The Communist Youth League thought it was creating patriotic idols. Instead, it started a conversation about women’s rights

The Communist Youth League thought it was creating patriotic idols. Instead, it started a conversation about women’s rights

At this point, it’s no secret that the Communist Youth League of China (CYLC), the Chinese Communist Party’s division for young people, knows the language of the internet. Since it discovered Weibo, where it now boasts over 12.7 million followers, the association has dived into several subcultures and created a variety of content that it thinks is entertaining and relatable to its digitally literate audience. (It thinks being the operative words; witness the Karl Marx anime and patriotic rap songs.)

The CYLC’s latest effort, however, has been a monumental failure, a gaffe that ranks as one of its worst projects to date — which is saying something, considering the heretofore-mentioned patriotic rap songs.

On February 17, the Youth League tried to hype a pair of virtual influencers that it had been working on, named Jiāngshānjiāo 江山娇 and Hóngqímàn 红旗漫. The characters were introduced as the league’s “new friends” in a Weibo post that featured a poem (in Chinese) by Mao Zedong, which is where the idols’ names derives from. The league unveiled a teaser image of Jiangshanjiao and her brother, with the words “New Vtubers are coming soon” over their silhouettes.

Things went downhill right away. In a matter of hours, thousands of negative comments poured into the league’s Weibo page, admonishing it for its attempt to personify itself for political purposes. Many people excoriated the league for the insensitive timing of the announcement, arguing that the government should be devoting its efforts to addressing the ongoing COVID-19 outbreak rather than launching a new propaganda initiative aimed at stirring nationalistic sentiment.

“Are you out of your mind? Combining patriotism and entertainment is the worst idea ever. I paid my membership fees for years hoping they would be used on building my country. Now you are telling me this is what you came up with?” a Weibo user wrote (in Chinese).

Many also pointed out the double standards in the league’s co-opting of the uniquely hardcore culture of idol fandom China. Before the creation of Jiangshanjiao, the league — on more than one occasion — has lambasted passionate fans of celebrities for their tendency to go overboard with their fandom. In particular, the league disdains “little fresh meat,” young good-looking male entertainers who are seen as posing a challenge to a set of hyper-masculine values endorsed by Chinese officials. The league instead wants to promote its own publicly-approved patriotic celebrities.

It’s funny that the league has never been friendly to fans of pop idols, who are mostly tech-savvy millennials and their younger “Gen Z” counterparts, but is now trying to court their attention.

“You called our culture ‘toxic’ before and now you are trying to convince us to direct relentless, unquestioning positivity toward a digital subject. We know what you are doing here. We are not brainless fools,” an angry fangirl wrote (in Chinese).

Shortly after the league’s post, Jiangshanjiao sent her first message through her official Weibo account, like a corporate mascot trying to connect with customers. Seemingly aware of the critical feedback, Jiangshanjiao’s account remained hopeful that her haters would ease up in the future. “My brother and I were so moved by the support we received so far. We will make our best effort to make everyone happy,” the account wrote. “But I understand that it’s hard to make everyone pleased. I want to ask my fans to call a truce with my haters.”

At this point, almost everyone on Weibo was fed up with this cringeworthy government-orchestrated social media campaign. With few people coming to the league’s defense, Jiangshanjiao’s Weibo account became flooded with harsh criticism. “Get out of my face,” an annoyed Weibo user commented (in Chinese).

When it became apparent that the Weibosphere wasn’t going to relent the league deleted the teaser and took down the official Weibo account of the idols. Meanwhile, on video streaming platform Bilibili, a new channel set up by the league for the characters was scrapped without any explanation.

The sudden removal of the project’s entire online presence didn’t entirely calm the storm, as internet users who screencapped the images continued voicing their displeasure. Eventually, the complaints snowballed into a major Weibo trend, inspiring a few hashtags related to the event, such as #江山娇与红旗漫死了# (#Jiangshanjiao and Hongqiman are dead).

Alongside a string of recent news stories about female workers being mistreated or downplayed in the fight against the coronavirus outbreak, the Jiangshanjiao and Hongqiman campaign struck a nerve with women on the internet, who used the virtual figures as an outlet to vent their frustrations about gender inequality in China.

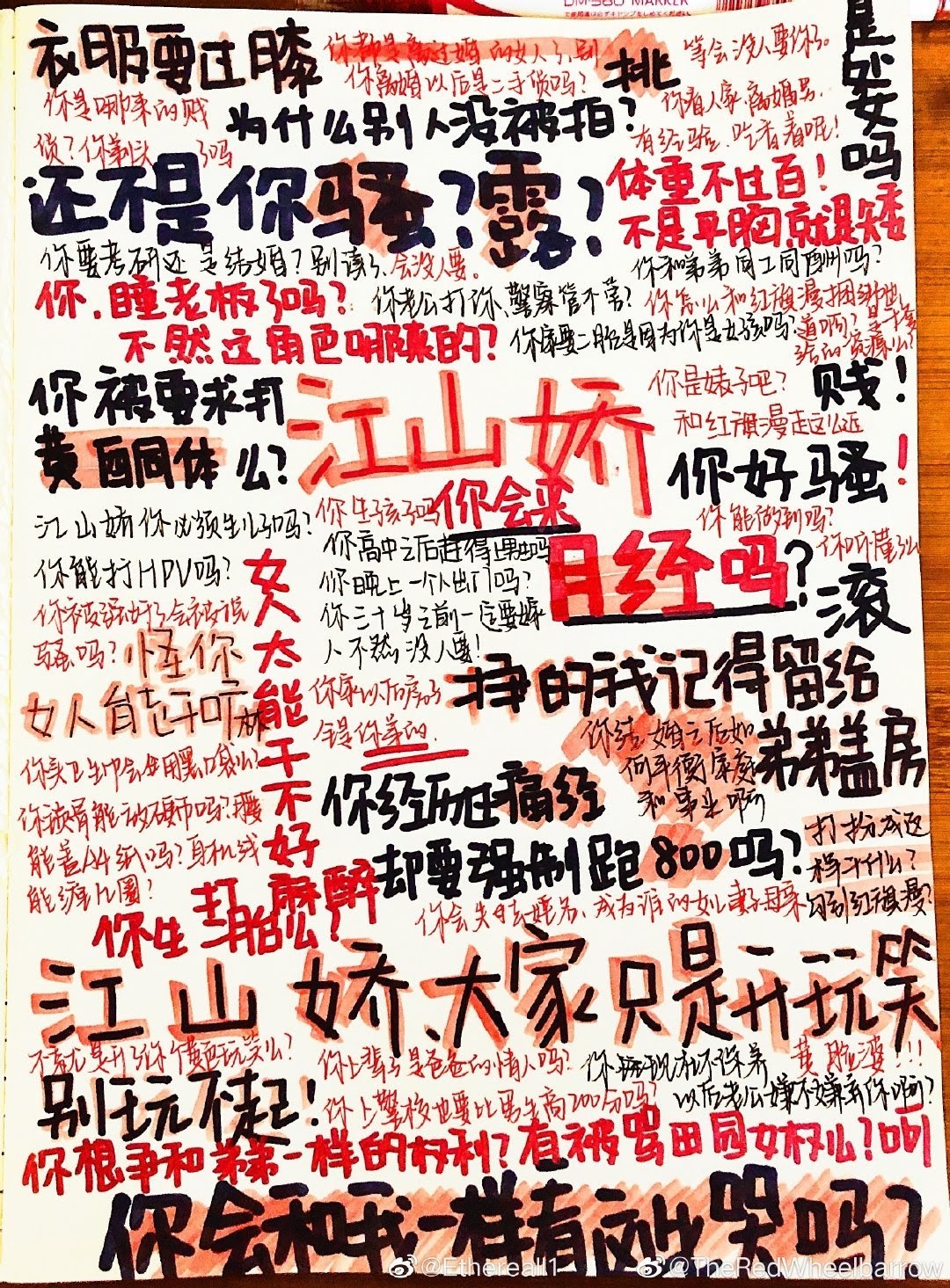

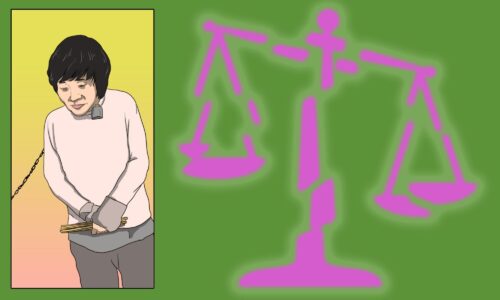

In a series of since-deleted Weibo posts, Weibo user @为什么它永无止境 (wéishímetāyǒngwúzhǐjìng, “Why it’s endless”), an outspoken advocate of women’s rights, directed a series of questions at Jiangshanjiao, asking if she had to deal with the many challenges faced by Chinese women. In reference to the systematic mishandling of sexual misconduct cases on Chinese campuses, the Weibo user wrote (in Chinese), “Jiangshanjiao, have you ever been forced to drop out after being sexually assaulted?” Following her feminist lead, thousands of internet users weighed in with questions such as, “Jiangshanjiao, are you comfortable with walking home alone at night?” “Jiangshaojiao, do you need to get married before you hit 30?” and “Jiangshaojiao, are you saving up to buy a house for your brother?”

It didn’t take long before Weibo decided to censor the whole conversation. But in the 12 hours it was alive, the original post garnered more than 8,000 replies and nearly 310,000 likes. On February 18, @为什么它永无止境 made another post (in Chinese) explaining her intentions. “I shot questions at Jiangshanjiao because I wanted to find out to what extent a virtual idol representing the nation understood the plight of women,” the feminist wrote. “My questions have led to a meaningful discourse that doesn’t belong to me anymore. It has become a symbol that prompted other people to continue questioning. If you don’t ask, you’ll never have the answer.”