The Americans who fled China due to coronavirus, only to flee back

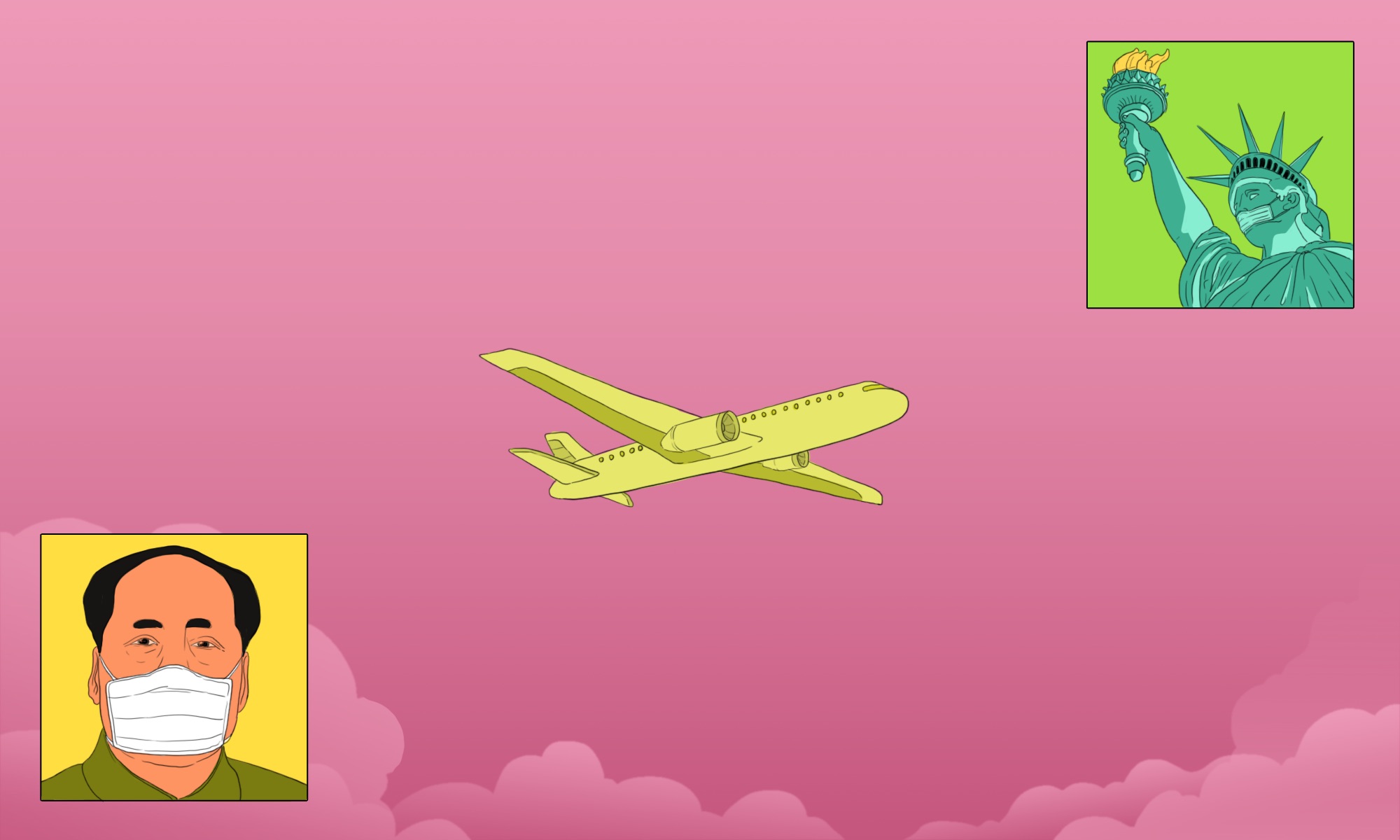

Illustration by Derek Zheng

On February 2, the U.S. Department of State issued a Level 4 travel advisory urging Americans living in China to “attempt to depart by commercial means,” and that anyone staying should take precautionary measures such as “stocking up on food.” Two days earlier, the U.S. began organizing emergency flights out of Wuhan for American citizens, and officially ordered the departure of “all family members of U.S. personnel [across the Beijing embassy and consulates general] under age 21 from China.”

It also issued a ban on all foreign nationals who had visited China in the last 14 days from entering, and imposed, at least on paper, a mandatory 14-day quarantine on American travelers who had been to Hubei Province. For many Americans, the announcement led to panicked ticket-buying.

But when the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19 began its unchecked spread in the U.S. — and before China closed its borders to foreigners on March 28 — many of those same Americans found themselves going through the familiar hurried, chaotic process of moving: only this time, back to China.

For history teacher Alexander Lee, the State Department’s February 2 travel advisory was the impetus to book a ticket from Guangzhou to the U.S. “There is a Vietnam War era period film called The Sand Pebbles — the moral of the story is it’s a good idea to leave when your government tells you to do so,” he said, adding that he had planned to bring over his Chinese partner and children at a later date.

“I regret having left,” he now says.

For Shanghai residents Jorge Castellanos and Kimberly Wong, the eerie quiet of the city in late January had them anxious about the future. Both noted that even without a mandatory lockdown, streets were already empty and restaurants and bars were voluntarily closing.

“Because everything was so unprecedented, I was nervous as to how far measures would go. I decided to go home before flights were cancelled,” said Castellanos, who runs a local comedy group. “It was tense because the entire city was unaware of what was going to happen the next day, let alone the weeks or months following.”

Wong, a designer, had been struggling with the impact on her business. “I had to make a choice between peace of mind over my company. I had pretty much been living in isolation for four weeks at that point, and the thought of not being able to go outside scared me. I wanted to be with my family.”

All three returned to an America that was oblivious to the looming threat of COVID-19. The country was much less prepared than China, with Trump administration officials dragging their feet on a response even as the virus was beginning to ravage Wuhan.

Castellanos, who flew in on February 1, doesn’t remember any safety measures in San Francisco, where he touched down. “There were no temperature checks or anything… At the time, it was not really expected to self-quarantine, but I did avoid going out, just in case. Really, it was because [friends and family] were a bit nervous at the fact that I had just returned from China.”

Two weeks later, things in the U.S. had begun to change, but only a little.

“I was told by a CDC worker that it was optional for me to quarantine,” said Lee, who arrived in New York on February 17. He had already planned to distance himself, renting a cabin upstate to spend two weeks. He sent his details into the CDC; local health officials showed up three days later.

“I had to report, after an initial face-to-face meeting, my temperature to them once a day,” Lee said. “They provided in a large Ziploc bag a thermometer, latex gloves, surgical masks, Clorox wipes, Purell hand sanitizer, and Kleenex. I was the first person to quarantine in the county.”

But as the days passed, Lee said it was clear that people in the U.S. weren’t taking COVID-19 as seriously as the Chinese. He began contemplating a return to China. The deciding factor, for him, was seeing the explosion of cases coming out of Seattle. Three days after his self-imposed quarantine ended, he bought a standby ticket to go back to Guangzhou on March 17, despite protests from his mother.

“My mother was heartbroken and ended every conversation saying that she wished I would not go back,” he said. “She could not understand that I felt it would be safer and that I wanted to be reunited with family.”

Wong, who had gone to nearby New Jersey, recalled getting very little guidance upon landing. “[The CDC at the airport] took my temperature, but then didn’t give me anything else beyond that. An entire week later, I was called at home to ask if I had been taking my temperature twice a day. Uhm, no?

“They said they would email me more information but I never got anything. I found [the information] myself on the CDC website. They contacted again after 14 days and I was fine. I never took my temperature.”

Processing it all was like “being smacked in the head with a baseball bat,” Wong said. “I cancelled on going into Manhattan to attend a podcast conference. I am super lucky I didn’t go…one of the speakers there tested positive for COVID-19.”

She made the final decision with her family on March 18 to return to China, and was out on a flight the very next day.

Wong, Lee, and Castellanos found themselves returning to a very different environment. There were several rounds of temperature checks upon entry in China, with airport employees and volunteers in full hazmat suits constantly disinfecting. All three returned to mandatory home quarantines, in which monitors were installed on their doors and a community manager checked in to record their temperatures twice a day.

But despite the long hours and general hassle, all three preferred this to what they had encountered in the U.S.

“I was pleasantly surprised at how nice the staff were and how accommodating they were to us,” Castellanos said. “I saw a message that said, ‘People need to understand this isn’t a punishment but rather done to take care of you,’ which was true and was evident in how things were done.”

Said Wong: “Every time I think back to the moment that I saw volunteers at the airport in hazmat suits, I tear up. They were so proud to put themselves potentially in danger to help everyone. I sent them a message to thank them for their service the other day, and the response was this: ‘Thank You! This is something we should do, and thank you very much for your understanding and support.’”