Stay abroad, or return to China? One Chinese student grapples with the decision

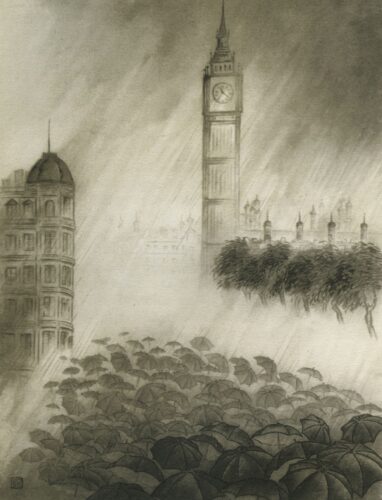

Illustration by Derek Zheng

The UK’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic has left much to be desired, but for Chinese nationals with the option, is returning to China during this time really all that wiser?

On March 13, in an interview with Sky News, England’s chief science adviser Sir Patrick Vallance said that 60% of the population “will need to be infected” in order to reach “herd immunity.” This now infamous “herd immunity” theory was, at that time, part of the government’s strategy to combat the coronavirus. Following this announcement, panic and fear spread among the Chinese diaspora in the UK.

The next day, when I woke up, my WeChat was filled with links to a Chinese article titled, “British government admits it will let millions get infected in order to build herd immunity.” It didn’t take long before my mom, who lives in northeast China, got the news. She called me, cried, and begged me to come back as soon as possible. My dad asked if the British government had gone insane.

Suddenly, I realized I had to choose between staying in the UK, where according to the “herd immunity” theory, two-thirds of the population was expected to be infected, and returning to my home country, where the leadership was ready to declare victory as new domestic cases of COVID-19 have been reduced to nearly zero after an aggressive two-month battle. The answer seemed easy: If home is safer, go home.

But for Chinese students who study abroad — and many of us do so not just for the education, but also to experience the free and open society promised by liberal democracies — to stay or to go is not simply a question of which country is safer. It is a question about which political system is more capable and trustworthy. I struggled with my decision, because nothing else has quite tested my faith in “the Western system.”

I’ve been following the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan since Day 1, and I’ve encountered too many tragic stories brought about by the Chinese Communist Party’s aggressive Mao-style anti-virus campaign. The complete lockdown of cities has been accompanied by an introduction of emergency regulations that have enabled an unprecedented extension of state power into personal lives. These measures are tough, crude, and often brutal. Those most vulnerable — the poor, the disabled, the diseased, and the elderly — have been the hardest hit. The implementation of these top-down policies on a grassroots level has been extreme, and accompanied by chaos, confusion, and violence. As Chinese historian Luo Xin 罗新 said in a podcast, the sudden lockdown and the authority’s unpreparedness for it may have caused more harm than the virus itself.

Before Europe learned of the severity of the virus, such an aggressive strategy was generally assumed to be possible only in China. Only the Chinese Communist Party, powered by its long tradition of campaign-style governance, had the capacity to mobilize and execute this strategy. Only the CCP, with regime stability as its No. 1 priority, would have been willing to contain the virus at all costs.

So what do we make of European countries, from Italy to Germany, beginning to adopt strategies similar to China’s, most notably the lockdown of cities? Is it possible that China’s strategy, backed by facts and science, is needed to save lives?

In the past week, I have found myself confused and upset by the suggestion that the Chinese authoritarian system is inherently superior in handling crises. To borrow the words of a friend of mine: China may have gotten a D in this exam, but the West’s response isn’t good enough for even an F. It’s not as if authoritarianism is the root cause of China’s success. Let’s remember the words of Wuhan University professor Feng Tianyu (as quoted by Wuhan writer Fāng Fāng 方方), who said: “When it comes to expressing thanks, never invert the relationship of the people to their rulers.” And as Ian Johnson writes, “There’s nothing authoritarian about checking temperatures at airports, enforcing social distancing or offering free medical care to anyone with Covid-19.”

Now, following the outbreak in day whatever-this-is, I’m annoyed by how the West seems to have copied China’s worst measures, but ignored some of its successful ones (like ubiquitous temperature checks). Western countries that have presented an alternative path, such as the UK, have failed. What is even more disturbing is that alternatives have not been nearly as liberal, democratic, or humane as I would have expected. Human lives are reduced to statistics, and human suffering has become a necessary cost for societies to absorb.

The British government’s exceptionally slow response to COVID-19 reminded me of Chinese authorities’ “Everything is under control” talk during the early days of the Wuhan outbreak. Boris Johnson’s take-it-on-the-chin tone when he told people to prepare for “losing their loved ones” echoes Xi’s “We will win this People’s War against coronavirus at all costs,” even when the cost is the lives of those trapped in Hubei Province. Why hasn’t the enlightened West been able to produce a strategy more enlightened than “wait for herd immunity”?

The weekend following Johnson’s briefing on March 13 was a chaotic and confusing time for many Chinese students in the UK. Plane ticket prices soared as much as fourfold, and, “Are you going back?” became the most frequently asked question among us. As more and more people around me began to pack and leave, I grew more anxious in my indecisiveness.

Is it still reasonable to trust the British government’s ability, or indeed its willingness, to control the spread of the virus? Is there any possibility that the small boring English town where I live will become the next Wuhan, and Britain the next Italy? When some Chinese students in our WeChat group sarcastically commented, “What happened to human rights” or “Why can’t they just learn from China,” I couldn’t help but ask myself: By choosing to go back, would I be choosing China’s authoritarian system over democracy?

In the end, I’ve decided to stay.

I know that it’s possible I’ll spend the next few months in my room, and as the situation worsens, the government will take measures to restrict people’s freedom to travel or gather. Still, I have chosen to stay because I know that the UK police would not break down my door, smash up places of recreation, or march people out for public shame; my pets would not be left to fend for themselves if I were physically removed to a quarantine center, my neighbors would not report me just for entertaining foreigners, and my door would not be fitted with a motion sensor; I would not be condemned online as someone shamelessly bringing the virus back to her home country.

I want to choose to not go outside, to maintain social distance, and have my temperature checked, as a responsible citizen fulfilling her civic obligation amid a global pandemic — instead of facing the stigma of being a potential virus carrier by both the state and my fellow citizens. While I have been surprised by how terrible a job many Western countries are doing with this pandemic, what compels me to stay is not because a liberal democracy can better handle a crisis than China — because it can’t — but because the West — though it is now repeating some of China’s aggressive measures — is still able to protect some level of basic human rights. What I want, by staying in the UK, is to maintain that shred of respect and dignity that individuals are endowed with — that little something I hope we don’t forget about as we brace for worse days ahead.