‘One Thousand Families’: Intimate portraits of Chinese lives during coronavirus

The “One Thousand Families” series, featuring portraits of Chinese families, tries to capture a sense of how people are faring during the COVID-19 epidemic. In the eyes of the masked subjects, we see boredom, resilience, anxiety, love, anger, and humor.

“We stay in 24 hours a day,” says Luō Dàwèi 罗大卫 via telephone from his home in Tianjin. “You can’t go anywhere, you can’t even order things, as no one is delivering. The best word to describe life right now is imprisonment.”

Luo has, like many of his compatriots, endured a sobering Chinese New Year. Despite living more than a thousand kilometers from the COVID-19 epicenter in Wuhan, he complains, “My district is the most seriously affected in the Tianjin Municipality.”

But being stuck at home doesn’t mean he hasn’t kept busy.

Since 2017, Luo has run Fēngmiàn 风面, an innovative online contemporary photography platform that boasts more than 63,000 online subscribers. The platform is currently hosting one of its most impactful projects to date, called “One Thousand Families,” featuring portraits of Chinese families affected — either directly or indirectly — by the coronavirus.

The idea for One Thousand Families (“1000个家庭” gè jiātíng) came from photographer Wú Guóyǒng 吴国勇, whose career Fengmian helped launch. His photographic series No Place, To Place, about the environmental fallout of China’s share-bike boom and bust, has been exhibited globally, including at major festivals in China and galleries in Russia, France, and Cambodia.

Wu, who currently lives in Shenzhen, hails from Hubei Province, where COVID-19 emerged in late 2019. Of the 64,000-plus confirmed cases so far, more than 80 percent are from Hubei.

“I was at home in Xiangyang (in Hubei) for (Chinese) New Year when the crisis really began,” Wu says. “I’d planned to stay some weeks but my relatives urged me to leave before it was too late. I drove back to Shenzhen and it rained the whole way, dousing all the New Year’s firecrackers. It was a somber trip. When we got back to Shenzhen, the local public security bureau told us we had to stay at home. Because I’m from Hubei, they’ve been checking up on me daily.”

It was while quarantined at home that Wu’s creative gears started turning.

“I began to think about the national mood, which is awful,” he says. “The news is terrifying. Everyone is stuck at home, frustrated. Then I thought: maybe we could all do something creative together. As it is traditional to take a family portrait over Chinese New Year, I wondered if everyone could use photography to document the New Year of the virus. But I needed to figure out how to reach a lot of people.”

Wu got in touch with Luo Dawei.

“Wu is an artist sensitive to the human struggle,” Luo says. “He told me his idea, which I meditated on for a day. I decided to work with him. We advertised on Fengmian to all our followers asking them to photograph how their New Year was playing out in either official or unofficial quarantine.”

The feedback they got exceeded their expectations.

Wu explains: “We launched on January 30 and we quickly started to receive a lot of photos. We picked the best ones and posted them online.” This caught the attention of China’s largest internet company: Tencent shared the project on its platform. More than 16,000 people have contributed to the collection so far, Wu says.

“We were really touched by the response,” says Luo. “And we began to think about an exhibition, when this crisis is over. We decided we should get our artist friends to get involved as well. We reached out to them and they responded, too, providing us with nuanced, critical, or even abstract images. They took the project to the next level.”

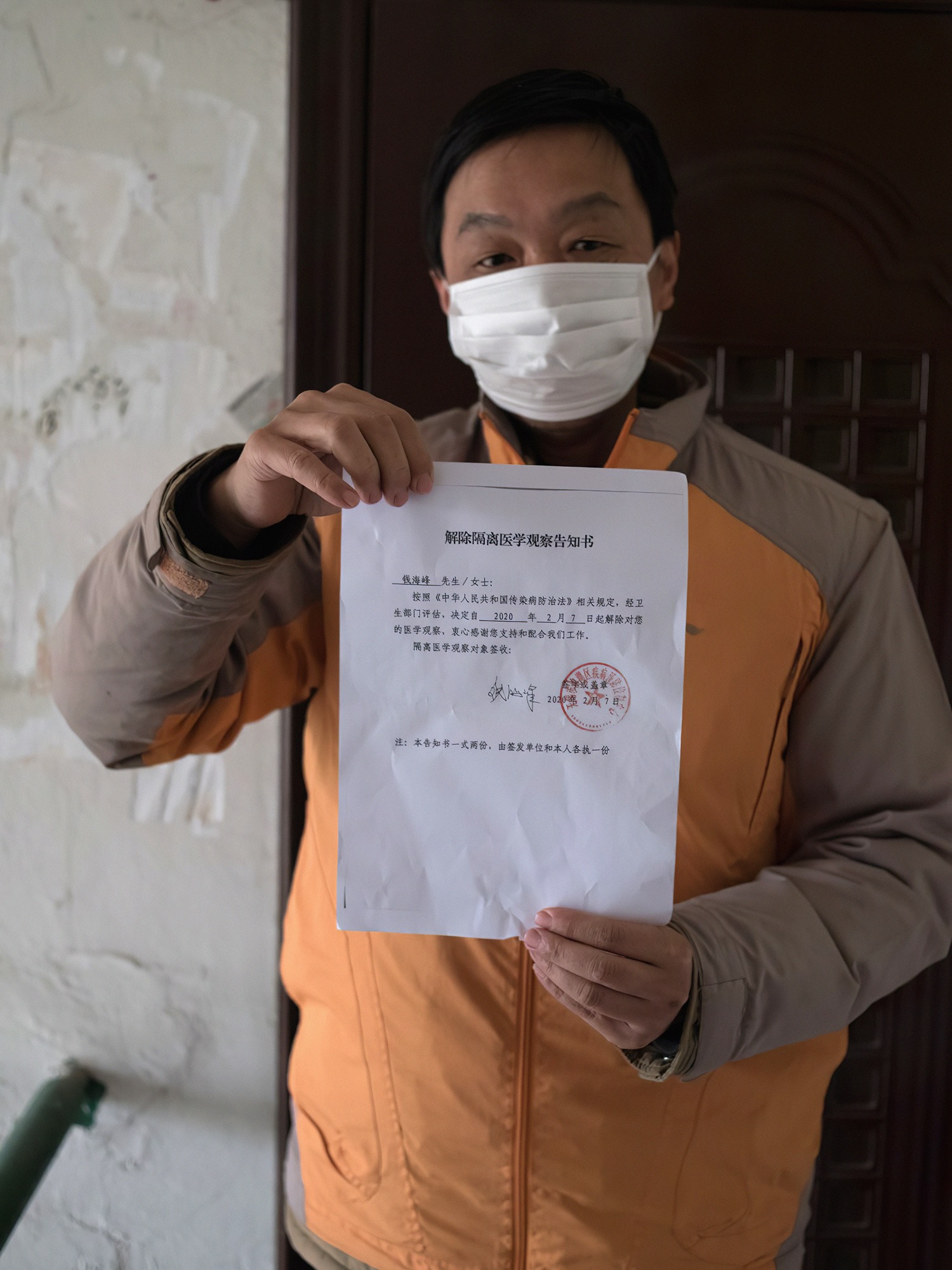

Among those who have contributed include Lǚ Tíngchuān 吕廷川, Zhāng Xiǎowǔ 张晓武, Wáng Xiàngyáng 王向阳, Liú Shūtóng 刘书彤, Lǐ Lín 李林, Luō Jīnqiàn 罗金倩, Qián Hǎifēng 钱海峰, and Coca Dai (戴建勇 Dài Jiànyǒng).

The diversity of images is quite extraordinary, given the topic. Both amateur and professional photographers have endeavored to capture the boredom, isolation, worry, and camaraderie that they’re experiencing.

As the audience, we see relatives peering over masks towards the camera lens, their eyes emitting a catalogue of emotions ranging from anxiety to melancholy to stoicism and resolve. We bear witness to intimate moments of caring as well as humor as people make light of the absurdity of their situation.

While some photographers employ the camera to criticize authorities, others try to capture the tender, hidden aspects of their lives, currently lived under the world’s largest-ever quarantine.

“You know jiā (家) means family and home in Chinese,” Wu explains. “Chinese New Year is the one time both jia’s come together as one. This virus has struck at the heart of our culture. We wanted to show what that meant from the inside out.”

Below are a selection of photos from the series — all captions were originally written by the person who sent the original photography, which we have translated from Chinese.

Wu Guoyong, Xiangyang City, Hubei Province. This portrait was taken at the home of my father-in-law during New Year’s Eve dinner on January 24, 2020. That day Wuhan announced that it will close. Although Xiangyang had not officially confirmed any cases, there were already many suspected cases. During dinner, my mother-in-law said that you should hurry back to Shenzhen. It took only 16 hours and 1,300 kilometers to get home on New Year’s Day. I then went into self-isolation at home, where I took a daily temperature report.

Liu Weiguang, Pingdu City, Shandong Province, January 30, 2020. Chinese New Year is always an exciting event. My father had to go to town to buy fireworks for his grandson. He bought a pair of red lanterns and a plate of 10,000 firecrackers. Because of the epidemic he wore a mask. I took his picture beside the character fú (福), meaning fortunate.

Li Lin, Dongying City, Shandong Province. February 9, 2020 should be the first day of school. But because of the virus outbreak, classes are being taught online. This is my daughter studying at home via the school’s live broadcast. Our city has no reported cases.

Zhang Xiaowu, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province. On my way back to Hangzhou for New Year, I was aware of the virus outbreak but I did not expect it to be so serious that I would have to isolate myself in a house. I’m experiencing the disappearance of an individual’s life. It’s so real and sad. I took a picture of myself under a weak light. I was struggling to see direction, to see where the light comes from. I digest a huge amount of information every day in order to try and understand the truth, but in this situation, I cannot see the truth. I suppose I’m asking if some change will come of all this.

Wang Meng, Yiwu, Zhejiang Province. My grandparents came to Yiwu to celebrate the New Year. This is our family portrait. We put on our best clothes to wish “Wuhan Keep Going.”

Zhao Youzhu, Inner Mongolia, February 12, 2020. During the extended Chinese New Year holiday in 2020, everyone has been self-isolated at home. For more than 10 days, the children in our household set up a tent in the living room, filled it with supplies, and went “indoor camping.” This image seems to capture what we’re going through as a people. Worlds within worlds within worlds.

Qian Haifeng, Wuxi, Jiangsu Province, February 7, 2020. During Spring Festival, like most years, I took 10 trains across China to photograph migrant workers, including in Hubei, the birthplace of this epidemic. According to official regulations, when I got home I had to be isolated for two weeks. I wan’t very worried. I have been traveling China for the better part of a decade and have been in worse trouble. I already beat cancer. The only thing that disturbed me is that I live with my parents and thus I had to isolate myself in my room as much as possible. During those lonely days, the community would send someone to deliver the food I needed and place it outside the door. The local clinic observed my medical progress, and when I completed my 14 days, I picked up the book documenting my period of isolated medical observation. I asked the community staff to take a photo, saying, “During this extraordinary period, let’s leave a memorial.”

Jieda Xihuan (internet alias). I can’t go anywhere. I scan Weibo on the internet, read what everyone is saying, but I’m not sure what to say. So I made this image to express what it feels like to live through this crisis.

Shi Tou, Qingzhou, Shandong Province, January 6, 2020.

Ye Qiang, Xiangyang City, Hubei Province, February 11, 2020. It has been 20 days since the city was closed. Although we are not in the center of the epidemic, we consciously do not go outside at all. Occasionally we can take in some fresh air in the yard and peer out on the world, our gated community.

Zhu Wenxia, Luzhou City, Shandong Province, January 30, 2020. My wife and I offering New Year’s wishes: “Wuhan Peaceful, China Peaceful.”

Luo Jinqian, Liuzhou, Guangxi Autonomous Region, January 31, 2020. New Year’s Day is the birthday of my mother-in-law, who turned 85. Because of the spread of the new coronavirus this year we dare not go out and order a cake. We found a small box of birthday candles, which we inserted into mandarins and then made this picture to try and cheer everyone up.

Zhu Weibin, Yuan’an County, Hubei Province, February 12, 2020. New Year’s Eve dinner was uneasy. I received the message at 10 o’clock in the evening that Xiaogan was locked down. I persuaded my parents to go back with me to Yuan’an. When the New Year’s bell rang, we crossed the Xiaogan North Expressway. We got in at 4:30 in the morning. After 14 days of self-isolation we were getting restless. I knew that they wanted to go out, so on February 12, 2020, my mother’s 79th birthday, with no cake, flowers, or gifts, I took this family portrait in my own courtyard.

Coca Dai, Shanghai. The government closed the city down for 13 days. We were trapped at home every day and couldn’t go out. My son Dai Zhu had to wear a mask when he was let out to play. He said he was going to scare the virus. Behind is his mother, Zhu Fengjua (Judy Zhu).

Li Yonghong, Loudi, Hunan Province, January 4, 2020. During the Spring Festival, I returned from Shenzhen to Hunan to celebrate the New Year, and I was catching up with friends when the virus outbreak became public. Our family is trapped at home and we dare not go anywhere. When the weather is good we go for a breather at the top of my building. You can see nobody bothers with their fancy New Year clothes. We’re seen in the Year of the Rat in our pajamas.

Huang Xiaoxin, Shenzhen, February 1, 2020. When I returned to Shenzhen from frosty Tibet a few years ago, I was happy to be in the city. I never expected things would turn out like this. The Wuhan coronavirus has swept through the country like a tsunami and impacted our lives directly. I now miss the mountains and rivers and the air of the plateau.

Tang Ling. With the virus in the air, father and son stay at home during Spring Festival and play chess.

Guo Zhihua, Binzhou City, Shandong Province, February 5, 2020. Miss Liu is practicing yoga at home to stay healthy during the coronavirus epidemic.

Tang Tang. The cold wind outside the window blew, my grandma gradually fell asleep, covering her hands. Our whole family is trapped together over Chinese New Year but I sense her loneliness. The elderly are the worst affected.

Shi Youzi. This was the first time I went home for Spring Festival in 10 years. Then the epidemic made Hubei a severely affected area. The first thing I do when I wake up every day is to quickly read the news to see the data — the sick people, the doctors who are treating them, the support from all sides — and try to measure the progress of the national treatment program.

Anonymous. On February 7, 2020, Dr. Lǐ Wénliàng 李文亮, who first issued a warning about the coronavirus but was silenced, died. This angered people across the country. These girls are bravely saying, “There’s no way we don’t understand.”

Wang Feng, January 26, 2020. Spring Festival is a time for a family portrait but this year, due to the epidemic, my grandfather did not make it. This picture spells my sense of regret.

Wang Xin, Chongqing. Our family came to my grandmother’s house from Wuhan, the birthplace of the epidemic, one day before the city was closed. With the intensification of the epidemic, we were ordered to say in for 14 days. The paper you can see under the window was the government’s quarantine notice. Every day, people from the town come to take our temperature and disinfect the area.

For more photos, see this WeChat post by Wu Guoyong, which has a QR code at the bottom for the “One Thousand Families” WeChat page.