed to the political musings scattered throughout the works of contemporary travel writers like Paul Theroux. It also feels like a missed opportunity to fully capitalize on the uniqueness of Sanmao’s position as a young Chinese-born Spanish-speaking woman in the Western Sahara with a large indigenous population on the brink of full Moroccan takeover. Instead, Sanmao opts to give primacy to her often-humorous cross-cultural interactions with locals, the Spanish officials, and, most endearingly, José.

Almost every review of this book is likely to note that Sanmao’s short life was also heavily punctuated with tragedy. José died in a diving accident just a few years after the book’s first publication, marking the second time Sanmao lost a partner (her first fiancé, a teacher from Germany, died of a heart attack several years earlier). Subsequently, Sanmao took her own life in 1991, 10 years after her return to Taiwan as a successful writer. While she achieved fame and success within her lifetime, it is also worth asking what role such tragedy has played in fueling an enduring fascination with both her persona and her writing. In any case, readers are left with a heightened sense of her deep love for exploration and human connection.

Sanmao’s vivid descriptions of Sahara life, with its assortment of local personalities and unexpected twists, make an engaging read, but an undeniable part of the book’s enduring appeal is Sanmao herself. Stories of the Sahara offers a glimpse into not only an underreported time and place, but also the making of a cultural icon.

Stories of the Sahara, translated by Mike Fu and published by Bloomsbury, is available on Amazon.